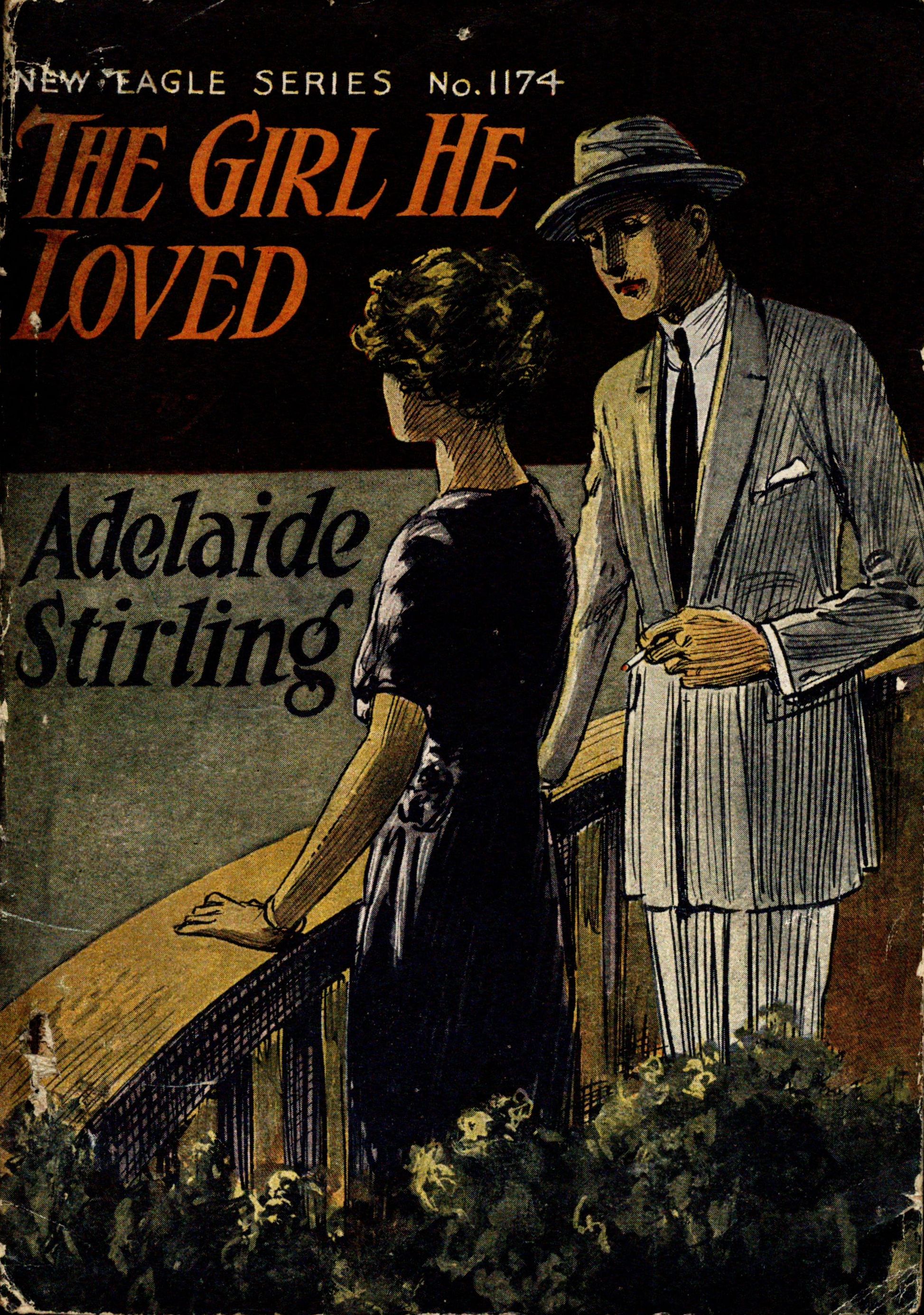

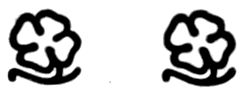

Title: The girl he loved

or, Where love abides

Author: Adelaide Stirling

Release date: October 30, 2025 [eBook #77154]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Street & Smith, 1900

Credits: Demian Katz and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (Images courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University.)

BY

ADELAIDE STIRLING

Author of “Saved from Herself,” “Her Evil Genius,” “A Forgotten Love,” “Love and Spite”—published in the New Eagle Series.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1900

By Street & Smith

The Girl He Loved

(Printed in the United States of America)

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian.

CHAPTER I. SWEETHEARTS.

CHAPTER II. THE PERSON IN BLACK.

CHAPTER III. A GIFT OF JUDAS.

CHAPTER IV. “A HORRID OLD MAN!”

CHAPTER V. HER WEDDING-DAY.

CHAPTER VI. A VERY CLEVER PERSON.

CHAPTER VII. HER LADYSHIP SHUFFLES THE CARDS.

CHAPTER VIII. “A BIT OF THE TRUTH.”

CHAPTER IX. REVENGE—AND A BALLROOM.

CHAPTER X. A TIRING DAY.

CHAPTER XI. NEWS OF ADRIAN.

CHAPTER XII. THE ICY BARRIER.

CHAPTER XIII. IN LEVALLION’S HOUSE.

CHAPTER XIV. A DOVE-COLORED GOWN.

CHAPTER XV. A WOMAN’S RING.

CHAPTER XVI. THE SIN OF SYLVIA ANNESLEY.

CHAPTER XVII. THE SEALED LETTER.

CHAPTER XVIII. A GROWING CLOUD OF WITNESSES.

CHAPTER XIX. IN OUTER DARKNESS.

CHAPTER XX. A WICKED WOMAN’S TONGUE.

CHAPTER XXI. WHITE POPPIES OF OBLIVION.

CHAPTER XXII. THE MOONLIGHT PICNIC.

CHAPTER XXIII. THE DARK GLASS.

CHAPTER XXIV. ALONE WITH THE DEAD.

CHAPTER XXV. A DEAD MAN’S SWEETHEART.

CHAPTER XXVI. TRIFLES LIGHT AS AIR.

CHAPTER XXVII. THE EVIDENCE IN THE CASE.

CHAPTER XXVIII. “I SAW—NO ONE!”

CHAPTER XXIX. “WILFUL MURDER.”

CHAPTER XXX. A CLOUD OF BLOOD.

CHAPTER XXXI. A BAD MOVE.

CHAPTER XXXII. A TRIVIAL INCIDENT.

CHAPTER XXXIII. LEVALLION’S HEIR.

CHAPTER XXXIV. “FALSE AS A PACK OF CARDS.”

CHAPTER XXXV. GOOD-BY.

CHAPTER XXXVI. A MOUSE-HOLE.

CHAPTER XXXVII. A GRAY-LINED CLOAK.

CHAPTER XXXVIII. ARRESTED.

CHAPTER XXXIX. MR. JACOBS.

CHAPTER XL. AT THE HINGES OF DEATH.

CHAPTER XLI. “I LOVED YOU BEST.”

SWEETHEARTS.

“Thomas, my son!”

The voice came darkly from the scullery window, and Sir Thomas Annesley gave a guilty start where he knelt in the kitchen garden.

“Oh! It’s you!” he cried, with relief. “I thought it might be her ladyship, and I didn’t want her.”

He hastily covered in a small grave he was making in the parsley-bed, and his sister poked her bronze head from the open window with some curiosity.

“What are you doing?” she inquired.

“Oh, nothing! Just putting away something. There is nothing like a hole in the ground. What on earth are you doing in the scullery?” eying the unwonted smartness of as much of Miss Ravenel Annesley’s toilet as was visible. “What have you got on your Sunday frock for? Have you been blacking the family boots in it?”

“If it’s anything to eat you’ve buried, the cats will dig it up again!” loftily ignoring his question, except for a guilty glance at her lilac muslin gown.

“No cat”—calmly—“will dig this up, for I’m going to do it myself first! Come out, why don’t you?”

“I’m coming.” Miss Annesley vaulted nimbly from the window with much display of her only pair of black silk stockings. “You don’t see her ladyship anywhere, do you, Tommy? Because I’ve an—an errand in the quarry, and I don’t want her to sniff it out.”

“She can’t sniff a quarter of a mile”—comfortably. “She’s gone down to sit by the lake without any hat; said she had neuralgia. But I know she’s gone to bleach her golden hair.”

“She does bleach her hair,” Ravenel remarked thoughtfully. “It was the most awful color yesterday—a sort of green! I heard her giving it to the Umbrella for making a mistake.”

Sir Thomas Annesley lit a contraband cigarette.

“And yet,” he said blandly, “it was not the Umbrella who changed the bottle! Her ladyship kicked Mr. Jacobs, and any one who kicks my dog has misfortunes. I’ll walk over to the quarry with you!” affably.

“No, Tommy dear!” with guilty haste. “I—I don’t require you.”

Sir Thomas coughed.

“Don’t blame me then if her ladyship sends the old Umbrella all over the country for you when you’re missed. I’ll have to kill that maid some day! Do you know, she listens at the door when we’re alone?”

“Much good she’ll get!” contemptuously, marching on under the blossoming apple-trees with the sun flecking the lovely bronze of her hair with red gold. “Look here, Tommy, you come as far as the hedge, and just give a cooee if you see the Umbrella or her ladyship.”

“Can’t. I’m going over to the barracks to see Gordon.”

“I wouldn’t! It would be”—she was not looking at him—“a waste of time.”

“Oh!” Sir Thomas winked vulgarly, as he observed a lovely carnation grow and deepen in his sister’s cheeks. “I see. Well, go on, my dear! I don’t blame you; only,” in hasty addition as they reached the hedge, “keep your eye peeled. The Umbrella is active, and also far-sighted. I don’t recommend the quarry myself; it is too like being a mouse in a bowl. Give me a wood for such undertakings! And mind you’re back by dinner, for if her ladyship sees you sneaking in with your Sunday blouse on she’ll put two and two together. Meantime, I’ve gone over to the barracks to see Gordon. You mind that when you come home!”

“You’re a duck, Thomas, some day I’ll reward you,” returned the vision in mauve muslin, disappearing with some pains through the whitethorn hedge.

But Sir Thomas only grunted. He approved of his sister’s adorer because Lady Annesley did not, but he privately considered that meeting a handsome, penniless hussar was wasting time.

“However, Mr. Jacobs,” he observed, as that disreputable bull-terrier joined him, “anything for business, and we’re growing old. And it is my belief that my lady wants to marry Ravenel to that old Lord Levallion, and I’ll see her blowed first.”

He sat down on the bank at the foot of the hedge and pulled his hat over his eyes. They were worldly wise eyes for a boy of sixteen; but to have Lady Annesley for a stepmother was a liberal education. Old Sir Thomas had married her in haste, and, fortunately for himself, had died too soon to have time to repent at leisure. He was poor; his new wife had been supposed to be rich; but her fortune turned out to be about as real as her complexion—there was just enough of it to swear by. Annesley Chase was mortgaged too deeply for the widow’s small income even to pay the interest; when young Sir Thomas came of age it would be foreclosed and sold over his head, unless money came from the skies. And yet Lady Annesley, even while she sat and saw the interest piling up against her, had no idea of letting Annesley Chase go. A snug old age in the dower-house appearing to her more inviting than spending her declining years in a semidetached villa, she was even now taking steps to secure it by the simple scheme of a rich marriage for Ravenel, and later and harder, for Sir Thomas. In the meantime, she provided the stepchildren, who were her only stock in trade, with bread and butter. Thin bread and thinner butter, perhaps; but still she fed them. And they hated her cordially—Ravenel from having seen her father’s last days made wretched; Tommy from a far-sighted distrust that grew on him every day.

But Ravenel just now had no thoughts for her stepmother, nor of how she was improving the long hours of the May afternoon. Over the short grass of the field above the quarry pits she was walking with the air of one having an infinity of time and no particular destination. Her heart might be galloping before her, but it was not good for captains of hussar regiments to know it. She sailed on demurely under the shade of an ivory-white parasol—it was one of Lady Annesley’s, and her stepdaughter hoped devoutly there would not be a hue and cry for it while it was out—as if she had not a care in the world. Yet a sharp color came to her clear cheeks as she neared the quarry pit.

Suppose he had not come!

The thought made her feel chilly in the warm May sunshine. For one breathless moment she was afraid to lift her eyes from the short grass lest she might look in vain for Adrian Gordon. And so nearly walked over him where he lay stretched on the warm, green sod at the edge of the quarry.

Miss Annesley dropped her pirated parasol.

“Oh!” she cried, as he sprang to his feet. “I nearly walked over you.”

“Tread lightly then, for my heart is under your feet,” quoted the man, with a little laugh of pure pleasure. He took both her hands and looked down into her gray-blue eyes.

“I began to think, Miss Annesley,” he remarked gravely, “that you were not coming. Another ten minutes and I should have walked up to your hall door and paid a polite visit,” his strong, fine hands holding hers with utter content.

The girl looked up at him where he stood bareheaded, the sun on his close-cropped, fair hair. How tanned and strong and good to look at he was! And how sweet his gray eyes and his mouth under his fair mustache.

He caught her hands a little closer.

“You see,” he said; “you were just saved having to receive me under her ladyship’s nose. I would have braved even her tea rather than have gone back without seeing you.” He stooped to pick up her parasol, and she drew her hands from his left one that held them both.

“It wouldn’t have been any good your coming in state,” she returned calmly. “You would only have had ‘not at home’ said to you. Her ladyship is engaged to-day in renovating her charms.”

“I should have met you at the door if I’d started when I first thought of it! Would you have sent me away?” seating himself beside her in the shade of a flower-filled thorn-tree on the sharp slope down to the quarry. “I believe you would!” rather dashed.

“I should not, for an excellent reason. I didn’t come by the front door, but out of the scullery window,” gaily. “Her ladyship supposes I’m darning table-cloths. I’ve left Tommy down by the hedge to warn me if my flight is discovered.”

The laughter left Captain Gordon’s handsome eyes. He laid his brown hand on Ravenel’s white one.

“Tell me, my Nel,” he said softly; “do you love me, ever so little?”

“No!” very low. “Ever so little!” Did she not love him with all her soul and body, as she loved no one else in God’s world?

“How much do you love me? That much?” measuring off a tiny space with her two hands, for he had them both now, and Lady Annesley’s lace parasol had rolled where it would down the quarry.

“Not at all?”

“Not at all,” but she barely whispered it.

“Do you mean that, Nel?” he was whispering, too. “Because I love you—oh, you know how I love you!” he let her hands go. “Tell me, quick, do you mean it?”

Miss Annesley made no answer, only raised her eyes to his for the briefest instant. But it was long enough for Adrian Gordon.

“Sweetheart,” he said, and kissed her. “Nel, look at me; won’t you kiss me?”

“I—I don’t know.” But she did look at him, and, somehow, without either of their wills, their lips met. And at that long, gentle touch of the man’s lips on hers Ravenel Annesley gave her heart and her soul to his keeping, forever.

“My sweet,” he said, letting her go, “do you know, I’ve no right to ask you to marry me? I’ve no money.”

“Neither have I,” gaily. “Would you like to be off your bargain?”

“Don’t say it!” quickly. “It hurts too much. But money I must and will have to marry you. I mean the girl of my heart to have all she wants in this world—gowns and horses and happiness. It would kill me to see you as I’ve seen the wives of lots of poor men. Can you wait for me, sweet, for two years, while I go out to India?”

“India! What for?” the color left her face.

“Well! I’ve a second cousin, who has some influence. He’s not a man I like much, but he surprised me the other day by telling me that a friend of his out in India would offer me an appointment on his staff—he’s a general—if it were certain I’d accept. I—I said I would. It’s more than three times the pay I’m getting now and a chance in a thousand to get on in the service. I’d have to leave my regiment, but I’d do that—for you.”

“Adrian—not now!” she whispered. “We’re so happy.” Her heart fairly turned over at the thought of Annesley Chase without Adrian Gordon quartered ten miles off, of the long, empty summer days.

“We’ll be as happy again,” he answered wistfully, “and the sooner I go the sooner I’ll be back. But I wouldn’t go at all if I saw any other way. I’m afraid to leave you with your stepmother.”

“She can’t marry me out offhand to a slug or a snail, and those are the only visitors we ever have. My charms”—dryly—“have doubtless not yet been noised abroad.”

“I believe you wish they had been!” quite as dryly. “You’re a bundle of vanity, Miss Annesley, and I believe you’ve got a temper—and you’re proud——” he paused eloquently.

“Go on,” returned his charmer calmly. “Don’t mind me! And when you’re done I’ll tell you what I am—quite good enough for you!”

Her eyes met his with sweet insolence, fearless for all their softness, and the man’s face changed.

“You’re too good, that’s one thing,” he said slowly. “And for another, you’re too proud. I know you! If anything went wrong between us, and it was my fault, you’d never give me a chance to explain.”

Ravenel looked at him, as he sat beside her, with the May sun full on his face, that was meant to be fair, but was turned a clear pale-bronze by wind and weather; full on his tawny, gold mustache, and the clear-cut lines of his cheek and chin. Strong and cold and proud that face was, till you looked at the man’s eyes or saw him smile. But now he was not smiling, and a quick pang caught at the girl’s heart. Adrian Gordon to talk of pride!

She flung out both her hands to him, as she had never done before.

“Listen!” she cried passionately. “It’s you who are proud; not I! Offend me, and I will give you all the chances on earth to explain; but you—oh, I don’t believe you would ever forgive anything.”

Her eyes, that had been so gay, so full of sweet mockery, were brimming with tears, and Gordon caught her to him jealously.

“There will never anything come between us,” he said as he kissed her, “not between the girl I love and me!”

THE PERSON IN BLACK.

Behind a rock, not two yards from Captain Gordon’s flat young back, something stirred—stirring so faintly that even a thrush in its nest in the hawthorn bush did not hear it. Perhaps the sour-faced person in black who knelt on the grass, ostensibly digging dandelions for a complexion salad, had been there for a long time; or, perhaps, it had not been hard to evade the sentry on the hedge and bring up in good ear-shot of the two people who were blind and deaf to everything but themselves.

“Heaps of things can come between us,” Ravenel was retorting dolefully. “Lady Annesley can. And Tommy says the Umbrella—that beast of a maid of hers—tells her everything we do.”

The person in black bridled angrily behind her rock. She had come from curiosity; she would stay now for spite. The Umbrella, indeed!

Gordon laughed.

“Why do you call her that?”

“Oh, because she’s a framework of bones with limp black silk over them—just like an umbrella shut up! But she’s a vicious wretch, too, and I hate her.”

The unseen listener’s eyes narrowed in her flat face.

“Well, never mind her; she can’t worry us!” hastily. “This is the only thing that matters just now. My cousin wired to General Carmichael that I’d accept his offer, and—got an answer. Nel, I must go in a week!”

“Well?” she did not look at him.

“Well, I’m going!” his handsome face drawn and hard. “But I won’t leave you like this. I want you to marry me before I go.”

“But you couldn’t take me with you?” a wild hope made her voice shake.

“No! But I could send for you, or come when I could get leave and carry you off. Look here, my heart,” with gentle strength, “if I must go I want to leave my wife behind me. Then I shall know nothing can ever come between us.”

“Oh,” her cheek reddened, “I can’t marry you! How could I?” though the very thought of being Adrian’s wife made life heaven.

“There’s Tommy.”

Gordon smiled.

“Is that all? Only Tommy! When I come back for you we’ll take Tommy, too; will that do? Or, do you think you’ll find me an insufferable husband? Tell me. Why don’t you look at me, sweetheart?”

“Because I don’t want to,” returned Miss Annesley, with scarlet cheeks and a truthful tongue.

“Say you’ll marry me!” he demanded. “Say yes—unless you don’t love me.”

Very deliberately she looked at him, saw the love and truth in his eyes, the strength and beauty of his face, that was pale with earnestness.

“Yes,” she whispered, so that he could hardly hear; but he knew without hearing—and the silent woman behind the rock knew, too, and strained her ears.

“Then will you do this?” said Gordon. “The curate at Effingham went to school with me. He’ll marry us if I get a special license. All you’ll have to do is to walk over to Effingham—which is really your parish church, though you don’t go there—with me, and be married. No one will know, unless you like to tell Tommy. And I’ll bring you straight home from the church door. But you’ll belong to me, and I can defy her ladyship or any one else to make trouble between us. Will you do that?”

She nodded, her face like a crimson flower.

“Yes, Adrian,” he prompted; but she spoke with a sudden flash of her spirit.

“Your wife or no one else’s in the world!” she cried, “unless—you change your mind and throw me over.”

Gordon caught her up like a child.

“Oh, you silly, silly!” he cried. “I’ll not give you a chance to be any one else’s wife; don’t flatter yourself. But I’ve no right to so sweet a thing as you. What you ought to do is refuse me and marry my cousin.”

“I don’t even know his name.”

“That’s a trifle. He has money enough to buy this county and not know it.”

“He hasn’t money enough to buy me!” with a quick flash of her eyes. “Oh!” with sudden remembrance of the world about her, “I must go! Look how long the shadows are.”

“Wait—just one second! I’ve something for you,” he was feeling in his pocket. “I meant it to be diamonds, but they say these things—though, of course, it’s nonsense—lose their light if things go wrong with—any one you care for!”

He drew out a velvet case, and there shone into Ravenel Annesley’s eyes the green fire of a half-hoop of emeralds, curiously set in a kind of mosaic of small diamonds and opals. The thing was wonderful in a queer, barbaric way as it blazed in the sun. The girl who looked at it stood speechless.

“Don’t you like it?” his face falling, for he had searched London for a ring unlike any others.

“I—I love it! But——” she stopped with dismay.

Opals—every one knew what luck opals brought. And emeralds all the world over meant “forsaken.”

“Opals aren’t lucky,” she said hastily, and left the green stones out of the question; “but this is too beautiful to bring bad luck. And I suppose it’s all nonsense really! Adrian, do you know, I never had a ring in my life?” shaking from her the senseless dread she felt of this one.

“You’re going to have two now. This to-day and another next week,” he was slipping the fiery-green wonder on her third finger. “‘Till death do us part,’” he quoted softly. “That belongs to the next ring, but I can say it with this one.”

“Death, or Lady Annesley!” sharply, her eyes full of quick tears. “She hates me, Adrian, and she doesn’t like you.”

“It can’t hurt either of us, Nel!” with the little backward jerk of his head the girl loved.

“Why do you never call me Ravenel?” she said irrelevantly, for there was no sense in wasting good time talking about her ladyship.

“Not like you!” promptly. “Means some one quite different. Mind you, never let any one call you Nel till I come back again,” with a sudden curious jealousy.

“No one will want to,” dolefully. “Oh! Adrian; do you really mean to go next week?”

“I must,” his face grew dark, hard-bitten; for it was like dying to leave her. “And the worst of it is I’ll be so busy. I’ll have to go to London to get my kit, and say a decent word to my cousin, and sit through a farewell dinner at mess—that’ll be about as lively as a funeral!—the night before I leave, when I shall be mad to be with you. But we’ll have one day together if everything goes undone. And you’ll go with me to Effingham, Miss Annesley, and come back Nel Gordon!”

But she sat pale and quiet.

“It seems so mad, so impossible!” she said at last, as if it were wrung from her. “And I believe my stepmother would kill me if she found out.”

“That’s about the only thing she couldn’t do,” shortly. “Do you think I won’t take care of her claws for you? Look here, besides, the day we go to Effingham there’ll be the duchess’ garden-party. I’ll manage to get there. If I can’t, I’ll send you a note to say what day I am coming to take you to Effingham. After that, sweet, we can laugh at her ladyship.”

“You’ll be gone! We won’t be able to laugh at anything!” forlornly.

“You’ll be my wife,” something flashed into his eyes that boded no good to any one that dared lift a finger against Adrian Gordon’s dearest. “I’ll be able to write to you and you to me. Some day I’ll come and carry you off, no matter what Lady Annesley may be pleased to say. The only thing is,” a sudden pity in the masterful protecting hand on hers, “it’s a pretty poor match for you, my Nel. And a doleful wedding in an empty church to a man who can’t even keep you is a selfish bit of work—it makes me feel a beast! You ought, you know, to marry a lord—with a choral service, and two bishops, and a church full of fine people to make it all proper,” his voice was jesting, but his eyes were sad enough, and he held her hand as if he never could let it go.

“Don’t talk like that!” she cried sharply. “It makes me feel as if some one were walking over my grave. What have I got to do with lords and bishops at my wedding? I’d be miserable. I’d——” she could not go on. What made her see, as if in a vision, a strange church, filled with sweet people, whispering indifferently while the organ pealed, and the bride, all in white—with a heart of stone—came up the aisle on feet that would hardly carry her, since it was not Adrian Gordon who waited at the altar? There was a look on her face as she stared in front of her, wide-eyed, that made Gordon catch her to him. A prescient look, as of one who sees for a shuddering moment the curtain lifted from the future.

“What’s the matter? You’re not afraid?” he whispered. “I’ll take care of you, my sweet; you know that! May God treat me as I treat you, my wife.”

Lip to lip, soul to soul, they kissed each other. She was shaking when he let her go; afterward it was small comfort to him to remember it, nor the real terror in her voice when she spoke.

“Oh! I’ve stayed too late. And the ring, I daren’t wear it. You mustn’t come with me. She mustn’t know you were here.” She dragged up her neck-ribbon and put the ring on it, slipping it round her neck, inside her collar, pushing it out of sight with miserable care. And the watcher behind the rock—who was stiff and much fatigued—saw her do it.

“Rings!” she reflected, coming cautiously out as the pair vanished, and rubbing one foot that had gone to sleep, “and weddings at Effingham—we’ll see!” pins and needles adding vigor to her thoughts. “Old Umbrella, indeed!” and her ladyship’s confidential maid moved stiffly off in a devious direction that took her to Annesley Chase quite unobserved.

A GIFT OF JUDAS.

“Oh!” said Ravenel Annesley to the empty schoolroom, the ill-spread breakfast-table. She stared at the small envelope that lay on her plate with a breathless, helpless joy. Since this four days past she had hoped for it in vain.

“I never thought he’d write by post!” she thought, pouncing on it and inspecting every inch of it, from the London postmark to the last letter of the address. “But her ladyship couldn’t have suspected it was from Adrian, or I never would have seen it! It was just that London postmark that saved me!”

She turned it over sharply with the horrid thought that perhaps she had only got it after Lady Annesley knew what was in it, for the post-bag always went to her bedroom, and her ladyship’s prejudices were few. But the clean, red seal on the back of it reassured her no one had tampered with that clear-cut A. Tommy, sauntering in, whistled as he looked from his sister’s face to the envelope she was tearing open.

“My Nel,” she read breathlessly.

“I find I can go to the duchess’ to-morrow. I was afraid I couldn’t manage it. My ship sails on the 15th, so the 14th is our only day. I have arranged everything, got the license, seen the curate at Effingham, and I’ll come to the back gate for you at three on the 14th, which is our only chance for Effingham, as my ship sails a day sooner than I thought. Will it be very hard for you to get away? But you’ll do it, won’t you? Bring Tommy if you like. It does not seem true that the next time I see you will be on our wedding-day, does it, sweetheart? I feel as though I were hurrying you brutally, but it is our only chance. Excuse pencil and haste, but I’m writing in another man’s rooms, and his ink won’t work.

“Always yours—my very dearest,

“Adrian.”

But Miss Annesley bestowed no attention on the pencil-scrawl or the dates written in figures, which Lady Annesley would have considered tempting Providence.

“To-day is the twelfth,” she thought joyfully. “I’ll see him to-morrow at the duchess’. Oh, if I only had something fit to wear!”

“Look here,” said Sir Thomas suddenly. “When you have done moaning over that precious letter I wish to discourse. Are you going to marry Gordon?”

“Shut up, Tommy!” she was scarlet. “Some one might hear.”

“Who could?” scornfully. “The Umbrella’s at her breakfast. Are you? Because, I should if I were you! it may be your only chance,” significantly.

“Yes, I am!” she said defiantly, and afterward was glad she had told no more.

“But what do you mean?” for his face was sober.

“Only that somehow I think her ladyship’s in mischief. She’s been eying you like a cat lately. I feel afraid she may be on to you and Gordon.”

“I don’t care if she is.” Somehow she could not tell all her wild plan to Tommy. “I’m engaged to him. Why should I care?”

“You don’t now, but you will when her eye’s on you,” shrewdly.

“I’ll soon find out. She wants me after breakfast,” bestowing Adrian’s note in a safe pocket. “I suppose it’s about the duchess’ party to-morrow. Do you know I’m to go?”

The boy nodded.

“Good old duchess!” he said disrespectfully. “Ever see her on a bicycle? She’s gorgeous. You’ll never be a fine woman like that unless you make her ladyship give us more to eat,” dolefully.

“What do you bet—she’s having sweetbreads up-stairs?”

“Don’t bet,” concisely. “Met them going up. I’ll go up myself now, Tommy, and hear the worst.”

She marched out of the untidy old schoolroom, where she and Tommy had their meals, and through the bare passages to the only luxurious room in the house. It was like going into another world, a world of scent and rose-colored hangings and mirrors, silver-topped bottles and cushions. On a sofa sat its owner and in the tempered light she was beautiful still. Yet she looked enviously at Ravenel standing in the doorway. With half her looks Sylvia Annesley would have married a duke.

“You wanted me?” Somehow Ravenel was nervous.

“Yes,” pointing to a chair; “about to-morrow. Have you anything to wear?”

“My Sunday frock,” coloring as she remembered when she had last worn it.

Lady Annesley let a gleam of amusement come into her eyes, since her back was to the light.

“That lavender thing! It can’t be fit.”

“It’s all right,” hastily. “It doesn’t matter what I wear.”

“Except that I fancy the duchess would like to see you decent.” So carelessly that no one would have dreamed that all her schemes might be made or marred by her step-daughter’s toilet at a country garden-party.

“It’s my lavender or nothing!” returned that young person not too amiably.

Lady Annesley’s answer made her jump.

“Not at all! I am going to give you a gown. I sent for you to try it on.”

“You!” It sounded more candid than polite. “Why? What for?” For her life she could not get out any thanks. Lady Annesley, who let her go cold in winter, to suddenly present her with a new dress. “I—I’d rather not,” she ended stiffly.

“Oh, you might see it first,” rather dryly. “Adams, Miss Ravenel’s gown!”

Ravenel watched the Umbrella go to a wardrobe.

“If she made it,” she thought, “I’ll never put it on!”

Sylvia Annesley read the obstinate face like print.

“You see,” she said lightly, “the whole county will be there to-morrow, and all the soldiers! You simply can’t go in a tumbled old muslin.”

All the soldiers! And Adrian had never seen her in a frock that was even new. Lady Annesley saw her waver.

“That is the little gown,” she said quickly. “Slip it on and decide afterward,” thinking that mention of the soldiers had done the business, and blessing the discretion of her maid without which she might have given her stepdaughter ten gowns and not known how to make her wear them.

For Ravenel had risen and was staring at the ivory-white, silk-lined muslin the Umbrella held.

There was not a spot of color about it, and as she gazed the girl knew that Adrian had never even dreamed of her as she would look in that filmy white frock.

“I can’t take it,” she faltered, but she let the Umbrella put it on her.

“The hat, Adams!” cried Lady Annesley quickly. “In the next room. Give me the scissors first. The collar is too high in the back.”

She snipped hastily once or twice, but Ravenel hardly felt the cold scissors as she stared down at her long skirt.

“There, look at yourself.” With a curious lingering touch, Lady Annesley pushed her to the glass. But the girl gave a little cry of astonishment.

Was this her very own self who stood so thin and tall, her bronze hair gleaming, her cheeks rose-red, her eyes—she turned from the mirror with sudden passion. No matter who gave her the gown she would wear it! would go all in white for Adrian Gordon’s eyes.

“Do you know it is very good of you?” She faced the woman in the yellow silk morning gown honestly. “I don’t deserve it.”

“It is not new. I had the things,” slowly. “Just turn and let me see how the train hangs.” She stooped gracefully, pulled the bodice down under the skirt, settled the train. She also had not been prepared for the dream of peach and carnation the girl looked in the white gown; had doubted if her one card were strong enough to play against the world-worn shrewdness of a man grown old in society. But she was confident enough now.

“I can snap my fingers at Captain Gordon, I fancy,” and she tightened her small hand. “He can’t blame any one but himself,” but she kept the scorn off her face till Ravenel had put on her every-day clothes and departed.

“Tommy,” the girl cried, bursting into the schoolroom and recounting her extraordinary tale, “fancy her giving me a dress! Do you think it means she’s beginning to like me?” wistfully.

“I don’t think—I know,” said Sir Thomas bluntly. “It means Lord Levallion. You bet your boots he’s going to that party.”

“What do you mean?” blankly. “I never heard of the man.”

“Her ladyship dropped that out the window,” producing a torn envelope. “It blew slap in my face. Dark-blue coronet, ‘Levallion’ on the back and ‘Lady An——’ torn through in front. And, sent by hand!”

“I don’t see what that’s got to do with the garden-party!”

“Don’t you?” getting up. “You’re a girl and can’t see past your nose. I tell you Levallion’s staying with the duchess. Aren’t you hungry? I’m going out to get that ginger beer I buried. I hooked some buns, too. We hadn’t too much breakfast.”

“We’ll get less after to-morrow,” following him briskly into the garden. “For I’m not going to speak to any nasty old Lord Levallion—not for ten gowns. I’m going to——” She stopped short, white with terror.

“My ring!” she cried wildly. “I took off my dress before her. She must have seen it.”

Both hands at her throat, she fumbled for her treasure; and leaned back against a convenient tree with her knees giving under her.

Ring and ribbon were gone!

“A HORRID OLD MAN!”

Lord Levallion was bored.

He hated garden-parties, and he had patiently endured the Duchess of Avonmore’s country omnium-gatherum from four o’clock until six. He could not go home, because he was staying in the house, and, retreat being impossible, he had revenged himself for his martyrdom on his old friend, Lady Annesley, by departing hastily on her eager offer to introduce him to her stepdaughter.

“I don’t see her just now,” Sylvia Annesley had said, with the smile he had once known so well, “but if you will come with me we shall easily find her!”

“No, thank you, Sylvia; I don’t care for little girls.”

Lord Levallion had the rudest drawl in the world when it pleased him, and he enjoyed Lady Annesley’s rage at it now. It was all very well to write her a note by way of amusing himself on a wet day, but it was another story to have her introduce him to a bread-and-butter miss.

“The woman wears well, though,” he reflected, as he adroitly drifted away from her. “Who would imagine it was fifteen years since I loved and rode away! I think a cigarette might assist me to endure to the end, if I can get away from this madding crowd. I’ll get back to town to-morrow, that’s one thing certain. The country is less in my line than ever.”

He pursued his leisurely way through the magnificent old gardens, round the end of the lake, and finally found a seat on a retired bench in the heart of a grove of trees. There was not a soul to be seen, and if it had not been for the mellow sound of a distant band Lord Levallion would not even have been reminded that he was at a party. He had smoked one cigarette, and was lighting another with a contented sigh, when he heard a quick step and a rustle of silk which caused him to look up sharply. Pray the gods Sylvia had not tracked him!

But it was not Sylvia. It was a strange girl, all in white from her hat to her shoes, and she did not even see him as she walked toward him along the quiet path where the light came dim and green through overarching boughs. She was magnificently handsome—and she was blind with tears that streamed down her face. Her white gown trailed unheeded on the gravel as she fumbled in her pocket for a handkerchief.

“Something must be very wrong,” Levallion reflected swiftly, “to make her ruin her skirt round the hem!”

But even in her tears she was gloriously beautiful, and he was not going to let her pass him.

Lord Levallion got up, dropped his cigarette, and took off his hat.

“I beg your pardon,” he said gravely. “I will go.” But he did not move.

Ravenel Annesley started furiously.

“I didn’t see you,” she said, with a sob in her throat. “I thought there was no one here. And—I wanted to be alone.”

She wiped the tears from her eyes savagely, with a morsel of a handkerchief; but they came again, and Levallion saw her chest lift with an uncontrollable sob.

“Do you want to stop crying?” he said quietly.

Ravenel stamped her foot.

“Of course I do, but I can’t!” she cried childishly.

“Then don’t be alone,” he returned. “If you stay by yourself you will cry till you are not fit to be seen. Sit down here by me instead, and talk. Oh, I know you’re wishing me miles away; but just try it! When you get to my age you will find it is always better to stop crying.”

His voice was cool and hard. It came on her nerves like iced water. She did not answer him, but she sat down on a corner of the bench limply, as if her feet could carry her no longer.

“Do you mind my cigarette? No,” as she shook her small, averted head. “Then I will smoke. Don’t rub your eyes unless you want the whole world to know you’ve been crying,” looking down his nose at the cigarette he was lighting. “And the more you have been crying the less you probably want people to know it.”

“No one would have known it if you hadn’t been here!” she said angrily. “Now I suppose you’ll tell the duchess.”

“Why the duchess?” Anything to make her talk. It was a sin to let so lovely a face be cried into hideousness. He hoped devoutly she would not blow her nose! Women usually did when they cried.

“It’s her party, so you must know her. And I don’t know whether you know any one else or not.”

“I have not the honor of knowing you, at all events,” he returned coolly. “So that I couldn’t tell the duchess if I wanted to—which I don’t.”

“It doesn’t matter who I am.” She bit her handkerchief desperately. “I wish I was anybody—I wish I were dead!”

“That is a wish you are certain to get—in time! It’s not worth while to cry because you despair of it,” blandly.

“I’m not crying.” She turned her small, white face to him, and her eyes were dry, if her lip still quivered.

“No, but you are extremely unhappy,” looking at her as indifferently as if he were not taking in every point in her lovely, mutinous face.

“So would you be. At least, I don’t know,” with frank rudeness. “Perhaps at your age you would not care.”

She bestowed a look on him for the first time, but without a shade of coquetry. The man might have been a tree or a stone for all she card. It was not the way women usually regarded Lord Levallion, and it interested him. He turned his high-bred, worn face, with the lines of forty-seven years on it, toward her with a keen glance which somehow reminded her of Adrian. The thought brought a fresh lump in her throat.

“I wish I could go home,” she said miserably. “I—I’ve lost something, and I’d like to get home and look for it. If it wouldn’t make a hue and cry I’d walk home now.”

She had not had one happy minute since discovering her ring was gone. Had turned from the wondering Tommy, digging for his beer in the parsley, and run up-stairs like a frantic, raging child, to the door of Lady Annesley’s room. And there something stopped her like a tangible thing. She stood motionless, with clenched hands, felt cold in the warm May air that flooded through an open window. Why had she come running up here like a fool, when she knew she dared not open that shut door in front of her and demand her ring of the woman inside?

“If I said Adrian had given me a ring she’d never let me set eyes on him again!” she thought, with more truth than she knew. “She knows I never had a ring. She’d ask—and what could I say? I might lie, but it’s no use to lie to a liar; they know too much. And, perhaps, she hasn’t taken it—perhaps I dropped it! I was out in the garden before breakfast. I’ll wait! I’ll tell Adrian to-morrow. It’s no use to give myself away for nothing.”

And here was to-morrow—and no Adrian. Man after man of his regiment she had seen, but she knew none of them. She could not go up to strange men and clamor for news of Adrian Gordon. Her heart felt like a stone when it grew too late to expect the man for whom she had come in that white gown that felt as if it burned her. She had slipped away from the crowd, away from Sylvia, like a child who cannot keep a brave front any longer. Where was Adrian? And how was she to bear the rest of this dreadful party?

“How far is ‘home’?” Levallion said suddenly.

“I don’t know. Five miles and more. I can’t walk in these,” with a sudden glance at her white suède shoes. “I’d ruin them—and they’re not mine. They and everything else were put on me in hopes that a horrid old man might admire me. Thank goodness, I haven’t even seen him! And I wouldn’t have spoken to him if I had!”

A sudden light arose on Lord Levallion’s horizon. This must be Sylvia’s stepdaughter.

“Ah!” he commented grimly. “What old man? Levallion?”

Ravenel nodded.

“She did not say so, of course, but I feel sure of it. Why? Do you know him?”

“As well as most people.” But he said it without much spirit. It did not somehow amuse him to be considered “a horrid old man.” He got up, rather stiffly.

“If you want to go home,” he said, “I will drive you. I am no more interested in this party than you. I will get a pony-cart at the stables and meet you at the turn of the avenue. It will fill up my time till dinner.”

“There isn’t going to be any dinner,” crossly. “There’s going to be supper, and the duchess has asked me to stay and dance afterward. If I have to stay here till eleven o’clock I sha’n’t be able to stand it.”

“Then don’t stay. You don’t”—the “horrid old man” rankled—“look fit to be seen in any case! If your chaperon is going to stay to supper, I will find her when I come back and tell her I took you home.”

“Will you?” Her face grew almost happy. She cared nothing at all for appearances, or that she had not been introduced to this stranger, who stood looking at her with cynical kindness.

“Yes! Come along,” he returned abruptly. “You needn’t thank me. I’m very much bored, and I’m going for my own amusement.”

“But how can you tell my stepmother, Lady Annesley? Do you know her?”

“You can write it,” producing a neat gold pencil and note-book and tearing out a leaf.

He watched her while she wrote. Truly Sylvia had done well to dress her all in white! Most women tried to please you without consulting your tastes, but Sylvia had not forgotten that he thought white the only wear for a pretty woman.

“There!” The girl handed him a scribbled note nervously. “You will be sure to give it to Lady Annesley?”

“I promise you,” with grave politeness. “Now, if you will be at the turn of the avenue in ten minutes I will have the cart there.”

Ravenel nodded. If it were twenty miles she would go home. She could not bear another half-hour at this miserable party.

There was not a soul to be seen as she sprang lightly up into the high, two-wheeled cart, never even asking how her strange friend was able to order out the duchess’ own pony. She leaned back wearily as they started, and the man beside her was too wise to try to make her talk.

In silence they drove through the quiet country lanes, the setting sun reddening the bronze of the girl’s hair and lending a false color to her listless face. When they reached the open door of Annesley Chase, she was down like a flash before he could get out.

“Thank you—oh, a hundred times!” she cried gratefully. “You will give Lady Annesley her note at once, won’t you?”

“At once,” lifting his hat. But the girl had run into the house.

Now was her time, while Lady Annesley was out. She tore off the smart white gown she had put on so carefully, and threw it on the floor. Then she got out Adrian Gordon’s letter and looked at it feverishly. There it was in black and white: “I can go to the duchess’. I was afraid I couldn’t manage it.”

Well, something must have happened! But at least she was at home again; she could look for her ring. And suppose he had not been able to go to-day, what did it matter? To-morrow would be her wedding-day, and after that nothing could come between them any more.

Pale, trembling, her heart heavy as lead, in spite of herself, she stole like a thief to her stepmother’s room. The Umbrella was down-stairs, and Ravenel hunted quickly in every drawer and box. It never struck her as being odd that they should be all unlocked, exactly as if the more thoroughly they were searched the better for their owner’s plans. And the girl, after thirty minutes, knew she looked in vain. Her ring was not in the room. Somehow and somewhere she must have lost it. She remembered that, like a fool, she had tied the ribbon in a bow. It was utterly inexplicable except for that.

As Ravenel crept away, utterly hopeless, Sylvia Annesley was standing in the duchess’ drawing-room, with a heart that beat high in joyful surprise.

“What!” she cried incredulously, “you drove her home? But you did not know her!”

“I met her,” Lord Levallion returned dryly, “during the afternoon. You had decked her out to meet the eye, hadn’t you?”

But Lady Annesley did not flinch. Instead, she did not seem to have heard his fleering voice. She had grown pale under her rouge, and she laid a quick, insistent hand on his arm.

“When did you go? What time?” she cried sharply. “And did you meet any one on the road? Was there any one waiting at the Chase when you got there?”

“No. There was not, to my knowledge—any one!” with an exact imitation of her tone. “No one either met or waylaid us.”

So that was the reason of the tears! Madam Sylvia had somehow tricked the girl into coming here, and now was frightened into her little shoes for fear she had not stayed long enough. For Lady Annesley’s smile, for once, was absent.

“Tell them to get my carriage, will you?” she said slowly. “I must go, too. That foolish, headstrong girl of mine may be ill. Perhaps you will come over to-morrow?”

To-morrow Lord Levallion had meant should see him in London. He shook his head for sole answer, but decided to wait a day all the same.

“Your stepdaughter seemed in excellent health when I left her,” he observed, turning away to send for her ladyship’s carriage. “But, all the same, I dare say you are wise to get home!”

She looked quite old, he saw, in her sudden anxiety, and he wondered cynically just what ailed her, for she scarcely said good-by as he saw her into her shabby fly.

That vehicle seemed to crawl to its impatient occupant. But at last she reached her own door, with as quick a step as Ravenel’s own, her room, where the Umbrella sat limply waiting.

“Adams, what time did Miss Annesley get home?” she demanded sharply. “Was there any one here? Quick! Any one?”

The Umbrella rose stolidly.

“Not when Miss Annesley came,” she said slowly, and her hearer thought she did it on purpose. “Everything has been all quite right, my lady. A gentleman called, though, and left his card.”

“It doesn’t matter,” sharply, but she glanced at it with such relief that her head swam, before she tore it to pieces. “It was no one I minded missing.”

“No, my lady.” And if there was the familiarity of a confidante in the woman’s tone Lady Annesley did not notice it, nor that she neatly collected the bits of torn card off the floor.

Her ladyship felt really dizzy with fatigue, or emotion, as she flung herself into a chair.

“I’ll dine up here,” she said slowly. It was all right and her net seemed to have caught Levallion, but such days were ageing. She had fought her Waterloo, and she felt the reaction even of victory. Tired to death, the weight of the rings on her slender hands felt unbearable. Her ladyship rose softly and hastily and locked the gorgeous things away.

HER WEDDING-DAY.

Half-past two o’clock, and her wedding-day!

Ravenel Annesley looked at herself in the glass curiously as at another person. She had on a clean white duck dress—having looked with a shudder at yesterday’s unlucky silk and muslin—nothing of her stepmother’s should go to her adorning on her wedding-day! But in her plain white gown she was lovely, and with a keen thrill of joy she knew it. Thank God, Adrian’s bride was pretty, even if she went to him in a cotton gown!

And in half an hour she would see him; tell him of her lost ring—for, think as she might, she could not see how either Lady Annesley or her maid could have taken or even seen it; her cotton slip bodice had been carefully buttoned over it—of yesterday’s party, and of how she had waited vainly for him. She opened her door and stole through the house. She would not take Tommy. She would go alone to church with Adrian; all alone, would promise and vow to be his always. She hurried through the garden and down to the back gate.

It was early still, and silly to expect him; yet she had a foolish pang of disappointment as she looked up and down the empty white road outside.

“He’ll be here in a minute,” she said to herself confidently, “and then I’ll feel happy again. I hope he won’t be angry about that ring. And I wish I knew how I lost it!”

She sat down in the shade just inside the gate and lost herself in a happy dream. Some day—soon perhaps—Adrian would come back from India, and carry her and Tommy off under her ladyship’s nose, who could go anywhere she pleased, for the Chase was certain to be sold over her head.

“And I shouldn’t care. I’ve been too wretched here,” she thought passionately. And then something startled her.

The stable clock had rung. Why was Adrian late, who was always so early?

“I never knew how awful it was to wait!” she cried, springing up. “I feel as if I couldn’t sit still. I’ll walk up and down till I count a thousand steps, and then I’ll look at the road again.”

But she paced a thousand steps, and a thousand again; there was no sign of Adrian Gordon.

“Oh!” in spite of herself she trembled, “it can’t be going to be like yesterday. He must be coming.”

Her heart quaking, she wished she had brought Tommy. This was too awful. The tears came to her eyes. She could not walk any longer, yet how could she sit still? She shivered in the hot, sweet sun.

“Oh, Adrian, hurry!” she whispered childishly, as if he must hear her; and then sat down on the green bank by the road as if she were suddenly weak. For the stable clock had struck four.

It was a long lane, and no one passed by to see a girl in a white frock sitting on the grass, careless of greening the spotless whiteness of her wedding-gown; no one looked with a wondering eye at the sick despair in her face, as she sat dumb and motionless—waiting for the man who by this time should have been her husband.

When the slow clock rang six, Ravenel Annesley got up, steadying herself carefully. She was chilly and stiff, and though she did not know it, broken-hearted.

Truth and honor and love, dead letters to her, she looked once more down the quiet lane to the quarry, where she and Adrian Gordon had kissed with lips that were quick and kind. Well, he had spoken the truth when he said she would have but a poor wedding-day!

She crept home at last, white as her cotton gown. With only one thought—to get unseen to her own room—she went into the house through the open window of the drawing-room, where no one ever sat. But to-day it was, for once, occupied.

Fairly inside the French window before she saw the two people in the room, she turned whiter than ever.

Lady Annesley, in her best tea-gown, drinking tea; and beside her, the low sun full on his handsome, sneering face, the strange man who had driven her home last evening. Ravenel, by instinct, put up her hand to cover her trembling lip. In her white gown, with her whiter face, she looked like a ghost as she stood staring.

Lord Levallion had the grace not to look at her as he came forward, and took her cold, indifferent hand. Lady Annesley put down her cup pettishly.

“Why do you never come in by the door like a Christian?” she said. “You quite startled me. Lord Levallion has come over to ask how you are—after yesterday!”

Lord Levallion? So this was he. Well, it was all one to her! There was only one man in all the world who mattered to Ravenel Annesley, and he had forsaken her. She turned to go, stumbling on the window-sill.

“Come and sit down. You look tired to death,” commanded Lady Annesley, and the taunt stung her stepdaughter. If her world had gone to pieces like a pack of cards, there was no reason that her ladyship should know it! She turned, sat down on the first chair she came to, and met Lord Levallion’s eyes turned on her curiously.

“Have you been walking? It’s too hot to walk,” he observed languidly. “I got up early this morning and took my exercise: rode over to have breakfast with Captain Gordon of the —— Hussars. Do you know him?”

Lady Annesley was livid in her fright. She had not dared confide in Levallion—and what was going to be the result?

“Yes, I know him,” Ravenel said evenly. She had her hat in her lap and was playing with the pin out of it.

“You know he went off to India to-day, then, by the first train for Southampton. I rather took him by surprise, for he left me in London. I can’t say I had a cheerful breakfast. Every one seemed so cast down at his leaving—but I enjoyed my ride.”

Thank God she could not get any paler! And the Annesleys were ever proud. This one, who was but a child and hurt to the heart, kept her face steady.

“Yes,” she said, and her voice sounded quite natural, for she heard it as though it were some one else’s. “Why? Was Captain Gordon dull?”

“Extremely noisy, on the contrary. Delighted, evidently, to be getting away.”

But she heard Levallion’s answer through the whirl of a hundred thoughts that seemed to sound and move in her head. Adrian had gone to India!—gone without a word of good-by, broken all his promises, forsaken her with a false, lying letter. Oh, Adrian, Adrian!

Desperately, like a savage, Ravenel stuck her steel hat-pin straight into her finger, and the sharp pain steadied her. She must not—dare not—think of him now. Whatever happened she must be brave before her ladyship and Levallion. And that wild cry at her heart was stifling her. Oh, Adrian—Adrian!

“What’s the matter? Have you cut your hand?” cried her stepmother shrilly. Levallion was no fool; he had probably put two and two together already! She was thankful to see a tangible reason for the girl’s strange pallor and quietude.

Ravenel nodded. Not for anything in the world could she have spoken without giving voice to that cry in her soul to Adrian Gordon, who was on the sea.

If Sylvia Annesley had known it, nothing else in the world would have so softened Lord Levallion’s heart to the girl she meant him to marry as the sight of her sitting pale as death and as proud.

“God! there’s stuff in the child!” he reflected swiftly. “And I’ll help her. Madam Sylvia’s been up to some low trick with her, I’ll lay my life!” but his voice was cooler than usual as he quietly cut off another question from that much-tried woman.

“That pin has gone through your finger, Miss Annesley,” he interposed quietly. “You should go at once and bathe it with hot water. They are nasty things—hat-pins,” and he rose composedly and opened the door for Ravenel to leave the room.

If any one had told her three days ago that she would ever have been grateful to Lord Levallion she would have laughed in their face. But now she looked at him as a caged bird might do when suddenly set free; like the bird, slipped through the door he had opened for her, dumb and dazed, but—thank God!—safe away from Sylvia’s eyes.

Lord Levallion returned to his seat.

“What have you been doing to that child, Sylvia?” he inquired harshly. “You have delicately suggested you would like me to marry her, but I warn you it is no use trying to force either her or me into it. If I want to marry her I shall, but it’s not any too likely. And the more you scheme the less I shall probably oblige you.”

“What makes you think anything so absurd?” angrily.

“My dear lady, I put two and two together. First, you write to me, and I have not heard from you for years. Then you are eager that I should meet the girl. Last, I come here, and find you poor—unbearably poor, for you! And a good marriage for the girl would mean a competence for you, and I am the only man you know with money. So you find out I am staying with the duchess, dress your lamb for the slaughter, and make her life miserable so that she will fly to my arms. Eh, Sylvia?” slowly.

Lady Annesley grew redder than her rouge. Levallion was too shrewd for once, and overshot himself. But it was better he should think Ravenel unhappy at home than suspect she was sick for the sight of Adrian Gordon.

“I—we—don’t get on! It is a grief to me,” she said prettily.

Levallion smiled. Any other man would have laughed outright; but he was not given to laughter. Fancy Sylvia—Sylvia!—scheming and match-making for him. It was better than any play. She had been clever, too, to have found out that he was thinking of marrying. He was forty-seven years old, and had no one to inherit either title or estates but his second cousin. If Lady Annesley had known her peerage better, she might have thought twice of meddling with Adrian Gordon’s love-affairs.

“I should advise you to try and get on—while I am here,” he broke the pause abruptly. “I do not like jars and tears.”

Lady Annesley trembled. She saw her dreams of Levallion’s country houses and a comfortable allowance—above all, a position as Lady Levallion’s mother—fading into thin air.

“The girl is dull here,” she said. “I can’t help it. She wants a change, I suppose, and I can’t give it to her.”

“Take her to town for a week.”

Her ladyship looked at him, her beautiful delicate face for once sincere.

“Walk there, camp in Piccadilly, walk home again!” she observed. “What a delightful program! That is the only way I could manage it.”

“Perhaps so,” returned Lord Levallion equably, and rose to go. He had his own thoughts on the subject, but as yet they did not burn to be made public. He meant to come over again before he went to town himself, but he did not mention that, either. He would not come to see Sylvia, nor did he wish to be considered her ally.

Sir Thomas Annesley, from a convenient post on the stairs, watched the visitor’s exit, and then repaired with haste to his sister’s room.

“Ravenel, let me in, I say!” he demanded, pounding on the door.

But he got no answer.

Ravenel, face down, lay on her bed convulsed with rage and shame to think that she should be crying herself sick for Adrian Gordon, who had left her like a dog he was tired of—left her with lying promises he had not cared to keep—and taken the best part of her with him.

“Ravenel, let me in, can’t you? I want to speak to you!” Sir Thomas’ persistent pounding reached her deaf ears at last.

She got up trembling and began to bathe her stained face with cold water.

“I can’t, Tommy! I—I’m washing,” she called out angrily.

“Well, hurry up and I’ll wait!”

Ravenel, sponge in hand, flung the door open.

“Come in and be done!” she cried. “What is it?”

Her face was blotched and patchy with crying, and the boy’s eyes kindled as he saw it.

“What’s that brute Levallion been saying to you?” he demanded. “And what’s Gordon gone off for like this?”

“He’s gone off because he’s sick of me; he’s thrown me over.” She spoke brutally. She was not going to gloss things over to Tommy. “And Lord Levallion hasn’t done anything. He’s the only decent person I know,” with which the door banged once more in Sir Thomas’ face.

Gordon sick of her—and Levallion decent! The boy was dumb with amazement. She would be praising her ladyship next. He went slowly away and sought Mr. Jacobs.

“My good dog,” he said disgustedly to that villainous animal, “there’s going to be trouble!”

A VERY CLEVER PERSON.

Lord Levallion and the Duchess of Avonmore sat at breakfast in the duchess’ own sitting-room. It was one of her habits seldom to breakfast with her guests, but to have one chosen companion at her own table. Avonmore was Liberty Hall since the death of the duke, who had not been exactly a comfortable partner for his handsome wife. She never allowed, even to herself, that she was happier without him, but the world knew it, as it knows everything unpublished.

She sat now in a Norfolk jacket and a short skirt, making an extensive breakfast. Since seven o’clock she had been tramping from her dairy to her hen walks, as thriftily as any farmer’s wife. But her handsome, weather-beaten face, with its shrewd, keen eyes, and her beautifully dressed white hair, made her look dignified, in spite of her short skirts and her full-blown figure.

Lord Levallion was drinking a cup of tea—very slowly—and looking at some dry toast with distaste. He had not been trudging in the morning air, and had had a bad night into the bargain. But the duchess and he were old friends, and he did not trouble himself to make conversation.

She shook her head at him as she saw his untouched breakfast.

“That’s not the way to get to a green old age, Levallion!” she observed as she took a second helping of bacon. “But I suppose it’s London habits that stick by you. Are you really off this morning?” He nodded.

“Surely you’re coming up again soon?” inquiringly, for she had been tempted into the country for a week by the perfect weather, and had stayed to give her yearly garden-party and get it over. “You will be losing the cream of things!

“I’m going up next week. To tell you the truth, Levallion, I feel lonely when I get to my town house and haven’t my dairy and my chickens to amuse me! It’s a big, desolate barrack, you know, and I hate it. If I’d had a daughter to bring out it might be different,” wistfully, “but without a chick or a child what are town parties to me?”

“Adopt one!” said Levallion, not unkindly.

The duchess shook her head.

“Too risky! But I thought of having some girl to stay with me, if I could find the right girl.”

“You’ve two nieces!” Levallion was clever; not a tone of his uninterested voice betrayed that he had an object in his idle talk.

“Odious brats!” returned the duchess sharply. They were the late duke’s nieces, not hers. “I couldn’t stand either of them for a day. The only girl I’ve seen and taken a fancy to is that nice-looking child of old Tom Annesley’s. But I don’t want to have any dealings with that yellow-haired stepmother of hers. I beg your pardon, Levallion! I forgot you were a friend of hers.”

Lord Levallion looked up, a curious expression on his pale, handsome face.

“You need not beg my pardon,” he said. “But I assure you Lady Annesley is—a very clever person!”

“She’s a detestable one!” retorted the duchess smartly. “And I don’t think those children have much of a life with her. I declare, you might have knocked me down with a feather when I saw the girl here in a decent gown the other day! Usually her clothes are disgraceful; last winter that woman used to let her go about blue with cold.” Her grace of Avonmore, being a duchess, did not trouble to talk like one, except to people she disliked. And she had a soft spot for Levallion, in spite of his record.

His lordship hid a grin in his teacup. So he had been correct in his little idea that it was for him Sylvia had prepared her lamb!

“Miss Annesley looked hopelessly unhappy in her fine clothes,” he said smoothly, “but extraordinarily handsome, in spite of her tears.” He pulled himself up sharply as if the last word had slipped out unawares.

“Tears!” The duchess stared at him. “What do you mean? I remember now. She never said good-by to me. I don’t like to think of Tom Annesley’s girl crying at my party. How do you know?”

“Saw her,” laconically. “Gave her some good advice and drove her home. She never spoke to me the whole way.”

A light dawned on the duchess.

“So that,” she observed slowly, “was where you went to! You’re not a good friend for any girl, Levallion, and I won’t have it with Tom’s daughter. Mind that! I shall drive over and see that child this afternoon. I’ve been a neglectful old woman not to have looked after her before.”

She pushed away her empty plate and got up. Levallion strolled meekly to the window, where he lit a cigarette. The duchess was a good woman, and Sylvia Annesley was—otherwise! But it was the latter who had discovered he was ready to marry and settle down at last. The duchess only remembered the women he had compromised; it never struck her that he might actually think of marrying a little country girl of eighteen. If it had, she would probably have put a spoke in his wheel; to have known Levallion for thirty years was not to envy his future countess.

Yet to marry Ravenel Annesley was the only thought the man had. The day before he had cleverly evaded Sylvia and paid an impromptu visit to Annesley Chase by the back gate; a piece of diplomacy for which he was rewarded by coming straight on Ravenel in the garden.

She was alone; her little chin had lifted angrily when she saw him, but the next moment she was ashamed. After all, he had been kind to her twice. She had nothing against him except that he was a friend of Sylvia’s.

Levallion was too wise to stay long, though there were no tears—and no hat-pins!—to-day. Her face was as cold as his lordship’s own, and her indifference more real. He might go or stay, as he liked—and he knew it.

But he carried away with him the memory of her strangely quiet face, uncannily, clearly pale as she walked up and down the garden paths.

“There goes Lady Levallion!” he thought, as certainly as if she stood by him at the altar. “And the sooner she is away from that devil Sylvia the better. Sylvia was always a genius at making people miserable, and the girl looks as though she beat her!”

In spite of his acuteness, he never thought—or, perhaps, would not have cared if he had—that another man had been the cause of that white face and somber eyes; nor that he himself had never seen the real Ravenel Annesley, all life and laughter, but only the ghost of a girl whose youth was dead in her. It annoyed him to fall in with Sylvia’s schemes, but, after all, that was a trifle; and he knew how to cut her claws a little. Therefore, with security and determination, Levallion laid siege to the duchess; and he smiled calmly as she bade good-by to him.

“Au revoir till next week,” he said, as they shook hands.

“Humph!” her grace coughed dryly. “I’ll send for you when I want you, my dear Levallion.”

Levallion chuckled when he got, rather stiffly, into the carriage. He was warned off. That meant Tom Annesley’s daughter was to be asked to Avonmore House. His lordship was more pleased than by a dozen cordial invitations.

The duchess, the instant his back was turned, proceeded to Annesley Chase in state, though she would far rather have gone on her bicycle. Lady Annesley was, providentially, out. Miss Annesley—Adams did not know.

“Then find out, my good girl,” remarked the duchess calmly sweeping by her into the house. She was not to be turned from Tom Annesley’s door by the servant of his twopenny second wife. “And fetch Sir Thomas,” majestically.

But Tommy had seen her coming and arrived hastily on the scene. He looked worried, and the duchess saw it.

“Where’s your sister, Tommy?” she said kindly.

The boy looked at her. She was the oldest friend they had, but even so, his sister’s secret was her own.

“She’s in the garden; she’s not very well,” he returned loyally. If Ravenel were fretting for Gordon there was no good in saying so. “Shall I call her for you?”

“Suppose we go to her!” slipping a stout arm through his. “Not well? What’s the matter with her?”

Tommy was appalled for one instant.

“Dyspepsia,” he said stoutly, with a flash of genius.

“Oh!” commented the duchess dryly. “Very like a whale in a butter-boat,” she added to herself, as she glanced at Ravenel, who rose from her knees in the garden as she heard the rustle of the duchess’ silk-lined skirts on the gravel.

“I beg your pardon for not coming in,” the girl faltered. “I thought you were Lady Annesley.” She looked doubtfully at her earthy hands and the visitor’s smart, white gloves.

The duchess, in spite of her parting words to Levallion, had not come with any definite purpose; but the sight of the girl’s white face and hard-set lips—more than all the glance of shuddering aversion she had given her, thinking she was her stepmother—brought a sudden rush of motherly tears to her kind, worldly-wise eyes.

“Never mind your hands!” she cried, sitting down on a wicker chair that creaked under her; “nor Lady Annesley either. I didn’t come to see her—I suppose there’s no one about to hear such treason!” with a hasty glance behind her. “I came to see you. I didn’t think you looked well the other day at my house”—really, the girl’s fresh beauty had astounded her—“and I came to ask you and Tommy to take pity on a lonely old woman and come to London with me for a month,” with a nod at the two which set the green and pink feathers on her smart bonnet wagging. “What do you say?”

“Oh, my eye—rather!” Sir Thomas forgot his manners in his joy. But the duchess was looking at Ravenel. She had not been prepared to see such a change in the pale, sick face.

To get away from Lady Annesley and the place that had grown hateful to her for a whole month—she and Tommy! A slow red burned into her cheeks at the thought, but a second after her face fell again. She could not go; she had no clothes fit to wear. Tommy was different; a boy did not matter. But she herself had not so much as a decent pair of gloves to wear up in the train.

“We—that is, I can’t!” she blurted out miserably.

“Why not? Because you’ve nothing to wear?” shrewdly.

“No!” with no truth and a red face, for her old friend must not think she was begging. “I just can’t.”

“Do you want to come?” slowly.

No answer. The girl’s lip was trembling at the kindness of the motherly voice.

The duchess looked at her.

“You do! Then that’s all right,” cheerfully. “As for gowns, I mean to give you those. I haven’t got any one to spend my money on except some horrid chits of nieces who don’t need it. That will be half the pleasure of having you. And I’ll settle it with your stepmother.”

But Ravenel was crying—sobbing from her sick heart against the duchess’ smart shoulder.

“My dear, I know,” said that soft-hearted lady incoherently, muttering to herself things about “that woman, who did not know how to treat Tom’s child.” And she had, like Levallion before her, never an inkling of Adrian Gordon’s part in the play.

HER LADYSHIP SHUFFLES THE CARDS.

Lady Annesley sat in speechless fury over the note that arrived from the duchess the very next morning.

About her was spread her whole wardrobe, which she had been looking over with the eye of a born milliner, quite certain that Levallion’s hints about London had meant he would give her the money to take Ravenel there. And this—with a vicious glance at the duchess’ letter—was their real meaning!

“For, of course, it’s all Levallion!” She drummed angrily on her knee with slim, white fingers. “I have half a mind to checkmate him. He might, considering everything, have sent me to town. But for me he never would have seen his pink-and-white doll.”

She threw the duchess’ letter on a table, where it hit a pile of other letters—blue enveloped, ominous—and sent them rustling to the floor. They were merely the quarter’s bills from the butcher and the wine-merchant for those luxuries Sylvia Annesley could never deny herself, but she picked them up with a vicious hand.

“It’s well for you, Levallion, that I haven’t a penny to pay these, or you might whistle for my lovely stepdaughter!” she said aloud. “But I can’t stand five more years like this before Tom comes of age. Five more years of dulness, of skimping, without a soul to speak to, and then the prospect of turning out of this and living on nothing a week in lodgings—no! it’s not to be done!”

She went to the glass and looked at herself feverishly, pushing back her curled golden hair from her temples, dragging up the blinds till the unkind daylight made her look every hour of her age.

“I’m getting old—old and hideous!” she stamped with passion. “I who love youth and good looks and life. Why did I ever bury myself here with the old fool who’s dead? Oh, I want to go out into the world again—to live! To dine, dress, and gamble, to make fools of men—that is life. And that girl’s marriage to Levallion is the only way I shall ever see it again. He shall marry her if I have to swallow my pride ten times over. He’d have to give me an allowance that would not disgrace Lady Levallion’s mother! Ravenel shall go to the duchess; Levallion will take care no other man gets a chance at her”—in spite of her rage with him, she was secure in her old knowledge of his cleverness—“and I will stay here and try to help things on!” with a pale smile.

She went to the door and locked it, then to her dressing-case and dragged out a photograph. For a minute she stood and stared at it, biting her lips.

“I can’t do anything with it,” she thought angrily. “And I daren’t trust any one—but——” With swift inspiration a thought had come to her.

“Hester Murray!” she cried half-aloud. “Hester can tell her a bit of—truth! The silly old duchess will never imagine that Hester and I are old acquaintances—Hester, who runs in and out of Avonmore to help me; if she doesn’t I’ll make an unpleasant squall in the Murray mansion. This match-making,” with a little laugh, “is most amusing.”

Her ill humor gone utterly, she sat down at her writing-table and constructed a letter to make her old friend shake in her shoes, in spite of its affection. She sealed up her letter and the photograph, for Hester might not have one, and then turned her attention to something else.

“I have a great mind to get rid of Adams,” she thought. “She is getting beyond herself. But I’ll wait a little; she might talk. And, after all, ‘better a devil you know than a devil you don’t know’!” forcibly. “Though I doubt if Hester will think so,” with a curious look, as if something had come back from the past and pleased her.

“Well,” she said half-aloud, “I suppose the duchess will deck out my dear stepdaughter in purple and fine linen, but unless I want to look a beast, I suppose I ought to provide her with at least one gown. I, who haven’t two coins to rub together nowadays. She wouldn’t wear my clothes if I gave them to her, and I’ve no desire to part with them. I don’t care to interview her, either. She does hate me so!” for her ladyship’s wits at least were young still, whatever her eyes might be.

“I must do the best I can,” she said thoughtfully; and there alone in the little rose-colored room did a curious thing, for Lady Annesley, not for a woman who loved her dead husband’s child. She took a ruby ring from her finger and slipped it in a note quickly written and addressed to her stepdaughter. It was a simple little effort enough, saying merely that she had received from the duchess an invitation for Tom and Ravenel to spend a month with her in London and would accept for them with pleasure if they cared to go.

“As for gowns,” it ran, “I will do the best I can for you, but as that may be small just now, I send you this ring, which you can wear or turn into money, as you choose. It is one your father gave me. I would send for you to talk over your frocks, but my neuralgia is terrific to-day.”

She rang for Adams to deliver the note and waited for her to come back with a curious anxiety. It looked well to be generous, but she hated giving away her rubies. It seemed half a year before the maid returned with—yes—with a note!

Lady Annesley tore it open, and her strained lips grew triumphant. She had been generous at no cost whatever.

“Thank you very much”—Ravenel had written with furious haste, having no mind for any more of her ladyship’s gifts—“but I don’t want to keep your ring. I send it back in this. You had better wear it yourself.

“Ravenel.”

That was absolutely all. Lady Annesley slipped her recovered ring on her finger.

“You can go, Adams,” she said carelessly. But when she was alone she laughed a laugh that showed her gums.

“I’ll have my house in town,” she gasped. “You’re a clever man, Levallion, but you’ll never know who is helping me to get you married. I’ll take care that you go on thinking me a fool. But to make Hester Murray help to get you—it’s too good!” She wiped her eyes where she sat helpless with laughter.

“Hester!” she murmured, “of all people.”

“A BIT OF THE TRUTH.”

The Duchess of Avonmore was worried.

She had carried her point and walked off Tom Annesley’s children to her big town house in Park Lane. She had given Ravenel such dresses as her own nieces would have sold their souls for, had done her best to make each day more pleasant than the last, and the only result was that one fine morning she sat alone with Ravenel, absolutely at a loss.

Sir Thomas was perfectly happy, new clothes and a horse to ride having made his countenance to shine as the sun. But Ravenel! the poor duchess sighed.

The girl was pathetically grateful for the benefits showered on her, and showed a clinging affection for the duchess that came near to bringing the tears to that good woman’s eyes; but there was no happiness in her face. She went everywhere; she was gay as if by an effort that sapped her strength, for each day she grew paler, her lovely lips more hard set. There was neither elation nor triumph in her eyes when women envied her or men admired her.

“Most girls would be off their heads with pleasure,” reflected the duchess. “That woman must have broken her spirit somehow. I wish I could find out what ails her.”

Tommy could have enlightened her, but he had been sworn to keep his mouth shut. And in the dark the poor duchess did the very worst thing possible.

“Ravenel,” she said cheerfully, “here’s an invitation for you. Mrs. Murray wants you to lunch with her to-day. She is a great friend of mine—poor little woman! She will cheer you up.”

“I don’t need it,” with a grateful glance. She would rather have stayed with Tommy, but the duchess did not like her plans gainsaid.

Ravenel, getting out of the carriage at the door of Mrs. Murray’s small house in Eaton Place, stood on the doorstep just long enough for her pale-pink gown to catch the eye of a man lounging at a window in the opposite house.

“Humph!” said Lord Levallion curiously, “what’s the meaning of this? Nothing, I suppose, but that Grace Avonmore’s an idiot!”

He watched the girl in and rang for his servant.

“I’ll lunch up here, Lacy,” he said curtly, “and I’m not at home to visitors.”