CANTO XXXII

COULD I command rough rhimes and hoarse, to suit

That hole of sorrow, o'er which ev'ry rock

His firm abutment rears, then might the vein

Of fancy rise full springing: but not mine

Such measures, and with falt'ring awe I touch

The mighty theme; for to describe the depth

Of all the universe, is no emprize

To jest with, and demands a tongue not us'd

To infant babbling. But let them assist

My song, the tuneful maidens, by whose aid

Amphion wall'd in Thebes, so with the truth

My speech shall best accord. Oh ill-starr'd folk,

Beyond all others wretched! who abide

In such a mansion, as scarce thought finds words

To speak of, better had ye here on earth

Been flocks or mountain goats. As down we stood

In the dark pit beneath the giants' feet,

But lower far than they, and I did gaze

Still on the lofty battlement, a voice

Bespoke me thus: "Look how thou walkest. Take

Good heed, thy soles do tread not on the heads

Of thy poor brethren." Thereupon I turn'd,

And saw before and underneath my feet

A lake, whose frozen surface liker seem'd

To glass than water. Not so thick a veil

In winter e'er hath Austrian Danube spread

O'er his still course, nor Tanais far remote

Under the chilling sky. Roll'd o'er that mass

Had Tabernich or Pietrapana fall'n,

Not e'en its rim had creak'd. As peeps the frog

Croaking above the wave, what time in dreams

The village gleaner oft pursues her toil,

So, to where modest shame appears, thus low

Blue pinch'd and shrin'd in ice the spirits stood,

Moving their teeth in shrill note like the stork.

His face each downward held; their mouth the cold,

Their eyes express'd the dolour of their heart.

A space I look'd around, then at my feet

Saw two so strictly join'd, that of their head

The very hairs were mingled. "Tell me ye,

Whose bosoms thus together press," said I,

"Who are ye?" At that sound their necks they bent,

And when their looks were lifted up to me,

Straightway their eyes, before all moist within,

Distill'd upon their lips, and the frost bound

The tears betwixt those orbs and held them there.

Plank unto plank hath never cramp clos'd up

So stoutly. Whence like two enraged goats

They clash'd together; them such fury seiz'd.

And one, from whom the cold both ears had reft,

Exclaim'd, still looking downward: "Why on us

Dost speculate so long? If thou wouldst know

Who are these two, the valley, whence his wave

Bisenzio slopes, did for its master own

Their sire Alberto, and next him themselves.

They from one body issued; and throughout

Caina thou mayst search, nor find a shade

More worthy in congealment to be fix'd,

Not him, whose breast and shadow Arthur's land

At that one blow dissever'd, not Focaccia,

No not this spirit, whose o'erjutting head

Obstructs my onward view: he bore the name

Of Mascheroni: Tuscan if thou be,

Well knowest who he was: and to cut short

All further question, in my form behold

What once was Camiccione. I await

Carlino here my kinsman, whose deep guilt

Shall wash out mine." A thousand visages

Then mark'd I, which the keen and eager cold

Had shap'd into a doggish grin; whence creeps

A shiv'ring horror o'er me, at the thought

Of those frore shallows. While we journey'd on

Toward the middle, at whose point unites

All heavy substance, and I trembling went

Through that eternal chillness, I know not

If will it were or destiny, or chance,

But, passing 'midst the heads, my foot did strike

With violent blow against the face of one.

"Wherefore dost bruise me?" weeping, he exclaim'd,

"Unless thy errand be some fresh revenge

For Montaperto, wherefore troublest me?"

I thus: "Instructor, now await me here,

That I through him may rid me of my doubt.

Thenceforth what haste thou wilt." The teacher paus'd,

And to that shade I spake, who bitterly

Still curs'd me in his wrath. "What art thou, speak,

That railest thus on others?" He replied:

"Now who art thou, that smiting others' cheeks

Through Antenora roamest, with such force

As were past suff'rance, wert thou living still?"

"And I am living, to thy joy perchance,"

Was my reply, "if fame be dear to thee,

That with the rest I may thy name enrol."

"The contrary of what I covet most,"

Said he, "thou tender'st: hence; nor vex me more.

Ill knowest thou to flatter in this vale."

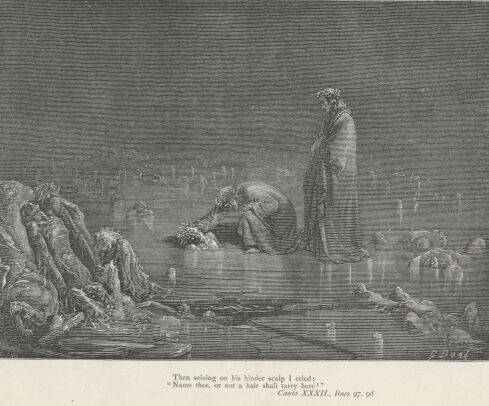

Then seizing on his hinder scalp, I cried:

"Name thee, or not a hair shall tarry here."

"Rend all away," he answer'd, "yet for that

I will not tell nor show thee who I am,

Though at my head thou pluck a thousand times."

Now I had grasp'd his tresses, and stript off

More than one tuft, he barking, with his eyes

Drawn in and downward, when another cried,

"What ails thee, Bocca? Sound not loud enough

Thy chatt'ring teeth, but thou must bark outright?

"What devil wrings thee?"—"Now," said I, "be dumb,

Accursed traitor! to thy shame of thee

True tidings will I bear."—"Off," he replied,

"Tell what thou list; but as thou escape from hence

To speak of him whose tongue hath been so glib,

Forget not: here he wails the Frenchman's gold.

'Him of Duera,' thou canst say, 'I mark'd,

Where the starv'd sinners pine.' If thou be ask'd

What other shade was with them, at thy side

Is Beccaria, whose red gorge distain'd

The biting axe of Florence. Farther on,

If I misdeem not, Soldanieri bides,

With Ganellon, and Tribaldello, him

Who op'd Faenza when the people slept."

We now had left him, passing on our way,

When I beheld two spirits by the ice

Pent in one hollow, that the head of one

Was cowl unto the other; and as bread

Is raven'd up through hunger, th' uppermost

Did so apply his fangs to th' other's brain,

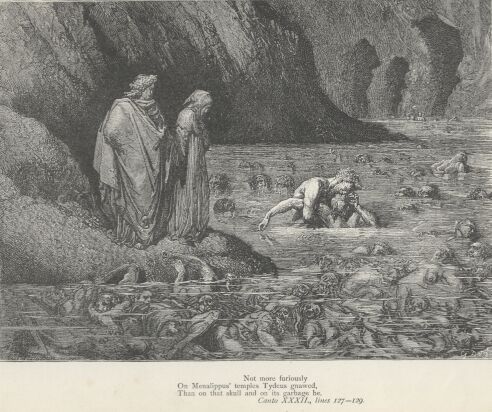

Where the spine joins it. Not more furiously

On Menalippus' temples Tydeus gnaw'd,

Than on that skull and on its garbage he.

"O thou who show'st so beastly sign of hate

'Gainst him thou prey'st on, let me hear," said I

"The cause, on such condition, that if right

Warrant thy grievance, knowing who ye are,

And what the colour of his sinning was,

I may repay thee in the world above,

If that, wherewith I speak be moist so long."

CANTO XXXIII

HIS jaws uplifting from their fell repast,

That sinner wip'd them on the hairs o' th' head,

Which he behind had mangled, then began:

"Thy will obeying, I call up afresh

Sorrow past cure, which but to think of wrings

My heart, or ere I tell on't. But if words,

That I may utter, shall prove seed to bear

Fruit of eternal infamy to him,

The traitor whom I gnaw at, thou at once

Shalt see me speak and weep. Who thou mayst be

I know not, nor how here below art come:

But Florentine thou seemest of a truth,

When I do hear thee. Know I was on earth

Count Ugolino, and th' Archbishop he

Ruggieri. Why I neighbour him so close,

Now list. That through effect of his ill thoughts

In him my trust reposing, I was ta'en

And after murder'd, need is not I tell.

What therefore thou canst not have heard, that is,

How cruel was the murder, shalt thou hear,

And know if he have wrong'd me. A small grate

Within that mew, which for my sake the name

Of famine bears, where others yet must pine,

Already through its opening sev'ral moons

Had shown me, when I slept the evil sleep,

That from the future tore the curtain off.

This one, methought, as master of the sport,

Rode forth to chase the gaunt wolf and his whelps

Unto the mountain, which forbids the sight

Of Lucca to the Pisan. With lean brachs

Inquisitive and keen, before him rang'd

Lanfranchi with Sismondi and Gualandi.

After short course the father and the sons

Seem'd tir'd and lagging, and methought I saw

The sharp tusks gore their sides. When I awoke

Before the dawn, amid their sleep I heard

My sons (for they were with me) weep and ask

For bread. Right cruel art thou, if no pang

Thou feel at thinking what my heart foretold;

And if not now, why use thy tears to flow?

Now had they waken'd; and the hour drew near

When they were wont to bring us food; the mind

Of each misgave him through his dream, and I

Heard, at its outlet underneath lock'd up

The' horrible tower: whence uttering not a word

I look'd upon the visage of my sons.

I wept not: so all stone I felt within.

They wept: and one, my little Anslem, cried:

'Thou lookest so! Father what ails thee?' Yet

I shed no tear, nor answer'd all that day

Nor the next night, until another sun

Came out upon the world. When a faint beam

Had to our doleful prison made its way,

And in four countenances I descry'd

The image of my own, on either hand

Through agony I bit, and they who thought

I did it through desire of feeding, rose

O' th' sudden, and cried, 'Father, we should grieve

Far less, if thou wouldst eat of us: thou gav'st

These weeds of miserable flesh we wear,

And do thou strip them off from us again.'

Then, not to make them sadder, I kept down

My spirit in stillness. That day and the next

We all were silent. Ah, obdurate earth!

Why open'dst not upon us? When we came

To the fourth day, then Geddo at my feet

Outstretch'd did fling him, crying, 'Hast no help

For me, my father!' There he died, and e'en

Plainly as thou seest me, saw I the three

Fall one by one 'twixt the fifth day and sixth:

Whence I betook me now grown blind to grope

Over them all, and for three days aloud

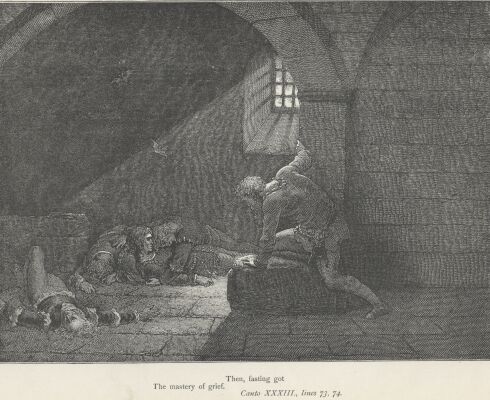

Call'd on them who were dead. Then fasting got

The mastery of grief." Thus having spoke,

Once more upon the wretched skull his teeth

He fasten'd, like a mastiff's 'gainst the bone

Firm and unyielding. Oh thou Pisa! shame

Of all the people, who their dwelling make

In that fair region, where th' Italian voice

Is heard, since that thy neighbours are so slack

To punish, from their deep foundations rise

Capraia and Gorgona, and dam up

The mouth of Arno, that each soul in thee

May perish in the waters! What if fame

Reported that thy castles were betray'd

By Ugolino, yet no right hadst thou

To stretch his children on the rack. For them,

Brigata, Ugaccione, and the pair

Of gentle ones, of whom my song hath told,

Their tender years, thou modern Thebes! did make

Uncapable of guilt. Onward we pass'd,

Where others skarf'd in rugged folds of ice

Not on their feet were turn'd, but each revers'd.

There very weeping suffers not to weep;

For at their eyes grief seeking passage finds

Impediment, and rolling inward turns

For increase of sharp anguish: the first tears

Hang cluster'd, and like crystal vizors show,

Under the socket brimming all the cup.

Now though the cold had from my face dislodg'd

Each feeling, as 't were callous, yet me seem'd

Some breath of wind I felt. "Whence cometh this,"

Said I, "my master? Is not here below

All vapour quench'd?"—"'Thou shalt be speedily,"

He answer'd, "where thine eye shall tell thee whence

The cause descrying of this airy shower."

Then cried out one in the chill crust who mourn'd:

"O souls so cruel! that the farthest post

Hath been assign'd you, from this face remove

The harden'd veil, that I may vent the grief

Impregnate at my heart, some little space

Ere it congeal again!" I thus replied:

"Say who thou wast, if thou wouldst have mine aid;

And if I extricate thee not, far down

As to the lowest ice may I descend!"

"The friar Alberigo," answered he,

"Am I, who from the evil garden pluck'd

Its fruitage, and am here repaid, the date

More luscious for my fig."—"Hah!" I exclaim'd,

"Art thou too dead!"—"How in the world aloft

It fareth with my body," answer'd he,

"I am right ignorant. Such privilege

Hath Ptolomea, that ofttimes the soul

Drops hither, ere by Atropos divorc'd.

And that thou mayst wipe out more willingly

The glazed tear-drops that o'erlay mine eyes,

Know that the soul, that moment she betrays,

As I did, yields her body to a fiend

Who after moves and governs it at will,

Till all its time be rounded; headlong she

Falls to this cistern. And perchance above

Doth yet appear the body of a ghost,

Who here behind me winters. Him thou know'st,

If thou but newly art arriv'd below.

The years are many that have pass'd away,

Since to this fastness Branca Doria came."

"Now," answer'd I, "methinks thou mockest me,

For Branca Doria never yet hath died,

But doth all natural functions of a man,

Eats, drinks, and sleeps, and putteth raiment on."

He thus: "Not yet unto that upper foss

By th' evil talons guarded, where the pitch

Tenacious boils, had Michael Zanche reach'd,

When this one left a demon in his stead

In his own body, and of one his kin,

Who with him treachery wrought. But now put forth

Thy hand, and ope mine eyes." I op'd them not.

Ill manners were best courtesy to him.

Ah Genoese! men perverse in every way,

With every foulness stain'd, why from the earth

Are ye not cancel'd? Such an one of yours

I with Romagna's darkest spirit found,

As for his doings even now in soul

Is in Cocytus plung'd, and yet doth seem

In body still alive upon the earth.

CANTO XXXIV

"THE banners of Hell's Monarch do come forth

Towards us; therefore look," so spake my guide,

"If thou discern him." As, when breathes a cloud

Heavy and dense, or when the shades of night

Fall on our hemisphere, seems view'd from far

A windmill, which the blast stirs briskly round,

Such was the fabric then methought I saw,

To shield me from the wind, forthwith I drew

Behind my guide: no covert else was there.

Now came I (and with fear I bid my strain

Record the marvel) where the souls were all

Whelm'd underneath, transparent, as through glass

Pellucid the frail stem. Some prone were laid,

Others stood upright, this upon the soles,

That on his head, a third with face to feet

Arch'd like a bow. When to the point we came,

Whereat my guide was pleas'd that I should see

The creature eminent in beauty once,

He from before me stepp'd and made me pause.

"Lo!" he exclaim'd, "lo Dis! and lo the place,

Where thou hast need to arm thy heart with strength."

How frozen and how faint I then became,

Ask me not, reader! for I write it not,

Since words would fail to tell thee of my state.

I was not dead nor living. Think thyself

If quick conception work in thee at all,

How I did feel. That emperor, who sways

The realm of sorrow, at mid breast from th' ice

Stood forth; and I in stature am more like

A giant, than the giants are in his arms.

Mark now how great that whole must be, which suits

With such a part. If he were beautiful

As he is hideous now, and yet did dare

To scowl upon his Maker, well from him

May all our mis'ry flow. Oh what a sight!

How passing strange it seem'd, when I did spy

Upon his head three faces: one in front

Of hue vermilion, th' other two with this

Midway each shoulder join'd and at the crest;

The right 'twixt wan and yellow seem'd: the left

To look on, such as come from whence old Nile

Stoops to the lowlands. Under each shot forth

Two mighty wings, enormous as became

A bird so vast. Sails never such I saw

Outstretch'd on the wide sea. No plumes had they,

But were in texture like a bat, and these

He flapp'd i' th' air, that from him issued still

Three winds, wherewith Cocytus to its depth

Was frozen. At six eyes he wept: the tears

Adown three chins distill'd with bloody foam.

At every mouth his teeth a sinner champ'd

Bruis'd as with pond'rous engine, so that three

Were in this guise tormented. But far more

Than from that gnawing, was the foremost pang'd

By the fierce rending, whence ofttimes the back

Was stript of all its skin. "That upper spirit,

Who hath worse punishment," so spake my guide,

"Is Judas, he that hath his head within

And plies the feet without. Of th' other two,

Whose heads are under, from the murky jaw

Who hangs, is Brutus: lo! how he doth writhe

And speaks not! Th' other Cassius, that appears

So large of limb. But night now re-ascends,

And it is time for parting. All is seen."

I clipp'd him round the neck, for so he bade;

And noting time and place, he, when the wings

Enough were op'd, caught fast the shaggy sides,

And down from pile to pile descending stepp'd

Between the thick fell and the jagged ice.

Soon as he reach'd the point, whereat the thigh

Upon the swelling of the haunches turns,

My leader there with pain and struggling hard

Turn'd round his head, where his feet stood before,

And grappled at the fell, as one who mounts,

That into hell methought we turn'd again.

"Expect that by such stairs as these," thus spake

The teacher, panting like a man forespent,

"We must depart from evil so extreme."

Then at a rocky opening issued forth,

And plac'd me on a brink to sit, next join'd

With wary step my side. I rais'd mine eyes,

Believing that I Lucifer should see

Where he was lately left, but saw him now

With legs held upward. Let the grosser sort,

Who see not what the point was I had pass'd,

Bethink them if sore toil oppress'd me then.

"Arise," my master cried, "upon thy feet.

The way is long, and much uncouth the road;

And now within one hour and half of noon

The sun returns." It was no palace-hall

Lofty and luminous wherein we stood,

But natural dungeon where ill footing was

And scant supply of light. "Ere from th' abyss

I sep'rate," thus when risen I began,

"My guide! vouchsafe few words to set me free

From error's thralldom. Where is now the ice?

How standeth he in posture thus revers'd?

And how from eve to morn in space so brief

Hath the sun made his transit?" He in few

Thus answering spake: "Thou deemest thou art still

On th' other side the centre, where I grasp'd

Th' abhorred worm, that boreth through the world.

Thou wast on th' other side, so long as I

Descended; when I turn'd, thou didst o'erpass

That point, to which from ev'ry part is dragg'd

All heavy substance. Thou art now arriv'd

Under the hemisphere opposed to that,

Which the great continent doth overspread,

And underneath whose canopy expir'd

The Man, that was born sinless, and so liv'd.

Thy feet are planted on the smallest sphere,

Whose other aspect is Judecca. Morn

Here rises, when there evening sets: and he,

Whose shaggy pile was scal'd, yet standeth fix'd,

As at the first. On this part he fell down

From heav'n; and th' earth, here prominent before,

Through fear of him did veil her with the sea,

And to our hemisphere retir'd. Perchance

To shun him was the vacant space left here

By what of firm land on this side appears,

That sprang aloof." There is a place beneath,

From Belzebub as distant, as extends

The vaulted tomb, discover'd not by sight,

But by the sound of brooklet, that descends

This way along the hollow of a rock,

Which, as it winds with no precipitous course,

The wave hath eaten. By that hidden way

My guide and I did enter, to return

To the fair world: and heedless of repose

We climbed, he first, I following his steps,

Till on our view the beautiful lights of heav'n

Dawn'd through a circular opening in the cave:

Thus issuing we again beheld the stars.

|