PLATE I

THE DEPARTURE FOR THE SABBAT.

David Teniers

[frontispiece

Title: The history of witchcraft and demonology

Author: Montague Summers

Release date: October 28, 2025 [eBook #77145]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[i]

The History of Civilization

Edited by C. K. Ogden, M.A.

The History of Witchcraft

[ii]

The History of Civilization

Edited by C. K. Ogden, M.A.

Harry Elmer Barnes, Ph.D., Consulting American Editor.

| The volumes already published are: | |

| *Social Organization | W. H. R. Rivers, F.R.S. |

| *A Thousand Years of the Tartars | Professor E. H. Parker |

| *The Threshold of the Pacific | Dr. C. E. Fox |

| The Earth Before History | Edmond Perrier |

| Prehistoric Man | Jacques de Morgan |

| Language | Professor J. Vendryes |

| *History and Literature of Christianity | Professor P. de Labriolle |

| *China and Europe | Adolf Reichwein |

| *London Life in the Eighteenth Century | M. Dorothy George |

| A Geographical Introduction to History | Professor Lucien Febvre |

| *The Dawn of European Civilization | V. Gordon Childe, B.Litt. |

| Mesopotamia: Babylonian and Assyrian Civilization | Prof. L. Delaporte |

| *The Ægean Civilization | Professor Gustave Glotz |

| *The Peoples of Asia | L. H. Dudley Buxton |

| *The Migration of Symbols | Donald A. Mackenzie |

| *Life and Work in Modern Europe | Professor Georges Renard |

| *Travel and Travellers of the Middle Ages | Edited by Prof. A. P. Newton |

| *Civilization of the South American Indians | Rafael Karsten |

| Race and History | Professor E. Pittard |

| From Tribe to Empire | Professor A. Moret |

| *A History of Witchcraft | Montague Summers |

| *Ancient Greece at Work | Professor G. Glotz |

| The Formation of the Greek People | Professor A. Jardé |

| *The Aryans | V. Gordon Childe, D.Litt. |

| Primitive Italy | Professor Léon Homo |

| Rome the Law-Giver | Professor J. Declareuil |

| The Roman Spirit | Professor A. Grenier |

| In preparation: | |

| *Life and Work in Medieval Europe | Professor Boissonade |

| *A History of Medicine | C. G. Cumston, M.D. |

| Ancient Persia and Iranian Civilization | Professor C. Huart |

| *Ancient Rome at Work | Paul Louis |

| The Life of Buddha | E. H. Thomas, D.Litt. |

* An asterisk indicates that the volume does not form part of the French collection “L’Évolution de l’Humanité.”

A complete classified list of the Series will be found at the end of this volume.

PLATE I

THE DEPARTURE FOR THE SABBAT.

David Teniers

[frontispiece

[iii]

The History of Witchcraft and

Demonology

By

MONTAGUE SUMMERS

NEW YORK

ALFRED A. KNOPF

1926

[iv]

To

PATRICK,

in memory of Loreto and Our Lady’s Holy House, as also of Our Lady’s miraculous Picture at Campocavallo, Our Lady of Pompeii, La Consolata of Turin, Consolatrix Afflictorum in S. Caterina ai Funari at Rome, la Santissima Vergine del Parto of S. Agostino, the Madonna della Strada at the Gesù, La Nicopeja of San Marco at Venice, Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle of Rennes, Notre-Dame de Grande Puissance of Lamballe, and all the Italian and French Madonnas at whose shrines we have worshipped.

Printed in Great Britain at

The Mayflower Press, Plymouth. William Brendon & Son, Ltd.

[v]

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | vii | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | The Witch: Heretic and Anarchist | 1 |

| II. | The Worship of the Witch | 51 |

| III. | Demons and Familiars | 81 |

| IV. | The Sabbat | 110 |

| V. | The Witch in Holy Writ | 173 |

| VI. | Diabolic Possession and Modern Spiritism | 198 |

| VII. | The Witch in Dramatic Literature | 276 |

| Bibliography | 315 | |

| Index | 347 |

[vi]

| PLATE | ||

| I. | The Departure for the Sabbat (David Teniers) | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | ||

| II. | The World Tost at Tennis. 4to., 1620 | 8 |

| (Facsimile title-page.) | ||

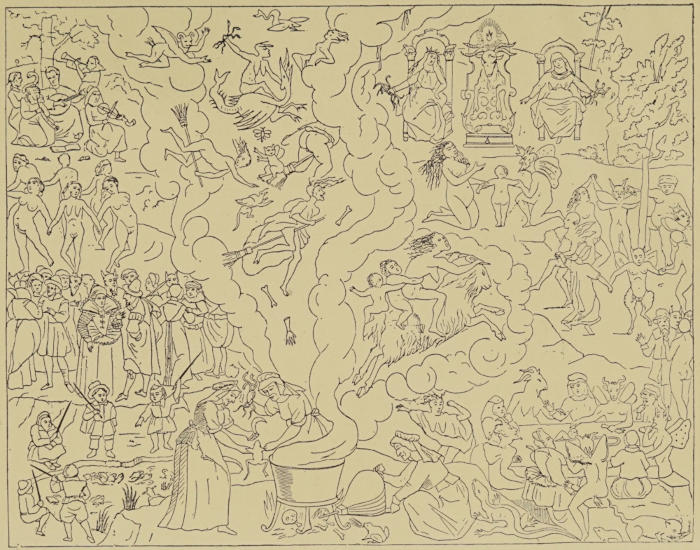

| III. | Compendivm Maleficarvm. Mediolani, 1626 | 82 |

| (Facsimile title-page of second edition.) | ||

| IV. | Off to the Sabbat (Queverdo) | 120 |

| V. | The Sabbat (Ziarnko) | 144 |

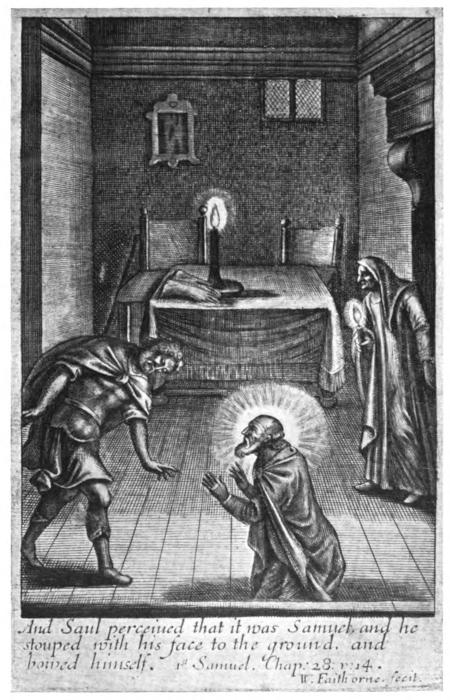

| VI. | The Witch of Endor (W. Faithorne) | 178 |

| (Frontispiece to Sadducismus Triumphatus, 1681) | ||

| VII. | S. James Visits the Warlock’s Den (Pieter Breughel) | 250 |

| VIII. | The Witch of Edmonton. 4to., 1658 | 290 |

| (Facsimile title-page.) |

[vii]

The history of Witchcraft, a subject as old as the world and as wide as the world,—since I understand for the present purpose by Witchcraft, Sorcery, Black Magic, Necromancy, secret Divination, Satanism, and every kind of malign occult art,—at once confronts the writer with a most difficult problem. He is called upon to exercise a choice, and his dilemma is by no means made the easier owing to the fact he is acutely conscious that whichever way he may decide he is laying himself open to damaging and not impertinent criticism. Since it is essential that his work should be comprised within a reasonable compass he may elect to attempt a bird’s-eye view of the whole range from China to Peru, from the half-articulate, rhythmic incantations of primitive man at the dawn of life to the last spiritistic fad and manifestation at yesterday’s séance or circle, in which case his pages will most certainly be thin and often superficial: or again he may rather concentrate upon one or two features in the history of Witchcraft, deal with these at some length, stress some few forgotten facts whose importance is now neglected and unrealized, utilize new material the result of laborious research, but all this at the expense of inevitable omissions, of hiatus, of self-denial, the avoidance of fascinating by-ways and valuable inquiry, of silence when he would fain be entering upon discussion and exposition. With a full sense of its drawbacks and danger I have selected the second method, since in dealing with a topic such as Witchcraft where there is no human hope of recording more than a tithe of the facts I believe it is better to give a documented account of certain aspects rather than to essay a somewhat huddled and confused conspectus of the whole, for such, indeed, even at best is itself bound to have no inconsiderable gaps and lacunæ, however carefully we endeavour to make it complete. I am conscious, then, that there is scarcely a paragraph in the present work which might not easily be [viii]expanded into a page, scarcely a page which might not to its great advantage become a chapter, and certainly not a chapter that would not be vastly improved were it elaborated to a volume.

Many omissions are, as I have said, a necessary consequence of the plan I have adopted; or, indeed, I venture to suppose, of any other plan which contemplates the treatment of so universal a subject as Witchcraft. I can but offer my apologies to these students who come to this History to find details of Finnish magic and the sorceries of Lapland, who wish to inform themselves concerning Tohungaism among the Maoris, Hindu devilry and enchantments, the Bersekir of Iceland, Siberian Shamanism, the blind Pan Sus and Mutangs of Korea, the Chinese Wu-po, Serbian lycanthropy, negro Voodoism, the dark lore of old Scandinavia and Islam. I trust my readers will believe that I regret as much as any the absence of these from my work, but after all in any human endeavour there are practical limitations of space.

In a complementary and companion volume I am intending to treat the epidemic of Witchcraft in particular localities, the British Isles, France, Germany, Italy, New England, and other countries. Many famous cases, the Lancashire witch-trials, the activities of Matthew Hopkins, Gilles de Rais, Gaufridi, Urbain Grandier, Cotton Mather and the Salem sorceries, will then be dealt with and discussed in some detail.

It is a surprising fact that amongst English writers Witchcraft in Europe has not of recent years received anything like adequate attention from serious students of history, who strangely fail to recognize the importance of this tragic belief both as a political and a social factor. Magic, the genesis of magical cults and ceremonies, the ritual of primitive peoples, traditional superstitions, and their ancillary lore, have been made the subject of vast and erudite studies, mostly from an anthropological and folk-loristic point of view, but the darker side of the subject, the history of Satanism, seems hardly to have been attempted.

Possibly one reason for this neglect and ignorance lies in the fact that the heavy and crass materialism, which was so prominent a feature during the greater part of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in England, intellectually disavowed the supernatural, and attempted not without some [ix]success to substitute for religion a stolid system of respectable morality. Since Witchcraft was entirely exploded it would, at best, possess merely an antiquarian interest, and even so, the exhumation of a disgusting and contemptible superstition was not to be encouraged. It were more seemly to forget the uglier side of the past. This was the attitude which prevailed for more than a hundred and fifty years, and when Witchcraft came under discussion by such narrowly prejudiced and inefficient writers as Lecky or Charles Mackay they are not even concerned to discuss the possibility of the accounts given by the earlier authorities, who, as they premise, were all mistaken, extravagant, purblind, and misled. The cycle of time has had its revenge, and this rationalistic superstition is dying fast. The extraordinary vogue of and immense adherence to Spiritism would alone prove that, whilst the widespread interest that is taken in mysticism is a yet healthier sign that the world will no longer be content to be fed on dry husks and the chaff of straw. And these are only just two indications, and by no means the most significant, out of many.

It is quite impossible to appreciate and understand the true lives of men and women in Elizabethan and Stuart England, in the France of Louis XIII and his son, in the Italy of the Renaissance and the Catholic Reaction—to name but three countries and a few definite periods—unless we have some realization of the part that Witchcraft played in those ages amid the affairs of these kingdoms. All classes were concerned from Pope to peasant, from Queen to cottage gill.

Accordingly as actors are “the abstracts and brief chronicles of the time” I have given a concluding chapter which deals with Witchcraft as seen upon the stage, mainly concentrating upon the English theatre. This review has not before been attempted, and since Witchcraft was so formidable a social evil and so intermixed with all stations of life it is obvious that we can find few better contemporary illustrations of it than in the drama, for the playwright ever had his finger upon the public pulse. Until the development of the novel it was the theatre alone that mirrored manners and history.

There are many general French studies of Witchcraft of [x]the greatest value, amongst which we may name such standard works as Antoine-Louis Daugis, Traité sur la magie, le sortilège, les possessions, obsessions et maléfices, 1732; Jules Garinet, Histoire de la Magie en France depuis le commencement de la monarchie jusqu’à nos jours, 1818; Michelet’s famous La Sorcière; Alfred Maury, La Magie et l’Astrologie, 3rd edition, 1868; L’Abbé Lecanu, Histoire de Satan; Jules Baissac, Les grands Jours de la Sorcellerie, 1890; Theodore de Cauzons, La Magie et la Sorcellerie en France, 4 vols., 1910, etc.

In German we have Eberhard Hauber’s Bibliotheca Magica; Roskoff’s Geschichte des Teufels, 1869; Soldan’s Geschichte der Hexenprozesse (neu bearbeitet von Dr. Heinrich Heppe), 1880; Friedrich Leitschuch’s Beitræge zur Geschichte des Hexenwesens in Franken, 1883; Johan Dieffenbach’s Der Hexenwahn vor und nach der Glaubensspaltung in Deutschland, 1886; Schreiber’s Die Hexenprozesse im Breisgau; Ludwig Rapp’s Die Hexenprozesse und ihre Gegner aus Tirol; Joseph Hansen’s Quellen und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte des Hexenwahns, 1901; and very many more admirably documented studies.

In England the best of the older books must be recommended with necessary reservations. Thomas Wright’s Narratives of Sorcery and Magic, 2 vols., 1851, is to be commended as the work of a learned antiquarian who often referred to original sources, but it is withal sketchy and can hardly satisfy the careful scholar. Some exceptionally good writing and sound, clear, thinking are to be met with in Dr. F. G. Lee’s The Other World, 2 vols., 1875; More Glimpses of the World Unseen, 1878; Glimpses in the Twilight, 1885; and Sight and Shadows, 1894, all of which deserve to be far more widely known, since they well repay an unhurried and repeated perusal.

Quite recent work is represented by Professor Wallace Notestein’s History of Witchcraft in England from 1558 to 1718, published in 1911. This intimate study of a century and a half concentrates, as its title tells, upon England alone. It is supplied with ample and useful appendixes. In respect of the orderly marshalling of his facts, garnered from the trials and other sources—no small labour—Professor Notestein deserves a generous meed of praise; his interpretation [xi]of the facts and his deductions may not unfairly be criticized. Although his incredulity must surely now and again be shaken by the cumulative force of reiterated and corroborative evidence, nevertheless he refuses to admit even the possibility that persons who at any rate affected supernatural powers held clandestine meetings after nightfall in obscure and lonely places for purposes and plots of their own. If human testimony is worth anything at all, unless we are to be more Pyrrhonian than the famous Dr. Marphurius himself who would never say, “Je suis venu; mais; Il me semble que je suis venu,” when in 1612 Roger Nowell had swooped down on the Lancashire coven and carried off Elizabeth Demdike with three other beldames to durance vile in Lancaster Castle, Elizabeth Device summoned the whole Pendle gang to her home at Malking Tower, in order that they might discuss the situation and contrive the delivery of the prisoners. As soon as they had forgathered, they all sat down to dinner, and had a good north country spread of beef, bacon, and roast mutton. Surely there is nothing very remarkable in this; and the evidence as given in Thomas Potts’ famous narrative, The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the countie of Lancaster (London, 1613), bears the very hall-mark and impress of truth: “The persons aforesaid had to their dinners Beefe, Bacon, and roasted Mutton; which Mutton (as this Examinates said brother said) was of a Wether of Christopher Swyers of Barley: which Wether was brought in the night before into this Examinates mothers house by the said Iames Deuice, the Examinates said brother: and in this Examinates sight killed and eaten.” But Professor Notestein will none of it. He writes: “The concurring evidence in the Malking Tower story is of no more compelling character than that to be found in a multitude of Continental stories of witch gatherings which have been shown to be the outcome of physical or mental pressure and of leading questions. It seems unnecessary to accept even a substratum of fact” (p. 124). In the face of such sweeping and dogmatic assertion mere evidence is no use at all. For we know that the Continental stories of witch gatherings are with very few exceptions the chronicle of actual fact. It must be confessed that such feeble scepticism, which repeatedly mars his summary of the witch-trials, is a serious [xii]blemish in Professor Notestein’s work, and in view of his industry much to be regretted.

Miss M. A. Murray does not for a moment countenance any such summary dismissal and uncritical rejection of evidence. Her careful reading of the writers upon Witchcraft has justly convinced her that their statements must be accepted. Keen intelligences and shrewd investigators such as Gregory XV, Bodin, Guazzo, De Lancre, D’Espagnet, La Reynie, Boyle, Sir Matthew Hale, Glanvill, were neither deceivers nor deceived. The evidence must stand, but as Miss Murray finds herself unable to admit the logical consequence of this, she hurriedly starts away with an arbitrary, “the statements do not bear the construction put upon them,” and in The Witch-Cult in Western Europe (1921) proceeds to develop a most ingenious, but, as I show, a wholly untenable hypothesis. Accordingly we are not surprised to find that many of the details Miss Murray has collected in her painstaking pages are (no doubt unconsciously) made to square with her preconceived theory. However much I may differ from Miss Murray in my outlook, and our disagreement is, I consider, neither slight nor superficial, I am none the less bound to commend her frank and courageous treatment of many essential particulars which are all too often suppressed, and in consequence a false and counterfeit picture has not unseldom been drawn.

So vast a literature surrounds modern Witchcraft, for frankly such is Spiritism in effect, that it were no easy task to mention even a quota of those works which seem to throw some real light upon a complex and difficult subject. Among many which I have found useful are Surbled, Spiritualisme et spiritisme and Spirites et médiums; Gutberlet, Der Kampf um die Seele; Dr. Marcel Viollet, Le spiritisme dans ses rapports avec la folie; J. Godfrey Raupert, Modern Spiritism and Dangers of Spiritualism; the Very Rev. Alexis Lépicier, O.S.M., The Unseen World; the Rev. A. V. Miller, Sermons on Modern Spiritualism; Lapponi, Hypnotism and Spiritism; the late Monsignor Hugh Benson’s Spiritualism (The History of Religions); Elliot O’Donnell’s The Menace of Spiritualism; and Father Simon Blackmore’s Spiritism: Facts and Frauds, 1925. My own opinion of this movement has been formed not only from reading studies and monographs [xiii]which treat of every phase of the question from all points of view, but also by correspondence and discussion with ardent devotees of the cult, and, not least, owing to the admissions and warnings of those who have abandoned these dangerous practices, revelations made in such circumstances, however, as altogether to preclude even a hint as to their definite import and scope.

The History of Witchcraft is full of interest to the theologian, the psychologist, the historian, and cannot be ignored. But it presents a very dark and terrible aspect, the details of which in the few English studies that claim serious attention have almost universally been unrecorded, and, indeed, deliberately burked and shunned. Such treatment is unworthy and unscholarly to a degree, reprehensible and dishonest.

The work of Professor Notestein, for example, is gravely vitiated, owing to the fact that he has completely ignored the immodesty of the witch-cult and thus extenuated its evil. He is, indeed, so uncritical, I would even venture to say so unscholarly, as naïvely to remark (p. 300): “No one who has not read for himself can have any notion of the vile character of the charges and confessions embodied in the witch pamphlets. It is an aspect of the question which has not been discussed in these pages.” Such a confession is amazing. One cannot write in dainty phrase of Satanists and the Sabbat. However loathly the disease the doctor must not hesitate to diagnose and to probe. This ostrich-like policy is moral cowardice. None of the Fathers and great writers of the Church were thus culpably prudish. When S. Epiphanius has to discuss the Gnostics, he describes in detail their abominations, and pertinently remarks: “Why should I shrink from speaking of the things you do not fear to do? By speaking thus, I hope to fill you with horror of the turpitudes you commit.” And S. Clement of Alexandria says: “I am not ashamed to name the parts of the body wherein the fœtus is formed and nourished; and why, indeed, should I be, since God was not ashamed to create them?”

A few authors have painted the mediæval witch in pretty colours on satin. She has become a somewhat eccentric but kindly old lady, shrewd and perspicacious, with a knowledge of healing herbs and simples, ready to advise and aid her [xiv]neighbours who are duller-witted than she; not disdaining in return a rustic present of a flitch, meal, a poult or eggs from the farm-yard. And so for no very definite reason she fell an easy prey to fanatic judges and ravening inquisitors, notoriously the most ignorant and stupid of mortals, who caught her, swum her in a river, tried her, tortured her, and finally burned her at the stake. Many modern writers, more sceptical still, frankly relegate the witch to the land of nursery tales and Christmas pantomime; she never had any real existence other than as Cinderella’s fairy godmother or the Countess D’Aulnoy’s Madame Merluche.

I have even heard it publicly asserted from the lecture platform by a professed student of the Elizabethan period that the Elizabethans did not, of course, as a matter of fact believe in Witchcraft. It were impossible to imagine that men of the intellectual standard of Shakespeare, Ford, Jonson, Fletcher, could have held so idle a chimæra, born of sick fancies and hysteria. And his audience acquiesced with no little complacency, pleased to think that the great names of the past had been cleared from the stigma of so degrading and gross a superstition. A few uneducated peasants here and there may have been morbid and ignorant enough to dream of witches, and the poets used these crones and hags with effect in ballad and play. But as for giving any actual credence to such fantasies, most assuredly our great Elizabethans were more enlightened than that! And, indeed, Witchcraft is a phase of and a factor in the manners of the seventeenth century, which in some quarters there seems a tacit agreement almost to ignore.

All this is very unhistorical and very unscientific. In the following pages I have endeavoured to show the witch as she really was—an evil liver; a social pest and parasite; the devotee of a loathly and obscene creed; an adept at poisoning, blackmail, and other creeping crimes; a member of a powerful secret organization inimical to Church and State; a blasphemer in word and deed; swaying the villagers by terror and superstition; a charlatan and a quack sometimes; a bawd; an abortionist; the dark counsellor of lewd court ladies and adulterous gallants; a minister to vice and inconceivable corruption; battening upon the filth and foulest passions of the age.

[xv]

My present work is the result of more than thirty years’ close attention to the subject of Witchcraft, and during this period I have made a systematic and intensive study of the older demonologists, as I am convinced that their first-hand evidence is of prime importance and value, whilst since their writings are very voluminous and of the last rarity they have universally been neglected, and are allowed to accumulate thick dust undisturbed. They are, moreover, often difficult to read owing to technicalities of phrase and vocabulary. Among the most authoritative I may cite a few names: Sprenger (Malleus Maleficarum); Guazzo; Bartolomeo Spina, O.P.; John Nider, O.P.; Grilland; Jerome Mengo; Binsfeld; Gerson; Ulrich Molitor; Basin; Murner; Crespet; Anania; Henri Boguet; Bodin; Martin Delrio, S.J.; Pierre le Loyer; Ludwig Elich; Godelmann; Nicolas Remy; Salerini; Leonard Vair; De Lancre; Alfonso de Castro; Sebastian Michaelis, O.P.; Sinistrari; Perreaud; Dom Calmet; Sylvester Mazzolini, O.P. (Prierias). When we supplement these by the judicial records and the legal codes we have an immense body of material. In all that I have written I have gone to original sources, and it has been my endeavour fairly to weigh and balance the evidence, to judge without heat or prejudice, to give the facts and the comment upon them with candour, sincerity, and truth. At the same time I am very well aware that several great scholars for whom I have the sincerest personal regard and whose attainments I view with a very profound respect will differ from me in many particulars.

I am conscious that the rough list of books which I have drawn up does not deserve to be dignified with the title, Bibliography. It is sadly incomplete, yet should it, however inadequate, prove helpful in the smallest way it will have justified its inclusion. I may add that my Biblical quotations, save where expressly otherwise noted, are from the Vulgate or its translation into English commonly called the Douai Version.

In Festo S. Tereseiæ, V.

1925.

[1]

“Sorcier est celuy qui par moyens Diaboliques sciemment s’efforce de paruenir a quel que chose.” (“A sorcerer is one who by commerce with the Devil has a full intention of attaining his own ends.”) With these words the profoundly erudite jurisconsult Jean Bodin, one of the acutest and most strictly impartial minds of his age, opens his famous De la Demonomanie des Sorciers,[1] and it would be, I imagine, hardly possible to discover a more concise, exact, comprehensive, and intelligent definition of a Witch. The whole tremendous subject of Witchcraft, especially as revealed in its multifold and remarkable manifestations throughout every district of Southern and Western Europe from the middle of the thirteenth until the dawn of the eighteenth century,[2] has it would seem in recent times seldom, if ever, been candidly and fairly examined. The only sound sources of information are the contemporary records; the meticulously detailed legal reports of the actual trials; the vast mass of pamphlets which give eye-witnessed accounts of individual witches and reproduce evidence uerbatim as told in court; and, above all, the voluminous and highly technical works of the Inquisitors and demonologists, holy and reverend divines, doctors utriusque iuris, hard-headed, slow, and sober lawyers,—learned men, scholars of philosophic mind, the most honourable names in the universities of Europe, in the forefront of literature, science, politics, and culture; monks who kept the conscience of kings, pontiffs; whose word would [2]set Europe aflame and bring an emperor to his knees at their gate.

It is true that Witchcraft has formed the subject of a not inconsiderable literature, but it will be found that inquirers have for the most part approached this eternal and terrible chapter in the history of humanity from biassed, although wholly divergent, points of view, and in consequence it is often necessary to sift more or less thoroughly their partial presentation of their theme, to discount their unwarranted commentaries and illogical conclusions, and to get down in time to the hard bed-rock of fact.

In the first place we have those writings and that interest which may be termed merely antiquarian. Witchcraft is treated as a curious by-lane of history, a superstition long since dead, having no existence among, nor bearing upon, the affairs of the present day. It is a field for folk-lore, where one may gather strange flowers and noxious weeds. Again, we often recognize the romantic treatment of Witchcraft. ’Tis the Eve of S. George, a dark wild night, the pale moon can but struggle thinly through the thick massing clouds. The witches are abroad, and hurtle swiftly aloft, a hideous covey, borne headlong on the skirling blast. In delirious tones they are yelling foul mysterious words as they go: “Har! Har! Har! Altri! Altri!” To some peak of the Brocken or lonely Cevennes they haste, to the orgies of the Sabbat, the infernal Sacraments, the dance of Acheron, the sweet and fearful fantasy of evil, “Vers les stupres impurs et les baisers immondes.”[3] Hell seems to vomit its foulest dregs upon the shrinking earth; a loathsome shape of obscene horror squats huge and monstrous upon the ebon throne; the stifling air reeks with filth and blasphemy; faster and faster whirls the witches’ lewd lavolta; shriller and shriller the cornemuse screams; and then a wan grey light flickers in the Eastern sky; a moment more and there sounds the loud clarion of some village chanticleer; swift as thought the vile phantasmagoria vanishes and is sped, all is quiet and still in the peaceful dawn.

But both the antiquarian and the romanticist reviews of Witchcraft may be deemed negligible and impertinent so far as the present research is concerned, however entertaining and picturesque such treatment proves to many readers, [3]affording not a few pleasant hours, whence they are able to draw highly dramatic and brilliantly coloured pictures of old time sorceries, not to be taken too seriously, for these things never were and never could have been.[4]

The rationalist historian and the sceptic, when inevitably confronted with the subject of Witchcraft, chose a charmingly easy way to deal with these intensely complex and intricate problems, a flat denial of all statements which did not fit, or could not by some means be squared with, their own narrow prejudice. What matter the most irrefragable evidence, which in the instance of any other accusation would unhesitatingly have been regarded as final. What matter the logical and reasoned belief of centuries, of the most cultured peoples, the highest intelligences of Europe? Any appeal to authority is, of course, useless, as the sceptic repudiates all authority—save his own. Such things could not be. We must argue from that axiom, and therefore anything which it is impossible to explain away by hallucination, or hysteria, or auto-suggestion, or any other vague catch-word which may chance to be fashionable at the moment, must be uncompromisingly rejected, and a note of superior pity, to candy the so suave yet crushingly decisive judgement, has proved of great service upon more occasions than one. Why examine the evidence? It is really useless and a waste of time, because we know that the allegations are all idle and ridiculous; the “facts” sworn to by innumerable witnesses, which are repeated in changeless detail century after century in every country, in every town, simply did not take place. How so absolute and entire falsity of these facts can be demonstrated the sceptic omits to inform us, but we must unquestioningly accept his infallible authority in the face of reason, evidence, and truth.

Yet supposing that with clear and candid minds we proceed carefully to investigate this accumulated evidence, to inquire into the circumstances of a number of typical cases, to compare the trials of the fifteenth century in France with the trials of the seventeenth century in England, shall we not find that amid obvious accretions of fantastic and superfluous detail a certain very solid substratum of a permanent and invaried character is unmistakably to be traced throughout the whole? This cannot in reason be denied, and here we [4]have the core and the enduring reality of Witchcraft and the witch-cult throughout the ages.

There were some gross superstitions; there were some unbridled imaginations; there was deception, there was legerdemain; there was phantasy; there was fraud; Henri Boguet seems, perhaps, a trifle credulous, a little eager to explain obscure practices by an instant appeal to the supernormal; Brother Jetzer, the Jacobin of Berne, can only have been either the tool of his superiors or a cunning impostor; Matthew Hopkins was an unmitigated scoundrel who preyed upon the fears of the Essex franklins whilst he emptied their pockets; Lord Torphichen’s son was an idle mischievous boy whose pranks not merely deluded both his father and the Rev. Mr. John Wilkins, but caused considerable mystification and amaze throughout the whole of Calder; Anne Robinson, Mrs. Golding’s maid, and the two servant lasses of Baldarroch were prestidigitators of no common sleight and skill; and all these examples of ignorance, gullibility, malice, trickery, and imposture might easily be multiplied twenty times over and twenty times again, yet when every allowance has been made, every possible explanation exhausted, there persists a congeries of solid proven fact which cannot be ignored, save indeed by the purblind prejudice of the rationalist, and cannot be accounted for, save that we recognize there were and are individuals and organizations deliberately, nay, even enthusiastically, devoted to the service of evil, greedy of such emotions and experiences, rewards the thraldom of wickedness may bring.

The sceptic notoriously refuses to believe in Witchcraft, but a sanely critical examination of the evidence at the witch-trials will show that a vast amount of the modern vulgar incredulity is founded upon a complete misconception of the facts, and it may be well worth while quite briefly to review and correct some of the more common objections that are so loosely and so repeatedly maintained. There are many points which are urged as proving the fatuous absurdity and demonstrable impossibility of the whole system, and yet there is not one of these phenomena which is not capable of a satisfactory, and often a simple, elucidation. Perhaps the first thought of a witch that will occur to the man in the street is that of a hag on a broomstick flying up the chimney [5]through the air. This has often been pictorially impressed on his imagination, not merely by woodcuts and illustrations traditionally presented in books, but by the brush of great painters such as Queverdo’s Le Départ au Sabbat, Le Départ pour le Sabbat of David Teniers, and Goya’s midnight fantasies. The famous Australian artist, Norman Lindsay, has a picture To The Sabbat[5] where witches are depicted wildly rushing through the air on the backs of grotesque pigs and hideous goats. Shakespeare, too, elaborated the idea, and “Hover through the fog and filthy air” has impressed itself upon the English imagination. But to descend from the airy realms of painting and poetry to the hard ground of actuality. Throughout the whole of the records there are very few instances when a witness definitely asserted that he had seen a witch carried through the air mounted upon a broom or stick of any kind, and on every occasion there is patent and obvious exaggeration to secure an effect. Sometimes the witches themselves boasted of this means of transport to impress their hearers. Boguet records that Claudine Boban, a young girl whose head was turned with pathological vanity, obviously a monomaniac who must at all costs occupy the centre of the stage and be the cynosure of public attention, confessed that she had been to the Sabbat, and this was undoubtedly the case; but to walk or ride on horseback to the Sabbat were far too ordinary methods of locomotion, melodrama and the marvellous must find their place in her account and so she alleged: “that both she and her mother used to mount on a broom, and so making their exit by the chimney in this fashion they flew through the air to the Sabbat.”[6] Julian Cox (1664) said that one evening when she was in the fields about a mile away from the house “there came riding towards her three persons upon three Broom-staves, born up about a yard and a half from the ground.”[7] There is obvious exaggeration here; she saw two men and one woman bestriding brooms and leaping high in the air. They were, in fact, performing a magic rite, a figure of a dance. So it is recorded of the Arab crones that “In the time of the Munkidh the witches rode about naked on a stick between the graves of the cemetery of Shaizar.”[8] Nobody can refuse to believe that the witches bestrode sticks and poles and in their ritual capered to and fro in this manner, [6]a sufficiently grotesque, but by no means an impossible, action. And this bizarre ceremony, evidence of which—with no reference to flying through the air—is frequent, has been exaggerated and transformed into the popular superstition that sorcerers are carried aloft and so transported from place to place, a wonder they were all ready to exploit in proof of their magic powers. And yet it is not impossible that there should have been actual instances of levitation. For, outside the lives of the Saints, spiritistic séances afford us examples of this supernormal phenomenon, which, if human evidence is worth anything at all, are beyond all question proven.

As for the unguents wherewith the sorcerers anointed themselves we have the actual formulæ for this composition, and Professor A. J. Clark, who has examined these,[9] considers that it is possible a strong application of such liniments might produce unwonted excitement and even delirium. But long ago the great demonologists recognized and laid down that of themselves the unguents possessed no such properties as the witches supposed. “The ointment and lotion are just of no use at all to witches to aid their journey to the Sabbat,” is the well-considered opinion of Boguet who,[10] speaking with confident precision and finality, on this point is in entire agreement with the most sceptical of later rationalists.

The transformation of witches into animals and the extraordinary appearance at their orgies of “the Devil” under many a hideously unnatural shape, two points which have been repeatedly held up to scorn as self-evident impossibilities and proof conclusive of the untrustworthiness of the evidence and the incredibility of the whole system, can both be easily and fairly interpreted in a way which offers a complete and convincing explanation of these prodigies. The first metamorphosis, indeed, is mentioned and fully explained in the Liber Pœnitentialis[11] of S. Theodore, seventh Archbishop of Canterbury (668-690), capitulum xxvii, which code includes under the rubric De Idolatria et Sacrilegio “qui in Kalendas Ianuarii in ceruulo et in uitula uadit,” and prescribes: “If anyone at the Kalends of January goes about as a stag or a bull; that is, making himself into a wild animal and dressing in the skin of a herd animal, and putting on the [7]heads of beasts; those who in such wise transform themselves into the appearance of a wild animal, penance for three years because this is devilish.” These ritual masks, furs, and hides, were, of course, exactly those the witches at certain ceremonies were wont to don for their Sabbats. There is ample proof that “the Devil” of the Sabbat was very frequently a human being, the Grand Master of the district, and since his officers and immediate attendants were also termed “Devils” by the witches some confusion has on occasion ensued. In a few cases where sufficient details are given it is possible actually to identify “the Devil” by name. Thus, among a list of suspected persons in the reign of Elizabeth we have “Ould Birtles, the great devil, Roger Birtles and his wife, and Anne Birtles.”[12] The evil William, Lord Soulis, of Hermitage Castle, often known as “Red Cap,” was “the Devil” of a coven of sorcerers. Very seldom “the Devil” was a woman. In May, 1569, the Regent of Scotland was present at S. Andrews “quhair a notabill sorceres callit Nicniven was condemnit to the death and burnt.” Now Nicniven is the Queen of Elphin, the Mistress of the Sabbat, and this office had evidently been filled by this witch whose real name is not recorded. On 8 November, 1576, Elizabeth or Bessy Dunlop, of Lyne, in the Barony of Dalry, Ayrshire, was tried for sorcery, and she confessed that a certain mysterious Thom Reid had met her and demanded that she should renounce Christianity and her baptism, and apparently worship him. There can be little doubt that he was “the Devil” of a coven, for the original details, which are very full, all point to this. He seems to have played his part with some forethought and skill, since when the accused stated that she often saw him in the churchyard of Dalry, as also in the streets of Edinburgh, where he walked to and fro among other people and handled goods that were exposed on bulks for sale without attracting any special notice, and was thereupon asked why she did not address him, she replied that he had forbidden her to recognize him on any such occasion unless he made a sign or first actually accosted her. She was “convict and burnt.”[13] In the case of Alison Peirson, tried 28 May, 1588, “the Devil” was actually her kinsman, William Sympson, and she “wes conuict of the vsing of Sorcerie and Witchcraft, [8]with the Inuocatioun of the spreitis of the Deuill; speciallie in the visioune and forme of ane Mr. William Sympsoune, hir cousing and moder-brotheris-sone, quha sche affermit wes ane grit scoller and doctor of medicin.”[14] Conuicta et combusta is the terse record of the margin of the court-book.

One of the most interesting identifications of “the Devil” occurs in the course of the notorious trials of Dr. Fian and his associates in 1590-1. As is well known, the whole crew was in league with Francis Stewart, Earl of Bothwell, and even at the time well-founded gossip, and something more than gossip, freely connected his name with the spells, Sabbats, and orgies of the witches. He was vehemently suspected of the black art; he was an undoubted client of warlocks and poisoners; his restless ambition almost overtly aimed at the throne, and the witch covens were one and all frantically attempting the life of King James. There can be no sort of doubt that Bothwell was the moving force who energized and directed the very elaborate and numerous organization of demonolaters, which was almost accidentally brought to light, to be fiercely crushed by the draconian vengeance of a monarch justly frightened for his crown and his life.

In the nineteenth century both Albert Pike of Charleston and his successor Adriano Lemmi have been identified upon abundant authority as being Grand Masters of societies practising Satanism, and as performing the hierarchical functions of “the Devil” at the modern Sabbat.

God, so far as His ordinary presence and action in Nature are concerned, is hidden behind the veil of secondary causes, and when God’s ape, the Demon, can work so successfully and obtain not merely devoted adherents but fervent worshippers by human agency, there is plainly no need for him to manifest himself in person either to particular individuals or at the Sabbats, but none the less, that he can do so and has done so is certain, since such is the sense of the Church, and there are many striking cases in the records and trials which are to be explained in no other way.

That, as Burns Begg pointed out, the witches not unseldom “seem to have been undoubtedly the victims of unscrupulous and designing knaves, who personated Satan”[15] is no palliation of their crimes, and therefore they are not one [9]whit the less guilty of sorcery and devil-worship, for this was their hearts’ intention and desire. Nor do I think that the man who personated Satan at their assemblies was so much an unscrupulous and designing knave as himself a demonist, believing intensely in the reality of his own dark powers, wholly and horribly dedicated and doomed to the service of evil.

PLATE II

THE WORLD TOST AT TENNIS.

The First Quarto

[face p. 8

We have seen that the witches were upon occasion wont to array themselves in skins and ritual masks and there is complete evidence that the hierophant at the Sabbat, when a human being played that rôle, generally wore a corresponsive, if somewhat more elaborate, disguise. Nay more, as regards the British Isles at least—and it seems clear that in other countries the habit was very similar—we possess a pictorial representation of “the Devil” as he appeared to the witches. During the famous Fian trials Agnes Sampson confessed: “The deuell wes cled in ane blak goun with ane blak hat vpon his head.... His faice was terrible, his noise lyk the bek of ane egle, greet bournyng eyn; his handis and leggis wer herry, with clawes vpon his handis, and feit lyk the griffon.”[16] In the pamphlet Newes from Scotland, Declaring the Damnable life and death of Doctor Fian[17] we have a rough woodcut, repeated twice, which shows “the Devil” preaching from the North Berwick pulpit to the whole coven of witches, and allowing for the crudity of the draughtsman and a few unimportant differences of detail—the black gown and hat are not portrayed—the demon in the picture is exactly like the description Agnes Sampson gave. It must be remembered, too, that at the Sabbat she was obviously in a state of morbid excitation, in part due to deep cups of heady wine, the time was midnight, the place a haunted old church, the only light a few flickering candles that burned with a ghastly blue flame.

Now “the Devil” as he is shown in the Newes from Scotland illustration is precisely the Devil who appears upon the title-page of Middleton and Rowley’s Masque, The World tost at Tennis, 4to, 1620. This woodcut presents an episode towards the end of the masque, and here the Devil in traditional disguise, a grim black hairy shape with huge beaked nose, monstrous claws, and the cloven hoofs of a griffin, in every particular fits the details so closely observed by Agnes [10]Sampson. I have no doubt that the drawing for the masque was actually made in the theatre, for although this kind of costly and decorative entertainment was almost always designed for court or some great nobleman’s house we know that The World tost at Tennis was produced with considerable success on the public stage “By the Prince his Seruants.” The dress, then, of “the Devil” at the Sabbats seems frequently to have been an elaborate theatrical costume, such as might have been found in the stock wardrobe of a rich playhouse at London, but which would have had no such associations for provincial folk and even simpler rustics.

From time to time the sceptics have pointed to the many cases upon record of a victim’s sickness or death following the witch’s curse, and have incredulously inquired if it be possible that a malediction should have such consequences. Whilst candidly remarking that personally I believe there is power for evil and even for destruction in such a bane, that a deadly anathema launched with concentrated hate and all the energy of volition may bring unhappiness and fatality in its train, I would—since they will not allow this—answer their objections upon other lines. When some person who had in any way annoyed the witch was to be harmed or killed, it was obviously convenient, when practicable, to follow up the symbolism of the solemn imprecation, or it might be of the melted wax image riddled with pins, by a dose of subtly administered poison, which would bring about the desired result, whether sickness or death; and from the evidence concerning the witches’ victims, who so frequently pined owing to a wasting disease, it seems more than probable that lethal drugs were continually employed, for as Professor A. J. Clark records “the society of witches had a very creditable knowledge of the art of poisoning,”[18] and they are known to have freely used aconite, deadly nightshade (belladonna), and hemlock.

So far then from the confessions of the witches being mere hysteria and hallucination they are proved, even upon the most material interpretation, to be in the main hideous and horrible fact.

In choosing examples to demonstrate this I have as yet referred almost entirely to the witchcraft which raged from [11]the middle of the thirteenth to the beginning of the eighteenth century, inasmuch as that was the period when the diabolic cult reached its height, when it spread as a blight and a scourge throughout Europe and flaunted its most terrific proportions. But it must not for a moment be supposed, as has often been superficially believed, that Witchcraft was a product of the Middle Ages, and that only then did authority adopt measures of repression and legislate against the warlock and the sorceress. If attention has been concentrated upon that period it is because during those and the succeeding centuries Witchcraft blazed forth with unexampled virulence and ferocity, that it threatened the peace, nay in some degree, the salvation of mankind. But even pagan emperors had issued edicts absolutely forbidding goetic theurgy, confiscating grimoires (fatidici libri) and visiting necromancers with death. In A.U.C. 721 during the triumvirate of Octavius, Antony, and Lepidus, all astrologers and charmers were banished.[19] Maecenas called upon Augustus to punish sorcerers, and plainly stated that those who devote themselves to magic are despisers of the gods.[20] More than two thousand popular books of spells, both in Greek and Latin, were discovered in Rome and publicly burned.[21] In the reign of Tiberius a decree of the Senate exiled all traffickers in occult arts; Lucius Pituanius, a notorious wizard, they threw from the Tarpeian rock, and another, Publius Martius, was executed more prisco outside the Esquiline gate.[22]

Under Claudius the Senate reiterated the sentence of banishment: “De mathematicis Italia pellendis factum Senatus consultum, atrox et irritum,” says Tacitus.[23] During the few months he was emperor Vitellius proceeded with implacable severity against all soothsayers and diviners; many of whom, when accused, he ordered for instant execution, not even affording them the tritest formality of a trial.[24] Vespasian, again, his successor, refused to permit scryers and enchanters to set foot in Italy, strictly enforcing the existent statutes.[25] It is clear from all these stringent laws, and the list of examples might be greatly extended, that although under the Cæsars omens were respected, oracles were consulted, the augurs honoured, and haruspices revered, the dark influences and foul criminality of the [12]reverse of that dangerous science were recognized and its professors punished with the full force of repeated legislation.

M. de Cauzons has expressed himself somewhat vigorously when speaking of writers who trace the origins of Witchcraft to the Middle Ages: “C’est une mauvaise plaisanterie,” he remarks,[26] “ou une contrevérité flagrante, d’affirmer que la sorcellerie naquit au Moyen-Age, et d’attribuer son existence à l’influence ou aux croyances de l’Eglise.” (It is either a silly jest or inept irony to pretend that Witchcraft arose in the Middle Ages, to attribute its existence to the influence or the beliefs of the Catholic Church.)

An even more erroneous assertion is the charge which has been not infrequently but over-emphatically brought forward by partial ill-documented historians to the effect that the European crusade against witches, the stern and searching prosecutions with the ultimate penalty of death at the stake, are entirely due to the Bull Summis desiderantes affectibus, 5 December, 1484, of Pope Innocent VIII; or that at any rate this famous document, if it did not actually initiate the campaign, blew to blasts of flame and fury the smouldering and half-cold embers. This is most preposterously affirmed by Mackay, who does not hesitate to write[27]: “There happened at that time to be a pontiff at the head of the Church who had given much of his attention to the subject of Witchcraft, and who, with the intention of rooting out the supposed crime, did more to increase it than any other man that ever lived. John Baptist Cibo, elected to the papacy in 1485,[28] under the designation of Innocent VIII, was sincerely alarmed at the number of witches, and launched forth his terrible manifesto against them. In his celebrated bull of 1488, he called the nations of Europe to the rescue of the Church of Christ upon earth, ‘imperilled by the arts of Satan’” which last sentence seems to be a very fair statement of fact. Lecky notes the Bull of Innocent which, he extravagantly declares, “gave a fearful impetus to the persecution.”[29] Dr. Davidson, in a brief but slanderous account of this great pontiff, gives angry prominence to his severity “against sorcerers, magicians, and witches.”[30] It is useless to cite more of these superficial and crooked judgements; but since even authorities of weight and value have been deluded and fallen into the snare it is worth while [13]labouring the point a little and stressing the fact that the Bull of Innocent VIII was only one of a long series of Papal ordinances dealing with the suppression of a monstrous and almost universal evil.[31]

The first Papal Bull directly launched against the black art and its professors was that of Alexander IV, 13 December, 1258, addressed to the Franciscan inquisitors. And it is worth while here to examine precisely what was the earlier connotation of the terms “inquisitor” and “inquisition,” so often misunderstood, as our research, though brief, will throw a flood of light upon the subject of Witchcraft, and, moreover, incidentally will serve to explain how that those writers who assign the beginnings of Witchcraft to the Middle Ages, although most certainly and even demonstrably in error, have at any rate been very subtilely and easily led wrong, since sorcery in the Middle Ages was violently unmasked and the whole horrid craft then first authoritatively exposed in its darkest colours and most abominable manifestations, as had indeed existed from the first, but had been carefully hidden and scrupulously concealed.

By the term Inquisition (inquirere = to look into) is now generally understood a special ecclesiastical institution for combating or suppressing heresy, and the Inquisitors are the officials attached to the said institution, more particularly judges who are appointed to investigate the charges of heresy and to try the persons brought before them on those charges. During the first twelve centuries the Church was loath to deal with heretics save by argument and persuasion; obstinate and avowed heretics were, of course, excluded from her communion, a defection which in the ages of faith, naturally involved them in many and great difficulties. S. Augustine,[32] S. John Chrysostom,[33] S. Isidore of Seville[34] in the seventh century, and a number of other Doctors and Fathers held that for no cause whatsoever should the Church shed blood; but, on the other hand, the imperial successors of Constantine justly considered that they were obliged to have a care for the material welfare of the Church here on earth, and that heresy is always inevitably and inextricably entangled with attempts on the social order, always anarchical, always political. Even the pagan persecutor Diocletian recognized this fact, which heretics, until they obtain the [14]upper hand, have throughout the ages consistently denied and endeavoured to disguise. For in 287, less than two years after his accession, he sent to the stake the leaders of the Manichees; the majority of their followers were beheaded, and a few less culpable sent to perpetual forced labour in the government mines. Again in 296 he orders their extermination (stirpitus amputari) as a sordid, vile, and impure sect. So the Christian Cæsars, persuaded that the protection of orthodoxy was their sacred duty, began to issue edicts for the suppression of heretics as being traitors and anti-social revolutionaries.[35] But the Church protested, and when Priscillian, Bishop of Avila, being found guilty of heresy and sorcery,[36] was condemned to death by Maximus at Trier in 384, S. Martin of Tours addressed the Emperor in such plain terms that it was solemnly promised the sentence should not be carried into effect. However, the pledge was broken, and S. Martin’s indignation was such that for a long while he refused to hold communion with those who had been in any way responsible for the execution, which S. Ambrose roundly stigmatized as a heinous crime.[37] Even more crushing were the words of Pope S. Siricius, before whom Maximus was fain to humble himself in lowliest penitence, and the supreme pontiff actually excommunicated Bishop Felix of Trier for his part in the deed.

From time to time heretics were put to death under the civil law to which they were amenable, as in 556 when a band of Manichees were executed at Ravenna. Pope Pelagius I, who was consecrated that very year, when Paulinus of Fossombrone, rejecting his authority, openly stirred up schism and revolt, merely relegated the recalcitrant bishop to a monastery. Saint Cæsarius of Arles, who died in 547, speaking[38] of the punishment to be meted out to those who obstinately persevere in overt paganism, recommends that they should first be remonstrated with and reprimanded, that they should if possible be thus persuaded of their errors; but if they persist certain corporal chastisement is to be given; and in extreme cases a course of domestic discipline, the cutting of the hair close as a mark of indignity and confinement within doors under restraint, may be adopted. There is no hint of anything more than [15]private measures, no calling in of any ecclesiastical authority, far less an appeal to any punitive tribunal.

In the days of Charlemagne the aged Elipandus, Archbishop of Toledo, taught an offshoot of the Nestorian heresy, Adoptionism, a crafty but deadly error, to which he won the slippery dialectician Felix of Urgel. Felix, as a Frankish prelate, was summoned to Aix-la-Chapelle. A synod condemned his doctrine and he recanted, only to retract his words and to reiterate his blasphemies. He was again condemned, and again he recanted. But he proved shifty and tricksome to the last. For after his death Agobar of Lyons found amongst his papers a scroll asserting that of this heresy he was fully persuaded, in spite of any contradictions to which he might hypocritically subscribe. Yet Felix only suffered a short detention at Rome, whilst no measures seem to have been taken against Elipandus, who died in his errors. It was presumably considered that orthodoxy could be sufficiently served and vindicated by the zeal of such great names as Beatus, Abbot of Libana; Etherius, Bishop of Osma; S. Benedict of Aniane; and the glorious Alcuin.[39]

Some forty years later, about the middle of the ninth century, Gothescalch, a monk of Fulda, caused great scandal by obstinately and impudently maintaining that Christ had not died for all mankind, a foretaste of the Calvinistic heresy. He was condemned at the Synods of Mainz in 848, and of Kiersey-sur-Oise in 849, being sentenced to flogging and imprisonment, punishments then common in monasteries for various infractions of the rule. In this case, as particularly flagrant, it was Hinemar, Archbishop of Rheims, a prelate notorious for his severity, who sentenced the culprit to incarceration. But Gothescalch had by his pernicious doctrines been the cause of serious disturbances; and his inflammatory harangues had excited tumults, sedition, and unrest, bringing odium upon the sacred habit. The sentence of the Kiersey Synod ran: “Frater Goteschale ... quia et ecclesiastica et ciuilia negotia contra propositum et nomen monachi conturbare iura ecclesiastica præsumpsisti, durissimis uerberibus te cagistari et secundum ecclesiasticas regulas ergastulo retrudi, auctoritate episcopali decernimus.” (Brother Gothescalch, ... because thou hast dared—contrary [16]to thy monastic calling and vows—to concern thyself in worldly as well as spiritual businesses and hast violated all ecclesiastical law and order, by our episcopal authority we condemn thee to be severely scourged and according to the provision of the Church to be closely imprisoned.)

From these instances it will be seen that the Church throughout all those centuries of violence, rapine, invasion, and war, when often primitive savagery reigned supreme and the most hideous cruelty was the general order of the day, dealt very gently with the rebel and the heretic, whom she might have executed wholesale with the greatest ease; no voice would have been raised in protest save that of her own pontiffs, doctors, and Saints; nay, rather, such repression would have been universally applauded as eminently proper and just. But it was the civil power who arraigned the anarch and the misbeliever, who sentenced him to death.

About the year 1000, however, the venom of Manichæism obtained a new footing in the West, where it had died out early in the sixth century. Between 1030-40 an important Manichæan community was discovered at the Castle of Monteforte, near Asti, in Piedmont. Some of the members were arrested by the Bishop of Asti and a number of noblemen in the neighbourhood, and upon their refusal to retract the civil arm burned them. Others, by order of the Archbishop of Milan, Ariberto, were brought to that city since he hoped to convert them. They answered his efforts by attempts to make proselytes; whereupon Lanzano, a prominent noble and leader of the popular party, caused the magistrates to intervene and when they had been taken into the custody of the State they were executed without further respite. For the next two hundred years Manichæism spread its infernal teaching in secret until, towards the year 1200, the plague had infected all Italy and Southern Europe, had reached northwards to Germany, where it was completely organized, and was not unknown in England, since as early as 1159 thirty foreign Manichees had privily settled here. They were discovered in 1166, and handed over to the secular authorities by the Bishops of the Council of Oxford. In high wrath Henry II ordered them to be scourged, branded in the forehead, and cast adrift in the cold [17]of winter, straightly forbidding any to succour such vile criminals, so all perished from cold and exposure. Manichæism furthermore split up into an almost infinite number of sects and systems, prominent amongst which were the Cathari, the Aldonistæ and Speronistæ, the Concorrezenses of Lombardy, the Bagnolenses, the Albigenses, Pauliciani, Patarini, Bogomiles, the Waldenses, Tartarins, Beghards, Pauvres de Lyon.

It must be clearly borne in mind that these heretical bodies with their endless ramifications were not merely exponents of erroneous religious and intellectual beliefs by which they morally corrupted all who came under their influence, but they were the avowed enemies of law and order, red-hot anarchists who would stop at nothing to gain their ends. Terrorism and secret murder were their most frequent weapons. In 1199 the Patarini followers of Ermanno of Parma and Gottardo of Marsi, two firebrands of revolt, foully assassinated S. Peter Parenzo, the governor of Orvieto. On 6 April, 1252, whilst returning from Como to Milan, as he passed through a lonely wood S. Peter of Verona was struck down by the axe of a certain Carino, a Manichæan bravo, who had been hired to the deed.[40] By such acts they sought to intimidate whole districts, and to compel men’s allegiance with blood and violence. The Manichæan system was in truth a simultaneous attack upon the Church and the State, a desperate but well-planned organization to destroy the whole fabric of society, to reduce civilization to chaos. In the first instance, as the Popes began to perceive the momentousness of the struggle they engaged the bishops to stem the tide. At the Council of Tours, 1163, Alexander III called upon the bishops of Gascony to take active measures for the suppression of these revolutionaries, but at the Lateran Council of 1179 it was found these disturbers of public order had sown such sedition in Languedoc that an appeal was made to the secular power to check the evil. In 1184 Lucius III issued from Verona his Bull Ad Abolendam which expressly mentions many of the heretics by name, Cathari, Patarini, Humiliati, Pauvres de Lyon, Pasagians, Josephins, Aldonistæ. The situation had fast developed and become serious. Heretics were to be sought out and suitably punished, by which, however, capital punishment is not [18]intended. Innocent III, although adding nothing essential to these regulations yet gave them fuller scope and clearer definition. In his Decretals he precisely speaks of accusation, denunciation, and inquisition, and it is obvious that these measures were necessary in the face of a great secret society aiming at nothing less than the destruction of the established order, for all the sectaries were engaged upon the most zealous propaganda, and their adherents had spread like a network over the greater part of Europe. The members bore the title of “brother” and “sister,” and had words and signs by which the initiate could recognize one another without betraying themselves to others.[41] Ivan de Narbonne, who was converted from this heresy, in a letter to Giraldus, Archbishop of Bordeaux, as quoted by Matthew of Paris, says that in every city where he travelled he was always able to make himself known by signs.[42]

It was necessary that the diocesan bishops should be assisted in their heavy task of tracking down heretics, and accordingly the Holy See had resource to legates who were furnished with extraordinary powers to cope with so perplexing a situation. In 1177 as legate of Alexander III, Peter, Cardinal of San Crisogono, at the particular request of Count Raymond V, visited the Toulouse district to check the rising tide of Catharist doctrine.[43] In 1181, Henry, Abbot of Clairvaux, who had been in his suite, now Cardinal of Albano, as legate of the same Pope, received the submission of various heretical leaders, and, so extensive were his powers, solemnly deposed the Archbishops of Lyons and Narbonne. In 1203 Peter of Castelnau and Raoul were acting at Toulouse on behalf of Innocent III, seemingly with plenipotentiary authority. The next year Arnauld Amaury, Abbot of Citeaux, was joined to them to form a triple tribunal with absolute power to judge heretics in the provinces of Aix, Arles, Narbonne, and the adjoining dioceses. At the death of Innocent III (1216) there existed an organization to search out heretics; episcopal tribunals at which often sat an assessor (the future inquisitor) to watch the conduct of the case; and above all the legate to whom he might make a report. The legate, from his position, was naturally a prelate occupied with a vast number of urgent affairs—Arnauld Amaury, for example, was absent for a considerable [19]time to take part in the General Chapter at Cluny—and gradually more and more authority was delegated to the assessor, who insensibly developed into the Inquisitor, a special but permanent judge acting in the name of the Pope, by whom he was invested with the right and the duty to deal legally with offences against the Faith. And as just at this time there came into being two new Orders, the Dominicans and Franciscans, whose members by their theological training and the very nature of their vows seemed eminently fitted to perform the inquisitorial task with complete success, absolutely uninfluenced by any worldly motive, it is natural that the new officials should have been selected from these Orders, and, owing to the importance attached by the Dominicans to the study of divinity, especially from their learned ranks.

It is very obvious why the Holy See so sagaciously preferred to assign the prosecution of heretics, a matter of the first importance, to an extraordinary tribunal rather than leave the trials in the hands of the bishops. Without taking into consideration the fact that these new duties would have seriously encroached upon, if not wholly absorbed, the time and activities of a bishop, the prelates who ruled most dioceses were the subject of some monarch with whom they might have come in conflict on many a delicate point which could easily be conceived to arise, and the result of such disagreement would have been fraught with endless political difficulties and internal embarrassments. A court of religious, responsible to the Pope alone, would act more fairly, more freely, without fear or favour. The profligate Philip I of France, for example, during his long, worthless, and dishonoured reign (1060-1108), by his evil courses drew upon himself the censure of the Church, whereupon he banished the Bishop of Beauvais and revoked the decisions of the episcopal courts.[44] In a letter[45] to William, Count of Poitiers, Pope S. Gregory VII energetically declares that if the King does not cease from molesting the bishops and interfering with their judicature a sentence of excommunication will be launched. In another letter the same pontiff complains of the disrespect shown to the ecclesiastical tribunals, and addressing the French bishops he cries: “Your king, who sooth to say should be termed not a king [20]but a cruel tyrant, inspired by Satan, is the head and cause of these evils. For he has notoriously passed all his days in foulest crimes, in seeking to do wickedness and to ensue it.”[46] The conflict of the bishops of a realm with an unworthy and evil monarch is a commonplace of history. These troubles could scarcely arise in the case of courts forane.

The words “inquisition” and “inquisitors” began definitely to acquire their accepted signification in the earlier half of the thirteenth century. Thus in 1235 Gregory IX writes to the Archbishop of Sens: “Know then that we have charged the Provincial of the Order of Preachers in this same realm to nominate certain of his brethren, who are best fitted for so weighty a business, as Inquisitors that they may proceed against all notorious evildoers in the aforesaid realm ... and we also charge thee, dear Brother, that thou shouldest be instant and zealous in this matter of establishing an Inquisition by the appointment of those who seem to be best fitted for such a work, and let thy loins be girded, Brother, to fight boldly the battles of the Lord.”[47] In 1246 Innocent IV wrote to the Superiors of the Franciscans giving them leave to recall at will: “those brethren who have been sent abroad to preach the Mystery of the Cross of Christ, or to seek out and take measure against the plague sore of heresy.”[48]

All the heresies, and the Secret Societies of heretics, which infested Europe during the Middle Ages were Gnostic, and even more narrowly, Manichæan in character. The Gnostics arose almost with the advent of Christianity as a School or Schools who explained the teachings of Christ by blending them with the doctrines of pagan fantasts, and thus they claimed to have a Higher and a Wider Knowledge, the Γνῶσις the first exponent of which was unquestionably Simon Magus. “Two problems borrowed from heathen philosophy,” says Mansel,[49] “were intruded by Gnosticism on the Christian revelation, the problem of absolute existence, and the problem of the Origin of Evil.” The Gnostics denied the existence of Free-will, and therefore Evil was not the result of Man’s voluntary transgression, but must in some way have emanated from the Creator Himself. Arguing on these lines the majority asserted that the Creator must have been a malignant power, Lord of the Kingdom of Darkness, [21]opposed to the Supreme and Ineffable God. This doctrine was taught by the Gnostic sects of Persia, which became deeply imbued with the religion of Zoroaster, who assumed the existence of two original and independent Powers of Good and of Evil. Each of these Powers is of equal strength, and supreme in his own dominions, whilst constant war is waged between the two. This doctrine was particularly held by the Syrian Gnostics, the Ophites, the Naasseni, the Peratæ, the Sethians, amongst whom the serpent was the principal symbol. As the Creator of the world was evil, the Tempter, the Serpent, was the benefactor of man. In fact, in some creeds he was identified with the Logos. The Cainites carried out the Ophite doctrines to their fullest logical conclusion. Since the Creator, the God of the Old Testament, is evil all that is commended by the Scripture must be evil, and conversely all that is condemned therein is good. Cain, Korah, the rebels, are to be imitated and admired. The one true Apostle was Judas Iscariot. This cult is very plainly marked in the Middle Ages among the Luciferians; and Cainite ceremonies have their place in the witches’ Sabbat.[50]

All this Gnostic teaching was summed up in the gospel of the Persian Mani, who, when but a young man of twenty-six, seems first to have proclaimed in the streets and bazaars of Seleucia-Ctesiphon his supposed message on Sunday, 20 March, 242, the coronation festival of Shapur I. He did not meet with immediate success in his own country, but here and there his ideas took deep root. In 276-277, however, he was seized and crucified by the grandson of Shapur, Bahram I, his disciples being relentlessly pursued. Whenever Manichees were discovered they were brought to swift justice, executed, held up to universal hatred and contempt. They were considered by Moslems as not merely Unbelievers, the followers of a false impostor, but unnatural and unsocial, a menace to the State. It was for no light cause that the Manichee was loathed and abhorred both by faithful Christian and by those who proclaimed Mohammed as the true prophet of Allah. But later Manichæism spread in every direction to an extraordinary degree, which may perhaps be accounted for by the fact that it is in some sense a synthesis of the Gnostic philosophies, the theory of two eternal principles, good and evil, being especially emphasized. [22]Moreover, the historical Jesus, “the Jewish Messias, whom the Jews crucified,” was “a devil, who was justly punished for interfering in the work of the Æon Jesus,” who was neither born nor suffered death. As time went on, the elaborate cosmogony of Mani disappeared, but the idea that the Christ must be repudiated remained. And logically, then, worship is due to the enemy of Christ, and a sub-sect, the Messalians or Euchites, taught that divine honours must be paid to Satan, who is further to be propitiated by means of every possible outrage done to Christ. This, of course, is plain and simple Satanism openly avowed. Carpocrates even went so far as to aggravate the teaching of the Cainites, for he made the performance of every species of sin forbidden in the Old Testament a solemn duty, since this was the completest mode of showing defiance to the Evil Creator and Ruler of the World. This doctrine was wholly that of mediæval witches, and is flaunted by modern Satanists. Although the Manichees affected the greatest purity, it is quite certain that not unchastity but the act of generation alone was opposed to their views; secretly they practised the most hideous obscenities.[51] The Messalians in particular, vaunted a treatise Asceticus, which was condemned by the Third General Council of Ephesus (431) as “that filthy book of this heresy,” and in Armenia, in the fifth century, special edicts were passed to restrain their immoralities, so that their very name became the equivalent for “lewdness.” The Messalians survived unto the Middle Ages as Bogomiles.

Attention has already been drawn to the striking fact that even Diocletian legislated with no small vigour against the Manichees, and when we find Valentinian I and his son Gratian, although tolerant of other bodies, passing laws of equal severity in this regard (372), we feel that such interdiction is especially significant. Theodosius I, by a statute of 381, declared Manichees to be without civil rights, and incapable of inheriting; in the following year he condemned them to death, and in 389 he sternly directed the rigorous enforcement to the letter of these penalties.

Valentinian II confiscated their goods, annulled their wills, and sent them into exile. Honorius in 399 renewed the draconian measures of his predecessors; in 405 he heavily fined all governors of provinces or civil magistrates who were [23]slack in carrying out his orders; in 407 he pronounced the sect outlaws and public criminals having no legal status whatsoever, and in 408 he reiterated the former enactments in meticulous detail to afford no loophole of escape. Theodosius II (423), again, repeated this legislation, whilst Valentinian III passed fresh laws in 425 and 445. Anastasius once more decreed the penalty of death, which was even extended by Justin and Justinian to convert from Manichæism who did not at once denounce their former coreligionists to the authorities. This catena of laws which aims at nothing less than extermination is of singular moment.

About 660 arose the Paulicians, a Manichæan sect, who rejected the Old Testament, the Sacraments, and the Priesthood. In 835 it was realized that the government of this body was political and aimed at revolution and red anarchy. In 970 John Zimisces fixed their headquarters in Thrace. In 1115 Alexis Comnenus established himself during the winter at Philippopolis, and avowed his intention of converting them, the only result being that the heretics were driven westward and spread rapidly in France and Italy.

The Bogomiles were also Manichees. They openly worshipped Satan, repudiating Holy Mass and the Passion, rejecting Holy Baptism for some foul ceremony of their own, and possessing a peculiar version of the Gospel of S. John. As Cathari these wretches had their Centre for France at Toulouse; for Germany at Cologne; whilst in Italy, Milan, Florence, Orvieto, and Viterbo were their rallying-points. Their meetings were often held in the open air, on mountains, or in the depths of some lone valley; the ritual was very secret, but we know that at night they celebrated their Eucharist of Consolamentum, when all stood in a circle round a table covered with a white cloth and numerous torches were kindled, the service being closed by the reading of the first seventeen verses of their transfigured gospel. Bread was broken, but there is a tradition that the words of consecration were not pronounced according to the Christian formula; in some instances they were altogether omitted.

During the eleventh century, then, there began to spread throughout Europe a number of mysterious organizations whose adherents, in a secrecy that was all but absolute, practiced obscure rites embodying their beliefs, the central [24]feature of which was the adoration of the evil principle, the demon. But what is this save Satanism, or in other words Witchcraft? It is true that when these heresies came into sharp conflict with the Catholic Church they developed on lines which lost various non-essential accretions and Eastern subtleties of extravagant thought, but the motive of the Manichæan doctrines and of Witchcraft is one and the same, and the punishment of Manichees and of witches was the same death at the stake. The fact that these heretics were recognized as sorcerers will explain, as nothing else can, the severity of the statutes against them, evidence of no ordinary depravity, and early in the eleventh century Manichee and warlock are recognized as synonymous.