Title: German composition

A theoretical and practical guide to the art of translating English prose into German

Author: Hermann Lange

Release date: September 12, 2025 [eBook #76864]

Language: English

Original publication: Oxford: At the Clarendon Press, 1900

Credits: Jens Sadowski, MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: German words and phrases in the original were set in Fraktur, also known as Gothic or blackletter typeface. This HTML version will use the following fonts to approximate this, if you have them installed:

If you prefer not to or are unable to install one of these fonts, the German words will display in cursive instead.

[i]

Clarendon Press Series

LANGE’S GERMAN COURSE

COMPOSITION

[ii]

HENRY FROWDE, M.A.

PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

LONDON, EDINBURGH, AND NEW YORK

[iii]

Clarendon Press Series

GERMAN COMPOSITION

A THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL GUIDE

TO THE ART OF TRANSLATING ENGLISH PROSE

INTO GERMAN

BY

HERMANN LANGE

LECTURER ON FRENCH AND GERMAN AT THE MANCHESTER TECHNICAL SCHOOL

AND LECTURER ON GERMAN AT THE MANCHESTER ATHENÆUM

THIRD EDITION

With the German Spelling revised to meet the requirements of the

Government Regulations of 1880

Oxford

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

M DCCCC

[iv]

Oxford

PRINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

BY HORACE HART, M.A.

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

[v]

‘German Composition’ is intended to be a Theoretical and Practical Guide to the Art of Translating English Prose into good and idiomatic German. It is arranged in such a manner that students who have reached the fiftieth Lesson of the ‘German Manual’ may commence and advantageously use it conjointly with that book. Being complete in itself, it is likewise adapted for the use of any other students who, possessing a knowledge of German Accidence and having had some practice in reading German Prose, wish to acquire the Art of Translating English Prose into German.

The book is calculated to serve the requirements of the B.A. Examinations of the London and Victoria Universities, the Competitive Examinations for the Civil and Military Service, the Oxford and Cambridge Local Examinations for Senior Students, the Examination of the College of Preceptors for First Class Candidates, and of similar Public Examinations—all of which require the candidates to translate English Prose into German.

I may conscientiously say that I have done all I could to make the book attractive and useful. The selection of the Extracts has been made with the greatest care directly from the works of the various authors, and is the result of many years’ attentive reading and research. The pieces have been almost exclusively chosen from the works of the best modern English and American writers, and, it is hoped, will be found as interesting and instructive as they are well adapted for translation into German. They represent all the various styles of English Prose Composition, and contain a great variety of subjects, as a glance at the various pages will show; whilst the fact that the specimens, with only one or two exceptions, are no mere fragments, but complete pieces in themselves, must necessarily add to their value.

The Biographical Sketches of famous men and women, which at intervals appear in the Notes and are always given in German, form a special feature of the book. (Comp. S. 127, N. 1; S. 138, N. 12; and [vi]S. 156, N. 1.) They are of various lengths, according to their importance, and have been written to add to the interest of the work and at the same time to offer the student some useful material for reading German.

With respect to the help given in the Notes, I may state that I have proceeded with the utmost consideration and care. The great object I placed before me was to show, by precept and example, that a good translation cannot be produced by the mere mechanical process of joining together a number of words, as the dictionary may offer them at first sight: but that it requires great thought and analytic power; that every sentence, nay, almost every word, has to be weighed and considered with respect to its true bearing upon the text; and that a good rendering is only possible when the translator has grasped the true meaning of the passage before him.

I have endeavoured to give neither too little nor too much help, but whenever I found a difficulty which a student of average ability could not fairly be expected to overcome, I have stepped in to solve it. For this purpose I have made use of English equivalents and periphrases and of Rules and Examples, and in cases where neither of these helps was considered practicable I have not hesitated to give the German rendering of the word or passage to be translated. The last mode of procedure, however, I have adopted only when I found that the dictionaries in ordinary use were insufficient, as is so frequently the case, and more especially with respect to idiomatic passages, which it is impossible to render successfully unless the translator is well versed in both languages, and at the same time has undergone a thorough training in the Art of Translating English into German, which the present volume professes to teach. The plan of indicating the rendering of words and phrases by means of English equivalents and periphrases must be of evident advantage to the learner, for it teaches him how to think and analyse, whilst it leads him to render the word or phrase correctly without giving him the translation itself.

The Notes of Sections 1 to 150 and the Appendix contain in a concise and lucid form almost all the rules relating to the German Syntax, and in most instances these rules have been illustrated by practical examples and models. The Appendix gives in thirty-seven paragraphs the Rules referring to the Construction, the use of the Indicative, Subjunctive (or Conjunctive), and Conditional Moods, which for convenient reference have been reprinted from my ‘German Grammar,’ and to facilitate the student’s work I have added an Index to the Grammatical Rules and Idiomatic Renderings.

[vii]

In a work containing such a great number of Extracts as the present, there are, of course, many idioms and passages which may be correctly translated in various ways, and I can therefore scarcely hope that all my renderings will meet with the approval of every German scholar. I may, however, confidently affirm here that I have devoted much thought and labour to this publication, and that I have tried with all my heart to make it acceptable to teachers and students alike.

In conclusion I respectfully tender my best thanks to the publishers—

| Messrs. W. and R. Chambers, | Edinburgh, | |

| ” Chapman and Hall, | } | London, |

| ” Longmans and Co., | } | |

| ” Sampson Low and Co., | } | |

| ” Macmillan and Co., | } | |

| Mr. Murray, | } | |

| Messrs. T. Nelson and Sons, | } | |

| ” Smith, Elder, and Co., and | } | |

| ” Stanford and Co., | } |

and to the Editors of—

| The Daily News, | } | London, |

| ” Daily Telegraph, | } | |

| ” Globe, | } | |

| ” Standard, and | } | |

| ” Times, | } |

for their very kind permission to make use of the Copyright Extracts in this publication, and for the cordial manner in which they granted my request.

Page ix contains a few Hints and Directions for using the Book which I consider of great importance, and to which I beg to draw attention.

HERMANN LANGE.

Heathfield House, Lloyd Street,

Greenheys, Manchester,

September, 1883.

[viii]

A second edition of this volume having been called for, I wish to express my cordial thanks to the numerous colleagues and friends who adopted it as a text-book for their classes.

As I am engaged in preparing, besides this book, a third edition of two other volumes of my ‘German Course,’ and, at the request of the Delegates of the University Press, also a Key to this volume, ‘German Composition,’ I think the present moment opportune for introducing the reformed German spelling which, by Government regulations, has been taught in German schools for the last five or six years, and is becoming more generally used from year to year in friendly intercourse, papers, periodicals, literature, and commercial correspondence. It is but fair that the students of German in this country should be taught to spell in the simplified way now universally practised by their German contemporaries. They will at least have nothing to unlearn then; and, although the present spelling-reform may be considered but a compromise between the older and the younger schools, there being a tendency in the younger men to go even further than their older colleagues in the simplification of our orthography and to make it still more phonetic and uniform in principle, it will take a long time before the Government will be moved to make modifications of any importance in their regulations. I confidently trust that the great trouble I have bestowed upon the revision of the present edition will be appreciated by teachers and students alike. It will easily be seen that the alterations of the orthography in the various books forming this ‘German Course’ must have necessarily entailed a very considerable additional expense; but the publication having met with much approval on the part of the public, I was anxious to leave nothing undone in order to adapt it in every respect to the requirements of the times and to make it still more useful.

On examination it will be seen that the changes made are not so many as may be supposed, and that the principles underlying the German spelling-reform are simple and easy to understand.

At the end of the Appendix will be found a Synopsis of the principal changes the German spelling has undergone, accompanied by Examples and a few Exceptions to the general rules.

HERMANN LANGE.

Heathfield House, Lloyd Street, Greenheys, Manchester,

December, 1886.

[ix]

Each Section should first be prepared for viva voce translation, with the assistance of the Notes in class; then translated in writing; carefully corrected; and finally practised, by comparing the English text with the corrected German version, for a second viva voce translation until the student is able to translate the English text, without the assistance of the Notes in class, just as readily into correct German as if he were reading from a German book.

The Grammatical Rules given in the Notes should always be carefully studied, and the reading of previously given Rules and the various paragraphs of the Appendix referred to in the text should never be omitted.

The strict and conscientious observance of these directions is earnestly requested.

The second viva voce translation without the assistance of the Notes in class, as explained above, is especially of the greatest importance to the student’s progress in the Art of Translating English into German, and is the only way of mastering all the idiomatic and syntactic difficulties contained in the Lessons and explained in the foot-notes. It commends itself likewise as the best way of committing to memory the great number of words and the various forms of construction occurring in the text, and will gradually, but surely, lead to the acquisition of a good and thorough German style of writing.

To be quite clear the Author ventures to propose the following

Prepare for viva voce translation Sections 1 and 2, with the assistance of the Notes in class.

Translate in Writing Sections 1 and 2; and prepare for viva voce translation Sections 3 and 4, with the assistance of the Notes in class.

Prepare for fluent and correct viva voce translation Sections 1 and 2, without the assistance of the Notes in class, by comparing the English [x]text with the corrected German version; translate in Writing Sections 3 and 4; and prepare for viva voce translations Sections 5 and 6, with the assistance of the Notes in class.

Prepare for fluent and correct viva voce translation Sections 3 and 4, without the assistance of the Notes in class, by comparing the English text with the corrected version; translate in Writing Sections 5 and 6; and prepare for viva voce translation Sections 7 and 8, with the assistance of the Notes in class;

Then proceed in the same way throughout the book.

It need scarcely be added that the quantity of work pointed out here may be diminished or increased according to circumstances, and that the longer sections towards the end of the book will in most cases require the former course.

The frequent attentive study of German literature will be a powerful auxiliary to this book in imparting the Art of Translating English Prose into German.

[xi]

| Acc. | Accusative. |

| adj. | adjective. |

| adv. | adverb. |

| App. | Appendix |

| art. | article. |

| Comp. | compare. |

| comp. | compound. |

| conj. | conjunction |

| constr. | construction. |

| contr. | contracted. |

| Dat. (or dat.) | Dative. |

| def. | definite. |

| d. h. | (das heißt), that is. |

| demonstr. | demonstrative. |

| e.g. | (exempli gratia) for example. |

| etc. | (et cetera), and so forth. |

| Expl. | Example. |

| fem., or (f.) | feminine. |

| geb. | (geboren), born. |

| Gen. | Genitive. |

| i.e. | (id est), that is. |

| Impf. | Imperfect. |

| impers. | impersonal. |

| indef. | indefinite. |

| Inf. | Infinitive. |

| insep. | inseparable. |

| intr., or intrans. | intransitive. |

| Liter. | Literally. |

| m., or (m.) | masculine. |

| N. | Note |

| n. | noun. |

| neut., or (n.) | neuter. |

| Nom. | Nominative. |

| p. p. | Past Participle. |

| p. ps. | Past Participles. |

| pers. | person. |

| persnl. | personal. |

| posses. | possessive. |

| prep. | preposition. |

| Pres. | Present. |

| pres. p. | Present Participle. |

| pron. | pronoun. |

| refl. | reflective. |

| reg. | regular. |

| relat. | relative. |

| S. | Section. |

| Sing. | Singular. |

| str. | strong. |

| Subj. | Subjunctive. |

| tr., or trans. | transitive. |

| u. a. | (und andere), and others. |

| u. s. w. | (und so weiter), and so forth. |

| v. | verb. |

| viz. | (videlicet), namely, to wit. |

| w. | weak. |

| § | paragraph. |

| † | (gestorben), died. |

| = | is equivalent to. |

[xii]

[xiii]

| PAGE | ||

| Preface | v | |

| Directions for Using the Book | ix | |

| Abbreviations and Signs Explained | xi | |

| SECT. | ||

| 1. | A Good Maxim.—Sir Thomas Buxton | 1 |

| 2. | What is Eternity?—Rev. R. K. Arvine | 1 |

| 3. | The Action of Water.—Dr. Lankester | 2 |

| 4. | Of what Use is it?—S. Smiles | 2 |

| 5. | Wealth.—Rev C. Cotton | 3 |

| 6. | Mendelssohn in Birmingham.—Athenæum | 3 |

| 7. | To Forgive is to Forget.—Rev. H. W. Beecher | 3 |

| 8. | What is Capital?—Rev. Dr. Macduff | 4 |

| 9. | A Good Rule.—S. Smiles | 4 |

| 10. | England under the Rule of Queen Victoria.—W. M. Thackeray | 5 |

| 11. | Concentration of Powers.—T. Carlyle | 5 |

| 12. | Coolness.—W. C. Hazlitt | 6 |

| 13. | Religious Toleration.—Rev R. K. Arvine | 6 |

| 14. | How Hugh Miller became a Geologist.—S. Smiles | 7 |

| 15. | Extremes Meet.—Rev. R. K. Arvine | 7 |

| 16. | Poor Pay.—Rev. R. K. Arvine | 8 |

| 17. | The World is a Looking-glass.—W. M. Thackeray | 8 |

| 18. | Give the honour to God alone.—Rev. R. K. Arvine | 9 |

| 19. | How did Cuvier become a Naturalist?—S. Smiles | 9 |

| 20. | On the Choice of Books.—Lord Dudley | 10 |

| 21. | An apparently insignificant fact often leads to great results.—S. Smiles | 10 |

| 22. | Oats.—Nelson’s Readers | 11 |

| 23. | Spring Blossoms.—Rev. E. M. Davies | 11 |

| 24. | The Winking Eyelid.—Prof. G. Wilson | 11 |

| 25. | A Good Example.—Rev. J. Burroughs | 12 |

| 26. | Description of a Glacier.—Mrs. Beecher Stowe | 12 |

| 27. | Without Pains no Gains.—S. Smiles | 13 |

| 28. | The Magna Charta.—Lord Macaulay | 14 |

| 29. | Honesty.—Dr. B. Franklin | 14 |

| 30, 31. | Formation of a Coral-Island.—M. Flinders | 15, 16 |

| 32. | Reynard Caught.—Anonymous | 16 |

| 33, 34. | The Means of Conveyance in the Time of Charles II.—Lord Macaulay | 17 |

| 35. | Sir William Herschel.—Rev. Dr. Leitch | 18[xiv] |

| 36, 37. | The Air-Ocean.—Maury | 19, 20 |

| 38. | Cheerful Church-Music.—Rev. R. K. Arvine | 20 |

| 39. | Our Industrial Independence depends upon Ourselves.—S. Smiles | 21 |

| 40. | England’s Trees.—Hewitt | 21 |

| 41-45. | The Indian Chief.—Washington Irving | 22-24 |

| 46. | Rice.—Nelson’s Readers | 25 |

| 47-53. | The White Ship.—Charles Dickens | 26-30 |

| 54. | Barley.—Nelson’s Readers | 30 |

| 55. | The soldier and his Flag.—General Bourrienne | 31 |

| 56. | Our cultivated Native Plants.—Hewitt | 32 |

| 57, 58. | The Bequest.—Anonymous | 32, 33 |

| 59. | Wheat.—Nelson’ Readers | 33 |

| 60. | Occupation of the Anglo-Saxons.—Milner | 34 |

| 61-68. | Tender, Trusty, and True.—Rev. Robert Collyer | 34-39 |

| 69. | Despatch of Business.—Sir Walter Scott | 39 |

| 70, 71. | On Perfumery.—Prof. Ascher | 40, 41 |

| 72. | On Instinct.—Rev. S. Smith | 41 |

| 73. | Peter the Great and the Monk.—Anonymous | 42 |

| 74, 75. | The Beauty of the Eye.—Prof. G. Wilson | 43 |

| 76. | A Funeral Dance.—Sir S. Baker | 44 |

| 77. | Absolution Beforehand.—Rev. R. K. Arvine | 45 |

| 78, 79. | Stand up for whatever is True, Manly, and Lovely.—T. Hughes | 46, 47 |

| 80. | Work is a great Comforter.—Anonymous | 47 |

| 81. | Perseverance finds its Reward.—N. Goodrich | 48 |

| 82. | The Necessity of Volcanoes.—Rev. Prof. Hitchcock | 49 |

| 83. | The Power of Beauty.—Lord Shaftesbury | 49 |

| 84. | The English Climate.—Hewitt | 50 |

| 85, 86. | The London Docks.—The “Globe” Newspaper | 50, 51 |

| 87. | Dr. Johnson on Debt.—S. Smiles | 52 |

| 88-94. | A Curious Instrument.—Jane Taylor | 53-57 |

| 95. | Anglo-Saxon Dress.—Milner | 57 |

| 96, 97. | The Glaciers at Sunset.—Mrs. Beecher Stowe | 58, 59 |

| 98, 99. | The Lost Child Found.—Jacob Abbott | 59, 60 |

| 100. | Perspiration.—Rev Dr. Dick | 61 |

| 101-107. | The Drama of the French Revolution of 1848.—Essays from “The Times” | 61-69 |

| 108. | Experience is the best Teacher.—W. C. Hazlitt | 69 |

| 109. | On Self Culture.—William Chambers | 70 |

| 110, 111. | Goethe’s Death.—G. H. Lewes | 70, 71 |

| 112. | On Travelling.—Charles Kingsley | 72 |

| 113. | The Management of the Body.—Sidney Smith | 73 |

| 114. | The Sources of Water.—Dr. Lankester | 73 |

| 115. | The Art of Oratory.—Henry Clay | 74 |

| 116. | Early Privations.—S. Smiles | 75[xv] |

| 117, 118. | The Blessedness of Friendship.—Charles Kingsley | 76 |

| 119, 120. | Do Good in your own Sphere of Action.—Thos. Hughes | 77, 78 |

| 121, 122. | The State of Ireland.—The Right Hon. John Bright | 79 |

| 123-125. | On Ragged Schools.—Dr. Guthrie | 80-82 |

| 126. | Shylock Meditating Revenge.—Shakespeare | 82 |

| 127, 128. | Character of Charlemagne.—Hallam | 83, 84 |

| 129-131. | Goethe’s Daily Life at Weimar.—G. H. Lewes | 85-87 |

| 132. | The Progress in the Art of Printing.—The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone | 88 |

| 133. | Robert Dick, the Baker, Geologist, and Botanist.—S. Smiles | 89 |

| 134, 135. | The Gospel of Work.—Charles Kingsley | 90, 91 |

| 136, 137. | Do not be Ashamed of your Origin.—Anecdotes | 92 |

| 138. | Not Near Enough Yet.—Rev. Prof. Earle | 93 |

| 139. | A Great Loss.—S. Smiles | 95 |

| 140, 141. | Hero Worship.—Charles Kingsley | 95, 96 |

| 142-144. | James Watt and the Steam-Engine.—Lord Jeffrey | 97, 98 |

| 145. | Manufactures in England.—Bevan | 98 |

| 146, 147. | Mr. H. M. Stanley’s Appeal for Supplies | 99, 100 |

| 148. | Answer to the preceding letter.—J. W. Harrison | 101 |

| 149, 150. | Mr. Stanley’s Acknowledgment of the preceding letter and the Supplies | 102, 103 |

| 151. | Returned Kindness.—Dr. Dwight | 104 |

| 152-154. | New-Year’s Eve.—After Hans Andersen | 105-107 |

| 155. | Providence Vindicating the Innocent.—W. Smith | 108 |

| 156, 157. | Napoleon Bonaparte.—Emerson | 109-111 |

| 158. | The Warlike Character of the Germans.—Admiral Garbett | 112 |

| 159. | The Way to Master the Temper.—Alcott | 113 |

| 160, 161. | Opinions as to English Education.—S. Smiles | 113-115 |

| 162. | A Royal Judgment.—P. Sadler | 116 |

| 163. | Tacitus.—Sir Walter Scott | 117 |

| 164. | Humility.—Anonymous | 117 |

| 165-168. | Russian Political Prisoners in Banishment.—James Allen | 118-122 |

| 169-171. | Tahiti.—Charles Darwin | 123-125 |

| 172. | Audubon, the American Ornithologist, relates how nearly a thousand of his original Drawings were destroyed.—John Audubon | 126 |

| 173-177. | The Battle of Kassassin.—The Correspondent of the London “Standard” | 127-132 |

| 178. | How the Duke of Wellington was Deceived.—Historical Anecdotes | 134 |

| 179-181. | A Letter from Dr. Henry Danson to Mr. John Forster, on Charles Dickens’s School-Life | 135-137 |

| 182. | Sir Joseph Paxton.—S. Smiles | 138 |

| 183-186. | Rebecca describes the Siege of Torquilstone to the wounded Ivanhoe.—Sir Walter Scott | 139-143 |

| 187-190. | The Favourite Hares.—William Cowper | 144-146[xvi] |

| 191. | Prince Bismarck’s Home.—The Correspondent of the London “Daily News” | 147 |

| 192. | Royal Benevolence.—W. Buck | 148 |

| 193. | Telegraphy among Birds.—Prof. G. Wilson | 149 |

| 194-196. | The Hanse.—J. H. Fyfe | 150-152 |

| 197. | Coming to Terms.—The “Young Ladies’ Journal” | 153 |

| 198. | False Pride.—The “New York Herald” | 155 |

| 199. | Anecdotes of Great Statesmen: | |

| I. Abraham Lincoln.—The “New York Herald” | 156 | |

| II. Prince Bismarck and Lord Beaconsfield.—The Correspondent of the London “Daily Telegraph” | 156 | |

| 200. | The Power of Music.—Manchester “Tit-Bits” | 158 |

| 201-206. | The two Schoolboys, or Eyes and No Eyes.—Dr. Aikin | 159-165 |

| 207, 208. | The King and the Miller.—Chambers’s Short Stories | 166, 167 |

| 209, 210. | A Friend in Need.—Chambers’s Short Stories | 168, 169 |

| 211. | My First Guinea.—The Rev. Dr. Vaughan | 169 |

| 212. | The Green Vaults in Dresden.—Bayard Taylor | 171 |

| 213. | The Death of Little Nell.—Charles Dickens | 172 |

| 214. | The Childhood of Robert Clive.—Lord Macaulay | 173 |

| 215, 216. | An Adventure with a Lion.—Dr. Livingstone | 173, 174 |

| 217-220. | The Burning of Moscow.—Sir Walter Scott | 175-177 |

| 221-223. | Christmas in Germany.—Bayard Taylor | 178-180 |

| 224. | New-Year’s Eve in Germany.—Bayard Taylor | 181 |

| 225, 226. | The Two Robbers.—Dr. Aikin | 182 |

| 227, 228. | A Touching Scene at Sea.—Rev. E. Davies | 183, 184 |

| 229-232. | An Oration on the Power of Habit.—J. B. Gough | 185-187 |

| 233-242. | A Curious Story.—W. J. J. Spry | 187-194 |

| 243, 244. | How the Bank of England was Humbled.—“Tit-Bits” | 195, 196 |

| 245, 246. | Morgan Prussia.—King George the Fourth | 197, 198 |

| 247. | The Terrible Winter of 1784.—After Alexander Dumas | 199 |

| 248-250. | A Story Worth Reading.—St. James’s Magazine | 201, 203 |

| Appendix: | ||

| A.—Essentials of Construction | 205 | |

| B.—The Indicative Mood | 209 | |

| C.—The Subjunctive (or Conjunctive) Mood | 210 | |

| D.—The Conditional Mood | 213 | |

| Synopsis of the changes the German Spelling has undergone through the Government Regulations of 1880 | 215-222 | |

| Index to the Grammatical Rules and Idiomatic Renderings | 223-228 | |

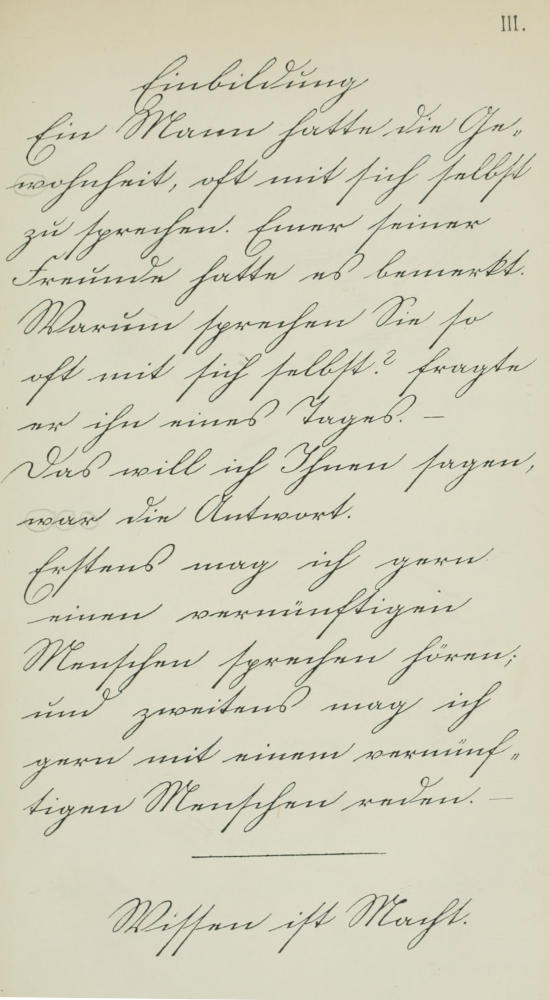

I.

II.

III.

IV.

[1]

1. Words which, in the English text and in the periphrases of the English text, are printed in Italics, must not be translated.

2. When two words are separated by a dash (—) in the Notes, they represent the first and last word of a whole clause in the English text, and the rendering refers to the clause thus indicated.

3. When two or more words are separated by dots (...) in the Notes, the rendering refers to those words only.

4. The sign = is used in the meaning of: ‘is equivalent to’.

5. As a rule, the periphrases are given in correct English construction.

My maxim is: never to begin[2] a book without finishing[3] it, never to consider[4] it finished without[5] knowing it, and to study[6] it with[7] a whole mind.—Sir Thomas Buxton.

[1] Grundsatz, m.

[2] to begin, an´fangen. When the Infinitive is used either subjectively or objectively, it is generally preceded by the preposition zu, and is called Supine. Comp. S. 78, N. 14, 1. To form the Supine Present of compound separable verbs, like an´fangen, we must place the preposition zu between the separable prefix and the verb. The Supine must be used here. See App. § 1.

[3] to finish, beendigen. The Supine is generally used for rendering the English Gerund (i.e. the verbal in -ing) when the latter is governed by a preposition, though, sometimes, this form may be rendered by the help of the subordinative conjunction daß and a finite verb (i.e. one with a personal termination); as—

| He judges without understanding anything about the matter. | Er urteilt, ohne etwas von der Sache zu verstehen, or ohne daß er etwas von der Sache versteht. |

Use the Supine, which is always to be placed at the end of the clause.

[4] To consider a thing finished, eine Sache als beendigt betrachten. The pronoun ‘it’ should begin the clause. See App. § 2.

[5] without — it, ohne mit dem Inhalt desselben vertraut zu sein.

[6] to study, studie´ren.

[7] with — mind = with undivided attention.

The following question was[1] put in writing[2] to a boy[3] in the deaf-and-dumb school[4] at Paris: “What is eternity?” “It is the life-time of the Almighty,” was the answer.—Rev. R. K. Arvine.

[2]

[1] Here the verb is in the Passive Voice. Remember that the German Passive Voice is formed by the auxiliary werden. The verb is in the Passive Voice whenever the subject is suffering the action expressed by the verb; as—

| The castle was built in the year 1609. | Das Schloß wurde im Jahre 1609 erbaut. |

To put a question to a person, einem eine Frage vor´legen.

[2] in writing, schriftlich, which place before the p. p. (App. § 1).

[3] boy = pupil.

[4] Taubstummenanstalt, f.; render ‘in the’ by the gen. of the def. art.; at = in.

The action of water on[3] our food[4] is very important. There[5] would be no carrying of food into the system but for the agency of water. It dissolves everything[6] that[7] we take[8], and nothing[9] that we take as food can[10] become nutriment that[11] is not dissolved in water.—Dr. Lankester.

[1] ‘action’, here = operation, Wirkung, f.

[2] Use the gen. of the def. art. The definite article is always required before nouns representing the whole of a given class, and before abstract nouns taken in a general sense.

[3] on = upon.

[4] food = victuals, Speisen, pl.

[5] This sentence must be construed in a somewhat different way; say: ‘Without the agency (Vermittelung, f.) of water, no food (Nahrung, f.) would be conveyed into the body,’ würde dem Körper keine Nahrung zu´geführt werden.

[6] everything = all.

[7] ‘that’, here was. The indefinite relative pronoun was is the pronoun generally required after the indefinite numerals alles, etwas, manches, nichts, viel, and wenig, after the indefinite demonstrative pronoun das, and also after a superlative used substantively; as Das Schönste, was ich habe.

[8] ‘To take’, when used of food, may be rendered by essen, trinken, or genießen, which latter verb should be used here.

[9] ‘nothing — food’, may be briefly rendered by ‘keine genossene Speise‘.

[10] can — nutriment = can serve as nutriment (Ernährung, f.). The verb dienen requires the prep. zu, which governs the dat. and must here be contracted with the def. art. into zur: see N. 2.

[11] that — water = before (ehe, see App. § 17) the same (f.) is dissolved in water.

When[2] Franklin made his discovery of the identity[3] of lightning[4] and electricity[4], it[4] was sneered at[5], and people asked: “Of what use is it?” To[6] which his apt reply was: “What is the use of a child?—It may[7] become a man!”—S. Smiles.

[1] Of — it, Wozu nützt es?

[2] ‘When’, referring to definite time of the Past, must always be rendered by ‘als’.

[3] of the identity, von der Identität, f.; see S. 3, N. 2.

[4] When the agent from which the action proceeds is not mentioned, the English Passive Voice is often rendered by a reflective verb, or by the indefinite pronoun man and a verb in the Active Voice; as—

| At last the book was found. | Endlich {fand sich} das Buch. |

| {fand man} |

Say ‘people (man) sneered at it.’

[3]

[5] A. To sneer at something, über etwas spotten; B. ‘at it’ = there at, darüber. The English pronouns ‘it’, ‘them’, ‘that’, and ‘those’, dependent on a preposition governing in German the dative or accusative, are generally to be rendered by the pronominal adverb ‘da’ in combination with a corresponding preposition. This is always the case when ‘it’ and ‘that’, in connection with a preposition are used indefinitely, and frequently when either of these pronouns refers to a noun representing an inanimate object or an abstract idea. The letter r is inserted between the adverb da and the preposition, whenever the latter begins with a vowel.

[6] To — was = Upon this (Hierauf) he (inverted constr., see App. § 14) gave the following striking (treffend) answer.

[7] may = can; to become a man, zum Manne werden.

Wealth, after all[2], is[3] but a relative thing: for he who has[4] little, and wants[5] still less, is richer than he who has much, and wants still more.—Rev. C. Cotton.

[1] wealth, Reichtum, m., see S. 3, N. 2.

[2] after all ... but, doch immer nur; a — thing, etwas Relatives.

[3] When the subject, which may be preceded by its attributes, occupies the first place in a principal clause, either the copula or the verb must follow immediately.

[4] to have = to possess.

[5] ‘to want’, here bedürfen.

When[1] Mendelssohn, on[2] the first performance of his[3] ‘Elijah’ in Birmingham, was about[4] to enter[5] the orchestra, he[6] said laughingly to one of his friends and critics[7]: “Stick[8] your claws into me! Don’t tell[9] me what you like, but[10] what you don’t like!”—Athenæum.

[1] See S. 4, N. 2.

[2] The preposition ‘on’, signifying ‘on the occasion of’, must be rendered by ‘bei’. ‘Performance’, Aufführung, f.

[3] Use the gen. of the def. art.; Elijah, Elias.

[4] ‘to be about’, im Begriff sein. ‘To be about’ may also be rendered by the auxiliary verb of mood wollen and the infinitive of another verb; as—

| I was just about to leave, when the letter arrived. | Ich war gerade im Begriff abzureisen (or Ich wollte gerade abreisen), als der Brief ankam. |

[5] ‘to enter’, betreten, see S. 1, N. 2.

[6] Since the subordinate clause precedes the principal clause, the construction of the principal clause must be inverted, see App. § 15.

[7] to — critics, say ‘to a friend and critic’, Rezensent, m.

[8] ‘Stick — me!’ This metaphor must be rendered freely by: Packen Sie mich nur tüchtig an!

[9] tell = say; to like = to please, with the dat. of the person.

[10] The co-ordinative conjunction ‘but’ must be rendered by ‘sondern’, when, after a negative statement, the subsequent clause expresses an idea altogether contrary to that of its antecedent.

“I can forgive, but I cannot forget,” is[2] only another way of saying: “I will not forgive.” A wrong once forgiven[3] ought[4] to be like[5] a cancelled note[6], torn in two and burned up, so[7] that it never can be shown against the man.—Rev. H. W. Beecher.

[4]

[1] ‘to be’, here = to signify, heißen.

[2] is — saying = signifies only in (mit) other words. ‘Das Wort’ has two plural forms with a different meaning to each: die Wörter, single, unconnected words; die Worte, words connected into speech.

[3] A. Whilst the English Perfect Participle (commonly called Past Participle) is placed both before and after the noun it qualifies, the German Past Participle used attributively, as a rule, precedes the qualified noun; as—

| We met with a ship bound for Bremen. | Wir trafen ein nach Bremen bestimmtes Schiff. |

B. Clauses containing a Perfect Participle, however, may also be rendered by the help of a relative pronoun. Thus rendered, the preceding sentence would read:

Wir trafen ein Schiff, welches nach Bremen bestimmt war;

but the first rendering is certainly more concise than the second, and it is to be preferred in all cases where the attributive construction would not be too lengthy. ‘A wrong once forgiven’, say ‘A forgiven wrong’, and mark that: When Participles are used attributively, and precede the noun they qualify, they must be inflected like adjectives.

[4] render ‘ought’ by the imperfect of sollen.

[5] like, wie.

[6] note, Schuldschein, m.; to tear in two, zerrei´ßen; to burn up, verbren´nen. According to the rule given in N. 3, the participles of these two verbs have to be placed before the noun ‘note’, which they qualify.

[7] ‘so — man’, say ‘which never again can be used against the debtor’. According to the hint given in S. 2, N. 1, the verb is in the passive voice, and since the clause is a subordinate one, the verbs must stand at the end of the clause. Place the p. p. first, and the copula (can) last.

What is capital? Is[1] it what a man has? Is[2] it counted (App. § 31) by[3] pounds and pence, stocks[4] and shares[5], by houses and lands[6]? No! Capital[7] is not what a man has, but what a man is. Character[8] is[9] capital; honour[10] is capital.—Rev. Dr. Macduff.

[1] ‘Is — has?’ say ‘Does it consist in that which (see S. 3, N. 7) we possess?’ The prep. ‘in’ here governs the dat. Read again S. 4, N. 5, B, and notice that, when the demonstrative pronouns ‘that’ and ‘those’ are followed by a relative pronoun, they cannot be rendered by the adverb ‘da’ in combination with a preceding preposition; as—

| We laughed at that which (or at what) you told us. | Wir lachten über das, was Sie uns erzählten. |

[2] See S. 2, N. 1; ‘to count’, here schätzen.

[3] by = nach.

[4] Wertpapiere.

[5] Aktien.

[6] Ländereien.

[7] ‘Capital — is’. The literal translation of this sentence would read very awkwardly in German, say ‘Our capital does not consist in that which we possess, but (S. 6, N. 10) in that which we are.’

[8] Character = A good reputation.

[9] ‘is’, here ist.

[10] Ehrenhaftigkeit, f.

A French minister, who was alike[2] remarkable[3] for his[4] despatch of business and his constant[5] attendance at places of public amusement, [5]being[6] asked how he contrived to combine both objects, replied: “Simply[7] by never postponing till to-morrow what should be done[8] to-day.”—S. Smiles.

[1] Lebensregel, f.

[2] ‘alike ... and’, sowohl ... wie auch.

[3] to be remarkable for something, sich durch etwas aus´zeichnen.

[4] his — business, schnelle Erledigung seiner Amtsgeschäfte.

[5] constant — amusement, regelmäßiger Besuch öffentlicher Vergnügungsorte. The prep. durch, which requires the acc., must be repeated at the beginning of this clause.

[6] ‘being — replied’; this sentence requires an entirely different construction in German, say ‘answered upon the question, how (App. § 16) he made it possible to combine both (neuter sing.)’. To combine, vereinigen. The verb ‘to make’ must be placed in the Present Subjunctive, since the clause contains an indirect question. Read carefully App. §§ 28 and 30.

[7] Simply — to-morrow, Einfach dadurch, daß ich nie auf morgen verschiebe.

[8] ‘to do’, here erledigen. See S. 2, N. 1, and place the verbs in the order pointed out in S. 7, N. 7.

The peace, the freedom, the happiness[3], and the order which Victoria’s rule guarantees[4], are[5] part of my birthright as an Englishman, and I bless[6] God for my share[7]! Where else shall[8] I find such liberty[9] of action, thought, speech[10], or[11] laws which protect me so well[12]?—W. M. Thackeray.

[1] rule = reign.

[2] Use the gen. of the def. art. The definite article is used in German before names of persons when preceded by an adjective or a common name; as—

| Der arme Fritz! | Poor Fritz! |

| Der Kaiser Wilhelm. | Emperor William. |

[3] happiness = well-being, Wohlfahrt, f. ‘Victoria’s rule’, say ‘the reign of Queen Victoria’.

[4] to guarantee, gewähren.

[5] are part = form a part.

[6] I bless = I thank.

[7] share = lot.

[8] shall = can.

[9] Freiheit des Handelns. Repeat the article before the two following nouns. In German the articles, possessive adjective pronouns, and other determinative words must be repeated when they are used in reference to several nouns of different gender or number, whilst in English they are only required before the first noun.

[10] Insert ‘and’ before ‘speech’, Rede, f., and place the verb finden immediately after that noun.

[11] Substitute the words ‘and where’ for the word ‘or’.

[12] gut.

The weakest living creature[1], by[2] concentrating his powers on a single object, can[3] accomplish something. The strongest[4], by dispersing his over many, may fail to accomplish anything[5]. The drop, by continually[6] falling[7], bores[8] its passage through the hardest rock. The hasty[9] torrent rushes[10] over it with hideous uproar, and leaves no trace behind.—T. Carlyle.

[1] creature, Wesen, n.; strengthen the superlative of the adjective by placing ‘aller’ before it, forming one compound expression, analogous to: Die aller schönste Blume, the finest flower (of all).

[6]

[2] ‘by concentrating his powers’, durch Konzentration seiner Kräfte; to accomplish something, etwas zustande bringen. Use the adverbial expression ‘at least’ before ‘something’, which will give more force to the German rendering.

[3] The copula ‘can’ must be placed immediately after the subject and its attributes, as has been pointed out in S. 5, N. 2.

[4] The strongest — fail, Dem Stärksten hingegen wird es durch Zersplitterung seiner Kräfte nicht gelingen.

[5] anything, auch nur das Geringste.

[6] continual, unablässig, adj.

[7] To render ‘falling’, form a noun of the verb ‘fallen’. The German language makes frequent use of the Infinitive Present of verbs to form abstract nouns, whilst the English language uses the Verbal in -ing for that purpose. Such nouns are always of the neuter gender; as das Gehen, going; das Essen und Trinken, eating and drinking.

[8] to bore one’s passage, sich einen Weg bohren. Place the verb according to S. 5, N. 2; the adverbial clause ‘by continually falling’ must follow it.

[9] hasty, ungestüm; torrent, Strom, m.

[10] to rush over something, über etwas hinweg´stürzen; ‘rushes — uproar’, say ‘rushes with hideous (entsetzlich) uproar (Getöse) over the same.’

Of the Duke of Wellington’s[2] perfect coolness on[3] the most trying occasions. Colonel Gurwood gives[4] this instance. He was[5] once in great danger of suffering[6] ship-wreck. It was bed-time[7] when (S. 4, N. 2) the captain of the vessel came to him, and said: “It will soon be all over[8] with us!” “Very well,” answered the Duke, “then I (App. § 14) need not (App. § 12) take off[9] my boots!”—W. C. Hazlitt.

[1] Kaltblütigkeit, f.

[2] Place the genitive after the governing noun, and say: ‘Of (Von) the perfect coolness of the Duke of Wellington.’ Perfect = great.

[3] ‘on — occasions’ = in the most dangerous (gefahrvoll) situations.

[4] to give = to relate. See App. § 14 for the construction. ‘This instance’ = the following example.

[5] ‘to be’, here sich befinden.

[6] Construe according to S. 1, N. 3.

[7] Schlafenszeit, f.

[8] vorüber.

[9] to take off, aus´ziehen, see S. 1, N. 2.

When[2] certain persons attempted[3] to persuade Stephen[4], King of Poland, to constrain[5] some of his subjects, who[6] were of a different religion, to embrace[7] his, he said[8] to them: “I[9] am king of men, and not of[10] consciences[11]. The[12] dominion of conscience belongs exclusively to God.”—Rev. R. K. Arvine.

[1] Religionsduldung, f.

[2] ‘When’, here?

[3] attempted to = would, impf. of wollen.

[4] Say ‘the king Stephen of Poland’. König Stephan von Bathori regierte von 1576-1586.

[5] zwingen. Place the verb after the relative clause, since the relative pronoun should follow its antecedent as closely as possible.

[6] ‘who — religion’, say ‘who belonged to another religion’.

[7] to embrace = to accept.

[8] ‘to say’, here ‘to reply’, entgegnen.

[9] I — men = I rule (herrschen) over men.

[10] of = over.

[11] This noun is not used in the plural in German. See S. 3, N. 2.

[12] ‘The — God’, say ‘God alone rules over consciences (sing.)’.

Hugh Miller’s[3] curiosity[4] was[5] excited by the remarkable traces of extinct[6] sea-animals in[7] the Old Red Sandstone, on which he worked as a quarryman. He inquired[8], observed, studied, and became a geologist. “It was the necessity”, said he, “which made[9] me a quarrier, that taught me to be a geologist.”—S. Smiles.

[1] Hugh Miller wurde am 10ᵗᵉⁿ Oktober 1802 von armen Eltern zu Cromarty in Schottland geboren. Er arbeitete 15 Jahre als gemeiner Steinbrecher, beschäftigte sich jedoch während jener Zeit mit litterarischen und wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten, besonders mit der Geologie, der er ganz neue Bahnen eröffnete. Durch seine Werke hat er sich in der Wissenschaft einen unsterblichen Namen erworben, und als er am 24ˢᵗᵉⁿ Dezember 1856 starb, verlor Schottland in ihm einen seiner besten Söhne, und die Geologie einen ihrer beredtesten und ergebensten Lehrer.

[2] Contrary to English construction, the indefinite article is not used in German in stating the business or profession of a person; as—

| He wants to be a soldier. | Er will Soldat werden. |

Exception: When the noun denoting the business or profession is preceded by an adjective, the indefinite article is used in German, as in English:

| His father was a clever physician. | Sein Vater war ein geschickter Arzt. |

[3] When a Proper Name is used in the Genitive Case, it is generally placed before the governing noun, as in English: Schiller’s poems, Schillers Gedichte.

[4] Wißbegierde, f.

[5] How is the Passive Voice to be recognised? ‘To excite’, here lebhaft an´regen; construe accord. to S. 13, N. 5.

[6] aus´gestorben.

[7] in — sandstone, in einem alten Rotsandsteinlager; on which = where.

[8] ‘to inquire’, here Nachforschungen anstellen.

[9] ‘to make’ requires here the prep. zu contracted with the def. art.; ‘that — geologist’, machte mich schließlich auch zum Geologen.

When Diogenes, during the famous festival[2] at Olympia[3], saw[4] some young men of Rhodes arrayed[5] most magnificently, he (App. § 15) exclaimed smiling: “This is pride!” And when, afterwards[3], he met[6] with some Lacedæmonians in a mean[7] and sordid[8] dress, he said: “And this is also pride!”—Rev. R. K. Arvine.

[1] Die Extreme berühren sich.

[2] the festival at Olympia, die Olympischen Feste. Diese berühmten Feste, auch Olympische Spiele genannt, wurden in jedem fünften Jahre am ersten Vollmond nach der Sonnenwende (Anfang Juli) bei Olympia zu Ehren des Zeus gefeiert. Sie dauerten fünf Tage und bestanden in Wettrennen (zu Wagen, zu Pferd und zu Fuß) und in gymnastischen Spielen aller Art.

[3] Contrary to English practice, the comma is, as a rule, not used in German to enclose adverbs or adverbial clauses of time, manner, and place.

[4] ‘to see’, here erblicken, which place after ‘Rhodes’; young men = youths; ‘of’, here aus; Rhodes, Rhodus.

[5] ‘arrayed — magnificently’. Turn these words into a relative clause, and say: ‘which were most magnificently (aufs prächtigste) arrayed (schmücken)’, according to the rule given in S. 7, N. 3, B.

[6] to meet with a person, einem begegnen. Place the subject immediately after ‘when’. The Lacedæmonian, der Lazedämonier.

[7] armselig.

[8] zerlumpt.

[8]

When the Duke of Marlborough, immediately after the battle of Blenheim[2], observed[3] a soldier leaning[4] pensively on the butt-end of his musket, he accosted[5] him thus: “Why so pensive[6], my friend, after so[7] glorious a victory?” “It may be glorious[8],” replied the brave fellow, “but[9] I am thinking that all the human blood I[10] have spilled this day[11] has only[12] earned me fourpence.”—Rev. R. K. Arvine.

[1] Armselige Bezahlung.

[2] Die Schlacht bei Blindheim (Engl. ‘Blenheim’) wurde am 13ᵗᵉⁿ August 1704 von dem Herzog von Marlborough in Verbindung mit dem östereichischen Prinzen Eugen gegen die Franzosen gefochten. Blindheim ist ein kleines bayerisches Dorf bei Höchstädt, an der Donau. Die Schlacht wurde zu gunsten der Verbündeten entschieden, und der Herzog von Marlborough erhielt für diesen glänzenden Sieg von der Königin Anna ein prachtvolles Schloß (Blenheim House) bei Woodstock in Oxfordshire zum Geschenk.

[3] Place the verb ‘observed’ after the noun ‘soldier’.

[4] ‘leaning — musket’. This passage must be changed into a relative clause, thus: ‘who leant (sich stützen) pensively (gedankenvoll) upon the butt-end (Kolben, m.) of his musket’, for: Sentences containing a Present Participle which qualifies a preceding noun or pronoun, are generally turned into relative clauses; as—

| The teacher, noticing the boy’s talent, applied to the prince on his behalf. | Der Lehrer, welcher das Talent des Knaben bemerkte, verwendete sich für ihn bei dem Fürsten. |

[5] to accost, anreden; thus, folgendermaßen.

[6] here ‘nachdenkend’ in order to avoid the repetition of the same word.

[7] so ... a, ein ... so.

[8] Make the word ‘glorious’ emphatic by placing it at the head of the clause, and see App. § 14. Insert the adverb ‘wohl’ between the subject and the verb ‘be’, which will render the sentence more idiomatic.

[9] but — thinking, aber ich bedenke.

[10] Supply the relative pronoun ‘which’, for: The relative pronoun can never be omitted in German; to spill, vergießen.

[11] this day = to-day.

[12] This work has only earned me a shilling, diese Arbeit hat mir nur einen Schilling eingebracht.

We[1] may be pretty certain that persons[2] whom all the world treat ill, deserve entirely[3] the treatment they[4] get. The world is a looking-glass, and gives[5] back to every man the reflection of his own face. Frown[6] at it, and[7] it will in turn look sourly upon you; laugh[8] at it and with it, and[9] it is a jolly, kind companion[10].—W. M. Thackeray.

[1] We — certain. Wir können uns ziemlich sicher darauf verlassen.

[2] persons — ill = those who have to suffer from everybody.

[3] vollkommen.

[4] they get, welche ihnen zuteil wird.

[5] to give back the reflection = to reflect, zurück´werfen; every man, jeder; face = image.

[6] to frown at a person, here ‘einen mürrisch an´blicken’; use the second pers. sing.

[7] and — you, und sie wird auch auf dich verdrießlich hernie´derschauen.

[8] ‘Laugh at it’ seems to be used here in the sense of: ‘Smile at it’. Say: ‘Smile at it, laugh with it’, etc. ‘To smile at a person’, here ‘einen freundlich an´blicken’.

[9] ‘and — is’, say: ‘and it will be for thee (dir)’.

[10] Gefährtin.

[9]

A lady applied[2] to the worthy philanthropist[3] Richard Reynolds on behalf of a little orphan boy. After he[4] had (App. § 17) given liberally[5], she said: “When[6] he is old enough, I (App. § 15) will teach[7] him to thank his benefactor.” “Stop[8],” said the good man, “thou art mistaken[9]. We do not thank the clouds for rain (S. 3, N. 2). Teach[10] him to look higher, and thank Him[11] who giveth both the clouds and the rain.”—Rev. R. K. Arvine.

[1] Say ‘Give God alone the honour’.

[2] to apply to a person on behalf of somebody, sich bei einem für jemand verwenden.

[3] Menschenfreund, m.

[4] To avoid ambiguity turn the pron. ‘he’ here by ‘Reynolds’.

[5] ‘liberally’, here reichlich.

[6] The conjunction ‘when’, used in the sense of ‘whenever’, and referring to indefinite time, must be rendered by ‘wenn’ (compare S. 4, N. 2); as—

| When (whenever) my old teacher came to Hamburg, he always stayed with me. | Wenn mein alter Lehrer nach Hamburg kam, wohnte er stets bei mir. |

[7] The verb ‘lehren’, to teach, requires the accusative of the person. Render the sentence ‘I — benefactor’ by ‘I will teach him to be thankful to his benefactor’.

[8] Halt´!

[9] to be mistaken, sich irren.

[10] Teach — higher, Lehre ihn höher blicken.

[11] The pronoun ‘Him’ is here used as a demonstr. pron.; ‘both ... and’, sowohl ... wie auch; ‘to give’, here = to send.

When young (S. 10, N. 2) Cuvier was one day[2] strolling[3] along the sands near Fiquainville, in Normandy[4], he observed a cuttle-fish lying[5] stranded on the beach. He was attracted[6] by the curious object, took it home to[7] dissect, and[8] began the study of the mollusca, which ended in his becoming one of the greatest among natural historians.—S. Smiles.

[1] G. D. Cüvier, berühmter französischer Naturforscher (1769-1832), erhob die vergleichende Anatomie zuerst zur Wissenschaft.

[2] one day, eines Tages; one morning, eines Morgens; one evening, eines Abends, etc.

[3] to stroll along the sands, an der Küste umher´schlendern, ‘near’, here von.

[4] die Normandie, always used with the def. art.

[5] ‘lying — beach’, say ‘which the sea had washed (spülen) upon the beach’. (See App. § 17.)

[6] to be attracted by something, sich durch etwas an´gezogen fühlen; ‘object’, here ‘creature’.

[7] The Supine is used to express purpose, and must be employed whenever the English ‘to’ is used in the meaning of ‘in order to’, or ‘for the purpose of’; clauses of this sort are generally introduced by the conjunction ‘um’; as—

| I will take this animal home to dissect. | Ich will dies Tier mit nach Hause nehmen, um es zu sezieren. |

[8] ‘and — historian’, say ‘began (an´fangen) to study the mollusca, and became finally (schließlich) one of the greatest natural historians’. Mollusca, Mollusken or Weichtiere.

[10]

In literature (S. 3, N. 2) I am fond[2] of confining myself to the best company, which consists chiefly of old acquaintances[3] with whom I am desirous of becoming more intimate, and I suspect[4] that, nine[5] times out of ten, it is more profitable[6], if not more agreeable, to read an old book over again, than[7] to read a new one for the first time.—Lord Dudley.

[1] ‘of books’, here der Lektüre.

[2] A. The verbs ‘to be fond of’ and ‘to like’ are often rendered by the auxiliary verb of mood ‘mögen’, either with or without the adverb ‘gerne’ or ‘gern’ (willingly), which is used to intensify its signification; as—

| I am very fond of the German language. | Ich mag die deutsche Sprache sehr gern. |

| Are you fond of walking? | Mögen Sie gerne spazieren gehen? |

| I don’t like this child. | Ich mag dies Kind nicht. |

B. But the adverb gerne or gern in itself denotes liking and fondness, and is therefore the general translation of the verbs ‘to be fond of’ or ‘to like’ when used with the infinitive of other verbs; as—

| I like to dance. | Ich tanze gern. |

| We are fond of confining ourselves to a few old books. | Wir beschränken uns gern auf einige wenige alte Bücher. |

Construe the above clause accord. to the last example given.

[3] acquaintances = friends; I am desirous of becoming = I wish to become (App. § 19). The insertion of the adverb ‘noch’ before the comparative will greatly improve the rendering of this clause.

[4] to suspect = to believe.

[5] ‘nine times out of ten’ may be briefly rendered by the adverbial expression meistenteils, which place immediately after the subject of the subordinate clause.

[6] profitable, nützlich; ‘if — agreeable’, say ‘if not even (gar) more agreeable’; ‘over again’, here noch einmal.

[7] ‘than — time’, say ‘than to occupy oneself (sich beschäftigen) with a new one’. This periphrase is necessary to avoid a monotonous repetition in German.

When Galvani[3] discovered that a frog’s leg[4] twitched when placed in contact with different metals, it[5] could scarcely have been imagined that so apparently insignificant a fact would ever lead (App. § 17) to important results. Yet therein lay the germ of[6] the Electric Telegraph, which[7] binds the intelligence of continents together, and probably before many years elapse will[8] “put[9] a girdle round the globe.”—S. Smiles.

[1] Thatsache, f.

[2] See S. 5, N. 2, and place the adverb after the verb; ‘result’, Resultat, n.

[3] Luigi Galvani, italienischer Anatom, entdeckte 1780 den Galvanismus. ‘When — discovered’, say ‘When Galvani made the discovery’.

[4] ‘leg’, here Schenkel, m.; to twitch, in Zuckungen geraten; when placed = when (S. 18, N. 6) the same was (S. 2, N. 1) brought.

[5] it — imagined, hätte man sich kaum vorstellen können; ‘that so apparently ... a’, daß eine scheinbar so.

[6] zum.

[7] which — together, welcher die Geister der Kontinente mit einander verbindet; before — elapse = in a few years.

[9] to put a girdle round the globe, einen Gürtel rings um die Erde ziehen. ‘Rings um die Erde zieh’ ich einen Gürtel in viermal zehn Minuten.’ Puck, Sommernachtstraum.

[11]

Oats are (S. 2, N. 1) chiefly used whole[2] as food for horses. Ground[3] into meal, they are used in some countries (especially in Scotland) for[4] making porridge and cakes. As[5] a plant, it is extremely hardy, and grows where neither wheat nor barley could[6] be made productive. For[7] this reason it is a favourite crop in mountainous countries and moist climates—for example in Scotland and Wales. It (S. 5, N. 2) also grows luxuriantly in Australia, Northern[8] and Central Asia, and in North America.—Nelson’s Readers.

[1] Der Hafer, which noun is never used in the plural.

[2] whole, ungemahlen; to use, benutzen; food for horses, Pferdefutter, n.

[3] Ground — meal, zu Mehl vermahlen; they — used = one uses (gebrauchen) it (m.). see S. 4, N. 4; ‘country’, here Gegend.

[4] for — cakes, um Mehlsuppe und Kuchen daraus zu machen.

[5] ‘As — hardy’, say ‘The plant is extremely hardy (kräftig)’.

[6] could — productive = would thrive.

[7] For — reason, Daher, adv., App. § 14. Render the pron. ‘it’ by ‘der Hafer’; a favourite crop, das Hauptgetreide.

[8] in Nord- und Mittelasien.

The blossoms of Spring are as brief[2] as they are beautiful. For[3] a short time they embellish the country, spreading[4], as it were, a bridal veil over every[5] tree and hedge. It seems, indeed[6], as if Nature had given them existence only to (S. 19, N. 7) show their worth, and then to destroy them. Yet[7] they are “fair pledges of a fruitful tree,” and teach us the solemn[8] lesson—that[9] everything lovely on earth is destined soon to perish, and[10] like them to glide into the grave.—Rev. E. M. Davies.

[1] Frühlingsblüten.

[2] vergänglich.

[3] Auf; to embellish, schmücken.

[4] spreading = and spread; as it were, gleichsam.

[5] ‘every — hedge’, say ‘hedges and trees’.

[6] wirklich; as — only, als hätte die Natur ihnen nur das Dasein verliehen.

[7] ‘Yet — tree’, say ‘They are however the lovely messengers (Vorboten) of a fruitful (fruchtreich) tree’.

[8] solemn lesson, ernste Wahrheit.

[9] that — perish, daß alles Schöne auf Erden der Vergänglichkeit geweiht ist.

[10] ‘and — grave’, say ‘and like the blossoms must (App. § 18) glide (sinken) into an early grave’.

The[2] object of winking is a very important one. An outside[3] window soon (S. 5, N. 2) gets soiled[4] and dirty, and a careful shopkeeper[5] cleans his windows every morning. But our eye-windows must[6] never have so much as a speck or spot upon them; and the winking eyelid[7] is the busy apprentice who, not once a day, but[8] all the day, keeps the living glass[9] clean; so that, after all[10], we are little worse off than the fishes, who[11] bathe their eyes and wash their faces every moment.—Prof. G. Wilson.

[12]

[1] Das Öffnen und Schließen der Augenlider.

[2] ‘The — one’, say ‘The opening and closing of the eyelid (pl.) is of great importance.

[3] outside window = street window.

[4] trübe.

[5] Ladenhüter; supply the adv. ‘therefore’ after the verb ‘cleans’, and place the object last of all.

[6] ‘must — them’, say ‘must (dürfen) never suffer (erleiden) even (selbst) the smallest speck, the least dimness (Trübung).

[7] das sich öffnende und schließende Augenlid; ‘apprentice’, here Ladenbursche.

[8] but — day, nein, den ganzen Tag hindurch.

[9] Augenglas.

[10] genau betrachtet; the subject should be placed immediately after the conjunction ‘that’; little = not much; to be badly off, schlimm daran sein.

[11] who — moment, welche Augen und Gesicht jeden Augenblick baden und waschen.

It is reported that, one day (S. 19, N. 2), the[1] two great philosophers Aristippus[2] and Æschines had fallen at variance[3]. The[4] following day, however, Aristippus came to[5] Æschines, and said: “Shall[6] we be friends?” “Yes, with[7] all my heart!” answered Æschines. “Remember[8],” continued Aristippus, that[9] though I am your elder, yet I sought for peace. “True[10],” replied Æschines, “and for this[11] I will always acknowledge you to be the more worthy man, for[12] I began the strife, and you the peace.”—Rev. J. Burroughs.

[1] Place the subject immediately after the conj. ‘that’.

[2] Aristippus aus Cyrene wurde (380 v. Chr.) Stifter der cyrenaischen Philosophenschule, welche die Lehre aufstellte, daß das höchste Glück des Menschen im sinnlichen und geistigen Vergnügen zu suchen sei. Aristippus war ein Zeitgenosse des Socrates und der einzige Philosoph seiner Zeit, der sich seine Vorträge mit Geld bezahlen ließ. Äschines war ein Nebenbuhler und Gegner des Demostenes, wurde (389 v. Chr.) zu Athen geboren, lebte später zu Rhodus und siedelte endlich nach Samos über, wo er (314 v. Chr.) starb.

[3] to fall at variance, sich überwer´fen.

[4] The = On the; however, jedoch, which must not be placed between commas.

[5] Use here the def. art. contracted with the prep. zu into zum, for: The def. art. is often used to mark the Gen. Dat. and Acc. of proper names.

[6] Shall = Will.

[7] von ganzem Herzen!

[8] Erinnere dich daran.

[9] Say ‘that I have sought for peace, although I am the elder’; to seek for peace, um den Frieden nach´suchen.

[10] Say ‘That is true’.

[11] deshalb, adv. (App. § 14). He acknowledged you to be the more worthy man (of us two), Er erkannte dich als den Würdigeren von uns beiden an; construe according to this example, and supply the expletive ‘auch’ after the object ‘you’.

[12] denn ich war der erste zum Streit, und du zum Frieden.

I must now explain to you[1] what a glacier is. You see before you[2] thirty or forty mountain-peaks, and between these peaks what[3] seem to you frozen rivers. The snow, from[4] time to time melting and dripping down the sides of the mountain, and congealing in the elevated hollows between the peaks, forms a half-fluid mass, a river of ice[5], which is called (S. 4, N. 4) a glacier. As[6] the whole mass lies upon a slanting surface, and is not entirely solid throughout, it[7] is continually pushing, with a gradual but imperceptible motion, down[8] into the valley below.—Mrs. Beecher Stowe.

[13]

[1] Use the 2nd pers. sing.

[2] Place the words ‘before you’ after the object.

[3] glaubst du zu Eis erstarrte Flüsse zu erblicken.

[4] which (App. § 16) from time to time melts, drips down on the mountain-sides (Bergabhänge), and congeals (gefrieren), etc., see S. 16, N. 4. Supply the adverb wieder before the verb ‘congeals’. The elevated hollow, die höher gelegene Felsspalte.

[5] Eisstrom, m.

[6] As = Since, da (App. § 16); to be entirely solid throughout, durch und durch fest sein.

[7] it — pushing, so senkt sie sich fortwährend; with a ... but, mit einer zwar ... doch.

[8] down — below, in das unten liegende Thal hinab.

It was one of the characteristic qualities of Charles James Fox[2], that[3] he was thoroughly pains-taking in all that he did. When[4] appointed Secretary of State, being[5] piqued at some observation as to his bad writing, he actually took[6] a writing-master, and wrote copies like a schoolboy until he had sufficiently improved himself. Though[7] a corpulent man, he[8] was wonderfully active at picking up tennis-balls, and[9] when asked how he contrived to do so, he playfully replied: “Because[10] I am a very pains-taking man.” The same accuracy which he bestowed upon trifling matters[11], was displayed by him in things of greater importance; and[12] he acquired his reputation by “neglecting nothing.”—S. Smiles.

[1] Ohne Mühe kein Gewinn.

[2] Ich möchte vorschlagen zu übersetzen: ‘of the famous Ch. J. Fox’, weil dadurch das Verhältnis des Genitivs ganz klar ausgedrückt wird. Charles James Fox (1749-1806) ward schon 1768 Mitglied des Unterhauses, 1772 Lord des Schatzes, und bildete 1783 mit North und Portland ein Ministerium, welches jedoch bald dem Ministerium Pitt weichen mußte. Er begann darauf mit Burke und andern eine großartige parlamentarische Opposition gegen Pitt und kämpfte von 1792-97 fast allein gegen eine starke Majorität. Im Jahre 1806, kurz vor seinem Tode, wurde er mit Granville nochmals ans Staatsruder berufen.

[3] daß er sich in allem, was er that, die größte Mühe gab.

[4] When he was appointed (see N. 7). The verbs machen (to make), ernennen (to appoint), and erwählen (to choose, to elect), and other verbs denoting choosing or appointing, require in German the prep. zu contracted with the def. art., whilst in English they govern two Nominatives in the Passive Voice; as—

| Der Freund meines Vaters ist zum Abgeordneten erwählt worden. | My father’s friend has been elected a member of Parliament. |

[5] being — writing. This clause must be rendered in an altogether different form; let us say ‘and felt hurt by an observation as to (über) his bad hand-writing’. To feel hurt by something, sich durch etwas verletzt fühlen. The p. p. must be placed?

[6] ‘to take’, here engagie´ren; ‘actually’, here faktisch (see App. § 15); to write copies, sich im Schönschreiben üben; improved himself = improved his hand-writing.

[7] Though he was. Grammatical distinctness, as a rule, requires that the subject and copula, which after certain conjunctions are so frequently omitted in English, should be clearly expressed in German.

[8] When a subordinate clause, beginning with one of the conjunctions da, obgleich, weil, and wenn, precedes a principal clause, which is often done for the sake of emphasis, the principal clause is generally introduced by the adverbial conjunction so (so, thus, therefore); as—

| Da es regnet, so können (App. § 15) wir nicht ausgehen. | As it is raining, we cannot go out. |

‘He — balls’, so war er im Auffangen der Bälle beim Tennisspiele doch merkwürdig gewandt.

[14]

[9] ‘and — so’, say ‘and when (S. 18, N. 6) one asked him how he did (machen) it’. The verb machen should be used in the Pres. Subj., since the clause contains an indirect question (App. §§ 28 and 30). Playfully, scherzend.

[10] Weil ich mir stets die größte Mühe gebe.

[11] trifling matters, Kleinigkeiten; ‘was — importance’, say ‘he showed also in more important matters’ (Angelegenheiten).

[12] and — nothing, und er erwarb sich seinen Ruf dadurch, daß er nichts für zu gering erachtete.

The great-grandsons of[2] those who had fought under William, and the great-grandsons of those who had fought under Harold, began to[3] draw near to each other in friendship, and the first pledge of their reconciliation was the[4] Great Charter, won[5] by their united exertions, and framed for their common benefit. Here commences the history of the English nation. The history of the preceding events[6] is the history of wrongs inflicted[7] and sustained by various tribes, which, indeed[8], all dwelt on English ground, but[9] which regarded each other with aversion such as[10] has scarcely ever existed between communities separated[11] by physical barriers.—Macaulay, History of England.

[1] Die ‘Magna Charta’ ist der am 19ᵗᵉⁿ Juni 1215 dem König Johann ohne Land abgerungene Staatsgrundvertrag, welcher als Grundlage der englischen Verfassung gilt.

[2] ‘of those — Harold’. These two clauses are best rendered in a contracted form, thus: ‘of the men who had fought under W. and H.’

[3] to draw near to each other, sich einander nähern; in friendship, freundschaftlich, adv.

[4] die Magna Charta.

[5] The two clauses containing the two p. ps. must be turned into one contracted relative clause, as explained in S. 7, N. 3, B. Use the verbs in the Impf. of the Passive Voice. To frame, entwerfen.

[6] Ereignis, n.

[7] The two p. ps. qualifying ‘wrongs’ (Unbilden) should be placed before that noun, as explained in S. 7, N. 3, A; of, von; to inflict, verüben; to sustain, erleiden; by — tribes, verschiedener Volksstämme.

[8] zwar; on = upon; ground = soil.

[9] but — aversion = but (jedoch) showed such an aversion against one another. The Article, when used in connection with adjectives and adverbs, stands in German generally before those words: such an aversion, einen solchen Widerwillen. Since the clause to be translated is in reality but a part of the preceding relative clause, which it completes, the verb must be placed?

[10] such as, wie, after which supply the pron. er, to give more distinctness to the rendering; to exist, bestehen; communities = nations.

[11] welche durch natürliche Grenzen von einander getrennt sind.

Mr.[1] Denham had been in business at Bristol, had failed[2], compounded, and gone[3] to America. There[4], by a close application to business as a merchant, he acquired a plentiful[5] fortune in a few years. Returned[6] to England, he invited his old creditors to an entertainment, at which he thanked them for the easy[7] terms (S. 16, N. 10) they had favoured[8] him with, and, though the guests had expected nothing but a good treat, every[9] man, at the first remove, found to his astonishment a cheque [15]under his plate for[10] the full amount of the unpaid remainder, with interest.—Dr. B. Franklin.

[1] ‘Mr. — Bristol’, translate ‘Mr. D. had had a business at (in) B.’, and place the object after the adverbial circumstance of place.

[2] to fail (in business) fallieren; to compound, accordieren. Verbs from the Latin with the termination ieren do not admit of the prefix or augment ge in the Past Participle, but follow in all other respects the weak or modern form of conjugation.

[3] Say ‘and was gone to America’. The verb gehen is always construed with sein, which auxiliary is especially used with Intransitive Verbs denoting a Passive State of the subject, a change from one State into another, or a Motion, if the place to which the motion is directed, or from which it proceeds, is either expressed or understood.

[4] The words ‘he acquired’ (erlangen) should, in an inverted form (App. § 14), follow the adverb ‘There’; ‘by — merchant’, durch unablässige kaufmännische Thätigkeit.

[5] plentiful = great. For the position of the object see App. § 9.

[6] Nach England zurückgekehrt; entertainment = meal; at which, wobei.

[7] bequem; terms, Bedingungen.

[8] to favour a person with something, einem etwas gewähren (v. tr.); nothing but, nur; treat, Schmaus, m.

[9] every — plate, fand doch ein jeder nach dem ersten Gange zu seinem Erstaunen unter dem Teller einen Wechsel vor.

[10] for — interest = which was issued (ausstellen) for (auf) the full amount of the remaining (rückständig) debt with (nebst) interest.

It seems to me, that[1] when the animalcules, which form the corals at the bottom[2] of the ocean, cease to live, their[3] structures adhere to each other, by virtue either of the glutinous remains within, or of some property in salt-water. The interstices being[4] gradually filled up with sand and[5] broken pieces of coral washed by the sea, which also adhere, a mass of rock is at length formed. Future[6] races of these animalcules erect their habitations upon the rising[7] bank, and[8] die, in their turn to elevate this monument of their wonderful labours.

[1] ‘that when the animalcules ... cease to live’. This clause may be briefly rendered by saying: ‘that after the death (Absterben, n.) of the animalcules’. To translate the last noun, form a diminutive of Tier.

[2] Meeresboden, m.

[3] ‘their — salt-water’. Use the following order of words for rendering this passage: ‘their little houses (dim. of Haus) either through the in them contained glutinous remains (Überreste) or through some (irgend eine) property of the salt-water held together are (Pres. of the Passive Voice)’.

[4] When the Present Participle is used to denote a logical cause from which we may draw an inference, it must, by the help of the conjunction ‘da’, be changed into a finite verb, i.e. one with a personal termination, thus:—

| The interstices being gradually filled up with sand, a mass of rock is at length formed. | Da nun die Zwischenräume allmählich mit Sand ausgefüllt werden, so wird aus dem Ganzen endlich eine Felsenmasse gebildet. |

The tense in which the verb is to be used, must always be determined by the context.

[5] and — sea, und mit vom Meere herangespülten zerbröckelten Korallen; it is a matter of course that the verbs must follow this passage.

[6] The following generations.

[7] ‘to rise’, here sich erheben. Present Participles used attributively are inflected like adjectives. Bank = reef.

[16]

[8] ‘and die — labours’, translate ‘and die to (S. 19, N. 7) contribute also in their turn (ihrerseits) to the elevation (Erhöhung, f.) of this monument of their admirable work (Arbeit, f.)’.

The[1] new bank is not long in being visited by sea-birds. Salt-plants[2] take root upon it (S. 4, N. 5, B), and[3] a soil is being formed. A cocoa-nut, or the[4] drupe of a pandanus is thrown on[5] shore. Land-birds visit it[6] and deposit the seeds of shrubs and trees. Every high tide, and still more[7] every gale, adds something to the bank. The[8] form of an island is gradually assumed, and last of all[9] comes man (S. 3, N. 2) to (S. 19, N. 7) take possession.—M. Flinders.

[1] The new coral-reef is (S. 2, N. 1) now soon visited by (von) sea-birds.

[2] Sea-plants; to take = to strike.

[3] und so bildet sich eine Erdschicht.

[4] die Frucht einer Panane. Die Panane (Pandanus) ist eine Art Palme und wird auch Pandang (m.) oder Palmnußbaum genannt.

[5] an, contracted with the def. art.

[6] it = the same, to agree with its antecedent ‘shore’; to deposit, zurück´lassen; seeds, Same, m., used in the sing.

[7] still more = especially; adds — bank, trägt etwas zur Vergrößerung des Riffs bei.

[8] The latter (dieses) gradually assumes (an´nehmen) the form of an island. The adv. ‘gradually’ may be made emphatic; see App. § 14.

[9] zuletzt; ‘to — possession’ = to take possession of the same.

A fox observed[2] some fowls at roost, and wished to[3] gain access to them by smooth speeches. “I have charming news[4] to tell you,” he[5] said. “The animals have concluded[6] an agreement of universal peace with one another. Come down and celebrate[7] with me this decree[8].” An old cock, who was well on his guard, looked[9] cautiously all around, and the fox, perceiving (S. 16, N. 4) this, inquired[10] the reason. “I was only observing[11] those two dogs which are coming this way[12],” replied the cock. Reynard prepared[13] to set off. “What[14],” cried the cock, “have not the animals concluded an agreement of universal peace?” “Yes,” returned the fox, “but those dogs (S. 5, N. 2) perhaps have not yet[15] heard of it (S. 4, N. 5, B).”—Anonymous.

[1] Der überlistete Reineke (or Reinhard).

[2] to observe = to see; at roost, auf ihrer Stange sitzen.

[3] to — speeches, durch glatte Worte ihrer habhaft zu werden.

[4] charming news = something pleasant. To render ‘you’ use the dat. of the persnl. pron. of the 2nd pers. pl. For the construction see App. § 7.

[5] The words indicating the speaker, after a quotation, must be rendered in an inverted form (see App. § 13).

[6] to conclude, ab´schließen, str. v. tr.; the agreement of universal peace, der allgemeine Friedensvertrag; to come down, herun´terkommen; supply the adv. also between the verb and the separable particle.

[7] feiern.

[8] Beschluß, m.

[9] to look all around, sich nach allen Seiten um´sehen.

[10] to inquire the reason, sich nach der Ursache erkundigen.

[17]

[11] I was observing = I observed (beobachten). Which are coming = which come. The English compound forms of the verb with the auxiliary and the present participle, and of the verb ‘to do’ with the infinitive (I do come = I come. I did come = I came), must be rendered by the corresponding simple forms.

[12] dieses Weges.

[13] sich zum Davonlaufen bereit machen.

[14] Wie.

[15] ‘not yet’, here noch nichts.

Heavy articles[2] were (S. 2, N. 1) in the time of Charles II generally conveyed from place to place by waggons[3]. The[4] expense of transmitting them was[5] enormous. From London to[6] Birmingham the charge was £7 a[7] ton, and from London to Exeter £12, which[8] is a third more than was afterwards charged[9] on turnpike-roads, and fifteen times more than is now demanded by[10] railway companies. Coal[11] was seen only in districts where it was produced[12], or[13] to which it could be carried by sea, and[14] was, indeed, always known in the South of England by the name of sea-coal.

[1] Die Beförderungsmittel zur Zeit Karls des Zweiten.

[2] objects.

[3] Lastwagen, which place after ‘generally’.

[4] ‘The — them’, may be briefly rendered by the compound noun ‘Die Transportkosten’. It may here be pointed out that the German language lends itself more easily than any other living language to the formation of compound expressions. Many advantages result from this adaptability of the language to express in one single term which, otherwise, would require a number of words; but the greatest of these advantages seems to me to lie in the power it gives us to avoid the too frequent use of the Genitive, a power which, if rightly wielded, will impart great vigour, conciseness, and elegance to the student’s style of writing.

[5] were extraordinary high (groß).

[6] nach; ‘charge’, here Fracht, f.; ‘to be’, here betragen; £7, sieben Pfund Sterling.

[7] The def. art. is used in stating the price of goods, when the English use the indef. art.; as—

| Dieser Kattun kostet fünfzig Pfennige die Elle. | This cotton is sixpence a yard. (10 pfennigs = 1⅕d.) |

[8] The pron. ‘which’ referring to a whole clause, and not to a particular word in that clause, should be rendered by the indef. rel. pron. was; as—

| She acted without thinking about the consequences, which was very wrong. | Sie handelte, ohne über die Folgen nachzudenken, was sehr unrecht war. |

[9] berechnen; turnpike-road, Chaussee, f.

[10] von, followed by the def. art.; to demand, beanspruchen.

[11] Steinkohlen, used in the pl. without the art. Use the active voice with man, S. 4, N. 4.

[12] gewinnen.

[13] or — sea, oder wohin sie verschifft werden konnten.

[14] Say ‘and it was (sie wurden) in the South of England therefore (daher auch) only called sea-coal (Schiffskohlen)’.

The rich[1] (S. 5, N. 2) commonly travelled in[2] their own iron carriages with at least four horses. A[3] coach and six is in our time never seen, [18]except as part of some procession. The frequent mention, therefore, of such equipages[4] in old books is likely to mislead us. We[5] attribute to magnificence what was really[6] the effect of[7] disagreeable necessity. People[8] in the time of Charles II travelled with six horses, because[9] with a smaller number there was danger of sticking[10] fast in the mire.—Abridged from Macaulay’s History of England.

[1] Adjectives used as nouns are declined as they would be if the noun, which is understood, were to follow them. They are always written with a capital initial.

[2] in ihren eigenen mit wenigstens vier Pferden bespannten eisernen Kutschen.

[3] ‘A — seen’. This clause must be construed thus: ‘Except (Außer) in processions a coach and six (eine sechsspännige Kutsche, see App. § 14) is now never seen’. Supply the words ‘bei uns’ before the p. p.

[4] Staatsfuhrwerke; therefore ... is likely to mislead us = can therefore easily mislead (irre führen) us. The object ‘us’ must be placed immediately after the copula ‘can’.

[5] Wir schreiben der Prachtliebe zu.

[6] really = in reality; ‘effect’, here = consequence.

[7] Say ‘of a’.

[8] One (S. 5, N. 2).

[9] because ... there was danger, weil man ... Gefahr lief; ‘small’, here gering.

[10] to stick fast, stecken bleiben. Use the Supine, for: When the English Gerund (i.e. the verbal in -ing) is governed by a noun, a verb, or an adjective, it is generally rendered by the Supine. Comp. S. 78, N. 14. Examples:

| He possesses the gift of speaking well. | Er besitzt die Gabe gut zu sprechen. |